Courtesy of NASA’s Astronomy Photo of the Day, I present one of the most interesting examples of unintuitive physics: the curvature of spacetime to produce a gravitational lens. The ring that you see here is not the shock wave from a supernova affecting the surrounding gases, as I first thought, but actually a blue galaxy far beyond the yellow one in the center, whose image has been distorted into a surrounding ring because of the dense gravity of the central galaxy.

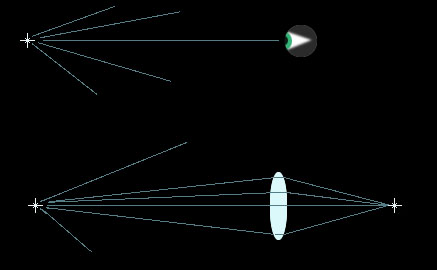

Here’s how it works. A normal lens, as almost anyone can tell you, “bends light,” but what this actually means is not as well understood, and often poorly illustrated. Let’s say you have a star, which only looks like a point of light from our distance (I added the twinkle for artistic statement.) It’s emitting light in all directions, so we can take a few paces to the left and still see it, or across the continent, or (should we be able to travel that far) all the way on the other side of it. The light from it is actually a spreading globe of photons, and we see just the one stream that meets our eyes (yes, that’s an eye in the upper part of the illustration.) A lens, however, catches all of the streams that meet its surface, essentially a cone, and bends the light to make all of these streams converge back down into the ‘dot’ of the star – provided that you’re the right distance for that particular lens, called the focal length.

Here’s how it works. A normal lens, as almost anyone can tell you, “bends light,” but what this actually means is not as well understood, and often poorly illustrated. Let’s say you have a star, which only looks like a point of light from our distance (I added the twinkle for artistic statement.) It’s emitting light in all directions, so we can take a few paces to the left and still see it, or across the continent, or (should we be able to travel that far) all the way on the other side of it. The light from it is actually a spreading globe of photons, and we see just the one stream that meets our eyes (yes, that’s an eye in the upper part of the illustration.) A lens, however, catches all of the streams that meet its surface, essentially a cone, and bends the light to make all of these streams converge back down into the ‘dot’ of the star – provided that you’re the right distance for that particular lens, called the focal length.

Gravity can be strong enough to bend light. This is not entirely true, since what it does is curve spacetime, which is what the light travels through – you can draw a straight line on a piece of paper and then curl the paper, curving the line. Close enough. With very large galaxies, or more often a whole cluster of tightly-packed galaxies, the gravity can be dense enough that the light from a distant star or another galaxy, out of our sight behind the first, is bent away from its original path that would normally have not even come near us, going instead to Proxima Centauri or someplace. If the alignment is just right, we can see multiple distant objects in several mirror positions around the lensing galaxy, as the light path is bent according to the strength of the gravity at certain points around the lensing galaxy. Placed exactly right, and with fairly high uniformity in gravity around the galaxy, and the distant hidden subject gets distorted into a surrounding ring, which is what we see here with yellow galaxy LRG 3-757. It obscures our direct line of sight to the distant blue galaxy, but we get a nearly spherical path from around the edges, as it were.

Gravity can be strong enough to bend light. This is not entirely true, since what it does is curve spacetime, which is what the light travels through – you can draw a straight line on a piece of paper and then curl the paper, curving the line. Close enough. With very large galaxies, or more often a whole cluster of tightly-packed galaxies, the gravity can be dense enough that the light from a distant star or another galaxy, out of our sight behind the first, is bent away from its original path that would normally have not even come near us, going instead to Proxima Centauri or someplace. If the alignment is just right, we can see multiple distant objects in several mirror positions around the lensing galaxy, as the light path is bent according to the strength of the gravity at certain points around the lensing galaxy. Placed exactly right, and with fairly high uniformity in gravity around the galaxy, and the distant hidden subject gets distorted into a surrounding ring, which is what we see here with yellow galaxy LRG 3-757. It obscures our direct line of sight to the distant blue galaxy, but we get a nearly spherical path from around the edges, as it were.

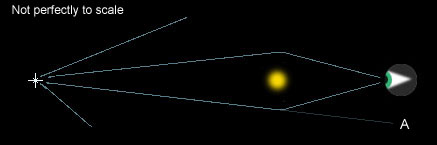

What’s interesting about gravitational lensing is, if we were along the line of one of those original paths from the distant star or galaxy, continuing an imaginary path unbent past the gravitational lens (see point A in the illustration,) we would have a perfectly clear line of sight to the distant subject and never see it, since the light was redirected. And in fact, we can only speculate how often this actually happens, since we have no way of knowing. Gravity distorts the path of all light, but usually in such small increments that it doesn’t matter much.

When Einstein proposed General Relativity, which indicated that gravity wasn’t an attractive property but rather an effect of spacetime itself, we didn’t have the ability to test it out in any way, but plenty of astrophysicists hashed out the details looking for errors or implications. One Fritz Zwicky extrapolated it to mean that areas of very high gravity, such as close-packed galaxy clusters, could bend the light paths from more distant objects. It’s simply fascinating to see theories of such a bizarre nature be proven with remarkable images such as this. Another curious implication of General Relativity is the collapsed neutron star usually called a black hole, which would also lens light that passed a certain distance away, but completely capture light that passed too close. We should be able to see lensing from such as well, except that, to our knowledge, black holes have only occurred in the centers of galaxies, and might even be necessary for galaxy formation. Thus it is entirely possible that the lensing galaxy you see in this image is home to a black hole deep in the center, but we do not see a ‘hole’ because it is surrounded by stars well outside of its event horizon, the imaginary sphere around it where light cannot escape. There is even a very very faint chance that some of the light in that central smudge is from stars on the opposite side of a central black hole, bent towards us by the gravity.

