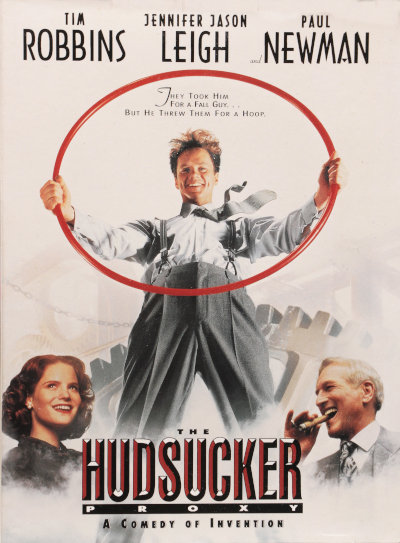

Despite being a Coen Brothers film, with writing and direction assistance by Sam Raimi, I’ve found very few people familiar with this one, and it’s a shame because this is a great little story on its own, even if it doesn’t quite measure up to the more popular films that they’ve made. This also came out in 1994, at roughly the same time as Forrest Gump, which naturally eclipsed most other films that year, yet they have some distinct similarities between them and, for my money, this one has a better story and is more charming than Forrest Gump, with better characters and performances by far.

The Hudsucker Proxy takes place in December 1958 in New York City, and bears the style and feel of the “rags to riches” films of that time period. Even better, it replicates many of the classic characters of the era, with no bad performances from anyone; Jennifer Jason Leigh as the fast-talking, streetwise journalist Amy Archer is simply fantastic, and listening to her rip off her dialogue (damn near monologues, most of the time) is delightful. Tim Robbins plays the lead as Norville Barnes, a naïve Muncieite newly arrived in the city and hoping that his new idea (“You know… for kids”) will propel him to success. Robbins has the face and voice for parts like this, but makes his transition to self-confident executive without quite leaving behind the naïvete, and he handles this adeptly. Paul Newman serves as the cynical and conniving Sidney J. Mussberger, the newly-appointed head of Hudsucker Industries who has to find a way for the board of directors to maintain controlling shares, and selects Barnes to fulfill this plot.

The Hudsucker Proxy takes place in December 1958 in New York City, and bears the style and feel of the “rags to riches” films of that time period. Even better, it replicates many of the classic characters of the era, with no bad performances from anyone; Jennifer Jason Leigh as the fast-talking, streetwise journalist Amy Archer is simply fantastic, and listening to her rip off her dialogue (damn near monologues, most of the time) is delightful. Tim Robbins plays the lead as Norville Barnes, a naïve Muncieite newly arrived in the city and hoping that his new idea (“You know… for kids”) will propel him to success. Robbins has the face and voice for parts like this, but makes his transition to self-confident executive without quite leaving behind the naïvete, and he handles this adeptly. Paul Newman serves as the cynical and conniving Sidney J. Mussberger, the newly-appointed head of Hudsucker Industries who has to find a way for the board of directors to maintain controlling shares, and selects Barnes to fulfill this plot.

Story-wise, the film is decent, though variations of such plotlines abound. It becomes quite surreal at times, and it’s easy to forget that the film opened with a narration, and by the end we’re reminded that this is being recounted by a character within, so the more unlikely aspects are perhaps a factor of overzealous storytelling. Visually however, the Coen Brothers have recreated the era supremely well, with a nod towards exaggeration to enhance the aspects, from the Brazil-like mailroom to the towering wall of filing drawers in the executive antechambers. Mussberger’s massive and empty office speaks of excess without purpose, or even comfort, while the newsroom where Archer works is the classic beehive of typewriters and cigar smoke. There’s even the spinning overlaid text gimmick to illustrate Barnes’ overwhelming disillusion while seeking employment, but the montage of the manufacturing process is so period-perfect, visually and musically, that it’s almost startling. Cinephiles (of which I am not) are likely to see homages to other films and directors within – some of them seem to jump out at times.

There are also little hints of the hands of Fate, evinced by the windblown newspaper page that dances down the sidewalk to embrace Barnes’ legs – masterfully staged, that – and the ‘dingus’ that rolls away to fall at the feet of a particular little boy (one that possesses a hell of a lot more talent than I myself had at that age, since I could never get them to work at all.)

The music cannot be ignored, since it is perfectly matched to the era as well as the plot and visuals – one could listen to the soundtrack (or simply the end credits pieces) and know, within a decade, what period the film is placed within. Moreover, some of the themes toy with us, suggesting certain songs while still being original works for the movie, so full credit to composer Carter Burwell.

Both The Hudsucker Proxy and Forrest Gump have their oblivious main characters successfully wending their way among those more savvy, though Barnes is simply naïve and not mentally challenged, and both have the characters responsible for real-world accomplishments, in Hudsucker to a lesser (and more believable) extent. The humor here is more apparent though, not wry tongue-in-cheek commentary but a lovely satire of both the 1950s and the films therein, as befits the Coen Brothers. It’s immersive while at the same time a send-up, and vaguely reminiscent of certain Looney Tunes cartoons from the same era.

Where the movie shines the brightest is the dialogue, however, and it’s handled better than anything that Tarantino has produced. Quite a few interchanges are relentless, never mugging for the humor but snapping in the next gag without respite, and the best among them is Leigh, effortlessly spouting three times the verbiage of an ordinary conversation as her no-nonsense journalist, while still masking a level of insecurity, her voice at times reminiscent of Judy Garland. Watching Robbin’s character cut through this façade, wholly unintentionally, is certainly fun. The best achievement, though, comes from their first meeting at a lunch counter, entirely and dramatically narrated by two cynical cab drivers observing from across the diner. This simple variation is far more effective than filming the interaction ‘straight’ and highlights the absurd nature of Archer’s machinations recounted through the patois of the boroughs.

The casting is also flawless, right down to the two-second character appearances, but without subtleties, dancing on the line between character and caricature (also a Coen Brothers trademark); within a line or two, you know all you need to know about just about everyone in the film. Is this heavy-handed, or an aspect of the story being recounted from memory? I’m not sure it matters at all, since we’re not here to solve a mystery or fathom some deeper insights, we’re just along for the ride – the film is about entertainment, not introspection. And this is where it departs radically from Forrest Gump, because we’re not going to contemplate Barnes’ life or how major events surrounded him, we’re just going to see where his glass ceiling lies.

Will the city mold or break Barnes? Will Archer gain what she needs with her big story? Will Mussberger thank his tailor? It’s worth the 111 minutes of your time, not necessarily to find out, but just to see it play through.