And so the Hubble Space Telescope was launched 34 years ago today as a joint venture between NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration, USA) and ESA (European Space Agency,) and is still cranking out the classics, as seen here. Having a large telescope up above the atmosphere and able to make extremely long exposures has been a huge advancement in our knowledge of the universe (and physics,) and despite newer models like the James Webb Space Telescope, there’s still a lot that Hubble can tell us. But for now (mostly because I don’t want to write a long post at the moment,) we just have a couple of the better images that it’s produced – clicking on them will take you to the higher resolution versions. Above is the Bubble Nebula, NGC 7635, the visible interaction of an active young star within molecular gas excited by the stellar wind of the star itself.

By the way, I mentioned trying to spot the HST with the help of Stellarium, to no avail – apparently it is no longer listed among the many satellites that the program can plot, and I have no idea why not, since I’ve found it that way before. Heavens Above, however, gave me the current location, but it turns out that the HST is only rising above the horizon for my area during the day, so no go on that end. I did catch it one night a few years ago, however.

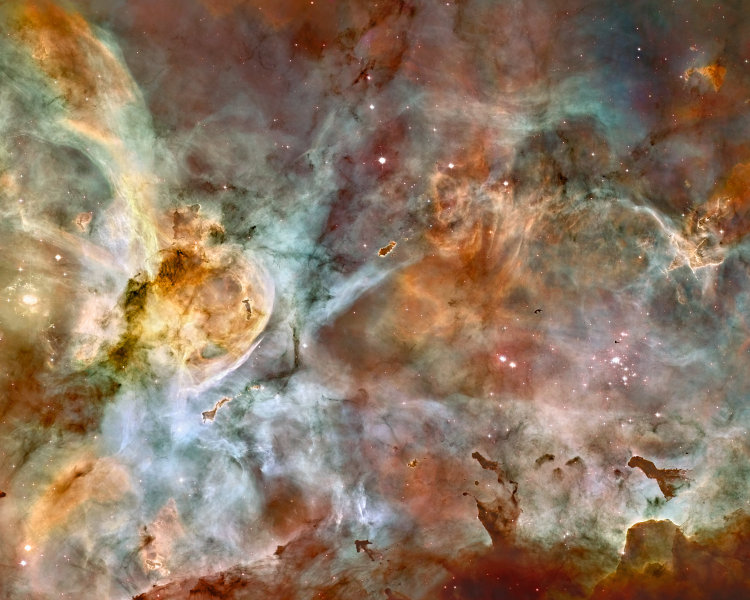

And this is the Carina Nebula, NGC 3372, a ridiculously complex region visible from the southern hemisphere. The caption gives a hint of this, but the digital cameras within the HST are all monochrome, only capturing levels of brightness. In front of them, however, can be inserted the filters of choice, occasionally for visual colors, but far more often for specific wavelengths of light that may be difficult or impossible for us to see directly. Multiple images are taken under different filters and composited later, usually with false, enhanced colors; the purpose isn’t to show the subject “as it is,” but to divulge information that isn’t readily apparent. This is far more useful to astronomy than dealing with just visible light wavelengths, but it does mean that no matter what telescope you buy, you won’t be reproducing these images or anything remotely like them (some of the wavelengths captured won’t even penetrate our atmosphere.) So while they’re pretty stunning, they’re not “true’ in most senses of the word – they’re actually far more informative. So there.

Pop on over to ESA’s Hubble site and poke around a bit – it’s pretty damn fascinating.