As lenses go, by the way, LRG 3-757 is a whopper. About 4.6 billion light years away at the time the light left, it’s one hell of a focal length. It’s also a tad heavy to carry around, as you might imagine, so not really useful to look at anything else. And as seen, its field curvature is kind of egregious.

Here’s another cool thing. The universe is expanding, and the light reaching us now is from objects that have long since left those positions. The distances between LRG 3-757 and the warped galaxy forming the ring are changing, and this curious optical affect will vanish after a while – probably well outside of our lifetimes. At the same time, others that we cannot see now may appear later on as the cosmic focal length changes.

Be sure to check the original APOD page and click on the image to see the high resolution version, which shows much more surrounding detail and is a nice starfield image on its own. And reduces the resemblance to HAL 9000. Once again, we have these images thanks to the Hubble Space Telescope, which is Photographer of the Decade (twice in a row) as far as I’m concerned. I’m gonna be frustrated when it’s decommissioned…

*

My thanks to Chris L. Peterson at Cloudbait Observatory for supplying a pertinent detail regarding LRG 3-757 on the Starship Asterisk forums, a great place to ask questions.

I am not a master of monochrome by any stretch, so this won’t be a definitive guide, but I can still provide some pointers. The first is that, more than with other approaches, your key factor is contrast. Actually, contrasting light levels, since colors can provide contrast too. Note that it doesn’t have to be high contrast, and in some cases, the gradual shading from light to dark, otherwise known as gradient tones, can look pretty good in monochrome.

I am not a master of monochrome by any stretch, so this won’t be a definitive guide, but I can still provide some pointers. The first is that, more than with other approaches, your key factor is contrast. Actually, contrasting light levels, since colors can provide contrast too. Note that it doesn’t have to be high contrast, and in some cases, the gradual shading from light to dark, otherwise known as gradient tones, can look pretty good in monochrome.

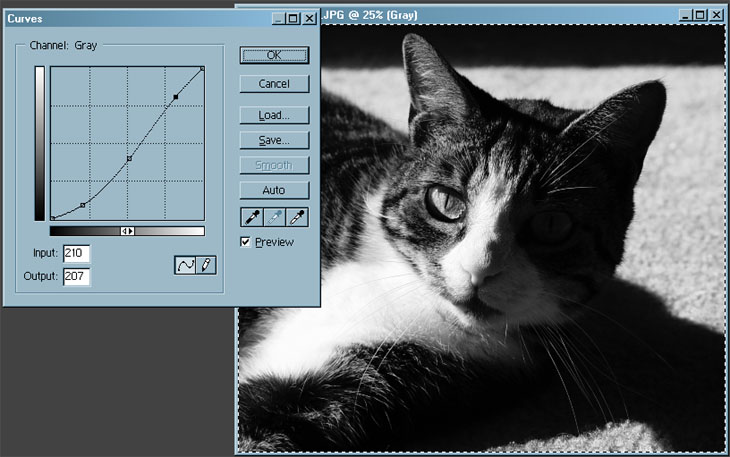

Another fun trick is channel clipping. Any digital color image is rendered into a channel for each color, in most cases Red, Green, and Blue (where those “RGB” references keep coming from) – or maybe even Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, and Black (CMYK – “B” was already taken by Blue who got there first.) You can open the Channels window in your editing program and click on each channel to see what the contrast levels are in that color register alone – sometimes this produces a much more interesting tonal shift than simply converting the image to greyscale. If you find one that you like, simply delete the other channels and keep the one, though you might have to convert this single channel alone into greyscale depending on your program. The right side of this image is each channel rendered into monochrome, illustrating how different each appears for the same photo. It might even help to convert into CMYK (if the original is RGB of course) and try channel clipping there to see if the effect is more to your liking. And of course, you can adjust the curves in the remaining channel as well.

Another fun trick is channel clipping. Any digital color image is rendered into a channel for each color, in most cases Red, Green, and Blue (where those “RGB” references keep coming from) – or maybe even Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, and Black (CMYK – “B” was already taken by Blue who got there first.) You can open the Channels window in your editing program and click on each channel to see what the contrast levels are in that color register alone – sometimes this produces a much more interesting tonal shift than simply converting the image to greyscale. If you find one that you like, simply delete the other channels and keep the one, though you might have to convert this single channel alone into greyscale depending on your program. The right side of this image is each channel rendered into monochrome, illustrating how different each appears for the same photo. It might even help to convert into CMYK (if the original is RGB of course) and try channel clipping there to see if the effect is more to your liking. And of course, you can adjust the curves in the remaining channel as well. The weather got nice today and I was doing some other photos outside, when the persistent buzzing finally got me to look up and see what was going on. It seems this European honeybee (Apis mellifera) thought our holiday lights looked rather appealing, and checked out numerous bulbs along the string before flying off.

The weather got nice today and I was doing some other photos outside, when the persistent buzzing finally got me to look up and see what was going on. It seems this European honeybee (Apis mellifera) thought our holiday lights looked rather appealing, and checked out numerous bulbs along the string before flying off. A few months back, I shot this Tolkienesque scene on the side of the river nearby, actually on the same outing that I chased down

A few months back, I shot this Tolkienesque scene on the side of the river nearby, actually on the same outing that I chased down