We didn’t have enough photos for November (for an arbitrary definition of ‘enough,’) so here are a few more – I already had most of them lined up in the folder for eventual use, but then settled on this topic and added a couple – even though they’re all only variants of the same image.

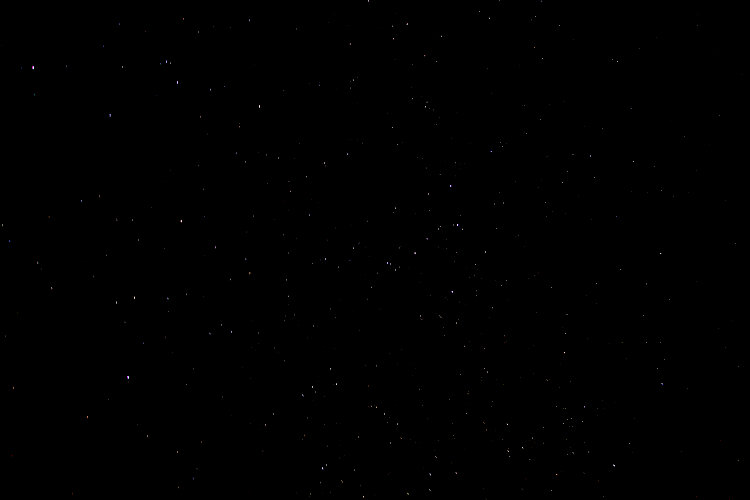

We start with a frame that I fired off while pursuing the Leonids and aurora borealis for the second time, not actually capturing either. But the view to the west yielded this:

What we have here is the faintest peek at the Milky Way running top to bottom just right of center. Not the time of year or night to capture a truly detailed image of it, since the galactic core is where all the great detail occurs and that’s well below the horizon. It was just barely visible to the naked eye if you looked carefully, brought out much better by a long exposure here.

Now, I say the Milky Way is visible here, but this is being a little disingenuous; we’re in the Milky Way, it’s our home galaxy, so every star you see here is part of it. We tend to associate it with the denser stars and dust lanes that are most visible on the ecliptic plane of the galaxy (which is the band we see here,) but technically, everything that you see here is ‘the Milky Way.’

Except – not quite.

First off, the long exposure brought up a lot of the fainter stars, so it’s difficult to tell what direction we’re looking because the brighter stars got ‘evened out’ with the dimmer ones. One of the current limitations of photography is the dynamic range, the difference between pure white and pure black and the fact that you can only get so bright, no matter what display you have – a picture of the sun on your monitor will never blind you like it would in real life. So the longer exposure that brings up those very faint stars that you can never see in real life will not let, oh, say, Cassiopeia, get beyond ‘white,’ so they appear much the same brightness and become lost in the mix. So I tweaked this image to look closer to what the naked eye view would be:

We’re a bit closer here, but again, dimmer stars were brightened by the long exposure, so Cassiopeia doesn’t stand out as distinctly as it does in person; I marked it:

Cassiopeia forms a nice lopsided ‘M’ in the sky and stands out well. Big deal, though, since it’s only five stars, right? And it certainly resembles a Greek queen, you have to admit. But Cassie serves a purpose, in that the stars form a pointer to something else, something that takes a bit of effort to see – it just barely intrudes into naked eye visibility in the best of conditions, and can be seen with binoculars as long as you can locate it, but we use the tallest peak of that ‘M’ as a pointer to find the Andromeda galaxy (M31,) which appears only as a speck here but is visible as a tiny cloud in the first image.

Andromeda, being another galaxy, is not part of the Milky Way and thus differentiates itself in terms of distances, being millions of times further away than anything else you see in that first image.

Except – not quite.

Out of curiosity, I brought up Stellarium and checked to see if any other galaxies were visible in that field of view, and there is one; it’s even ever-so-faintly visible in the image that I captured. It’s the Triangulum galaxy (M33,) actually only a little further away than Andromeda – ‘little’ being relative in astronomical terms, still about 186,000 light years further off or not quite twice the width of our own galaxy. That’s 2.538 Million light years distance for Andromeda versus 2.724 Mly for Triangulum.

Anyway, I marked them both for you:

And just so you don’t think I’ve trying to put one over on you, given that the Triangulum is hardly distinguishable at this resolution, we got in closer to the full resolution that the camera captured:

There they are in opposite corners of the frame here, that little smudge at upper left being right where the Triangulum galaxy would be, so I’m confident that’s what was captured. Now, of course, the star trails from the longer exposure (a full minute) are evident, also smearing the two galaxies but, to be honest, there really isn’t much to see from Triangulum anyway – it’s little more than a smudge until you get quite high magnification (i.e., decent telescope.)

To the best of my searching, those are the only two things that are not part of the Milky Way within this view, and while a close examination of the original frame yielded a few more blotches and hazes here and there, they’re all part of our home galaxy.

The funny thing is, everything was believed to be part of our home galaxy up until just a hundred years ago, when debates started over the spectrum and appearance of Andromeda/M31, settled by Edwin Hubble (yes, that Hubble) when he found a Cepheid variable star within Andromeda and determined that it was a hell of a lot farther away than the reaches of our own galaxy. Checking out both Edwin Hubble and Henrietta Swan Leavitt (who discovered the unique properties of Cepheid variables) is worth a read, certainly.