Star formation is a long-drawn-out process, which we know from both basic physics and actually seeing it happening in telescopic views, though we can’t see change in real time. Gases and dust have to be pretty thick in some region of space, molecular clouds to provide the raw materials, which gradually coalesce under combined gravity and with the help of Core-Collapse Supernovae (CCSN,) which are exploding, dying stars that send shock waves through these clouds and press the components closer together. We have images of regions like Orion’s Nebula and the Eagle Nebula, where we can see the emergence of new stars. This almost certainly happened with our own sun, once in the heart of a molecular cloud billions of years ago, but those raw components have since been either absorbed by various stars or blown away by the stellar winds once those same stars, ours included, reached their more powerful phases. It seems odd now, since we aren’t in anything like a cloud at all, nor are we even in a notable cluster of stars, but there’s been enough time for things to disperse under various influences.

In a post on Universe Today, they identified the first star believed to have formed at the same time as ours and from the same molecular cloud, a sister star to our own – actually, it’s been identified for a few years now but this is the first I’ve heard of it, mentioned in passing while the post dealt with the search for further siblings. That star is HD 162826 (or HIP 87382, or HR 6669, or SAO 47009, depending on what catalog system you prefer,) and it’s about 110 light years from us and shines at a magnitude of 6.5, right around the edge of unaided visibility in dark sky areas. It’s targeted here in a screen capture from Stellarium software:

You can see Vega down towards the bottom, and HD 162826 near the top in a string of three stars. This, naturally, made me wonder not only if it could be found without too much trouble when doing astronomical observations, but whether I had already captured an image of it while doing meteor shower images – the proximity to Vega meant I could possibly locate such images without a lot of searching.

It took two minutes.

This image is full-frame, taken during an attempt at the Eta Aquariids in May of last year, and Vega is that bright star about 1/4 down from the top and slightly left of center. We look at the top edge of the frame for our crucial bit. Yes, there’s a streak up there, but it’s only a satellite – what we want is delineated by two small red stripes. Let’s see it at full resolution.

Ignore the red and purple bits; I didn’t bother cleaning up the noise in this image, courtesy of the 6400 ISO necessary to snag fainter stars without motion blur – this is an 18-second exposure. Vega is now at the bottom of the frame like in the Stellarium plot, with HP 162826 at top, and it’s easy enough to plot the other stars nearby to know this is correct.

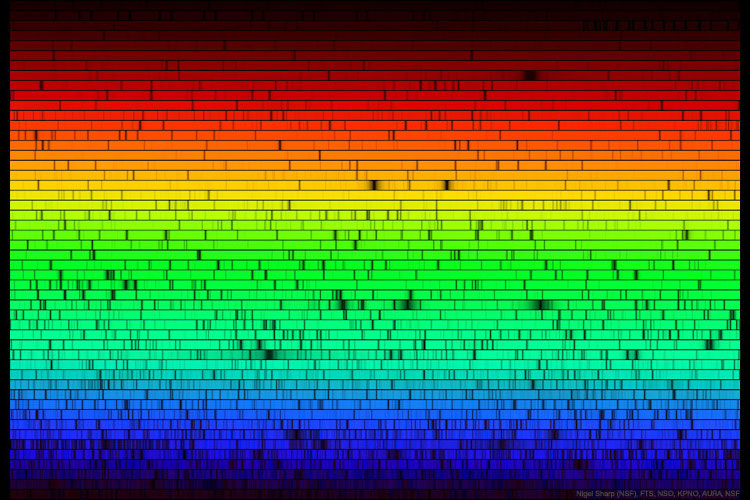

So, how do we know that HD 162826 is our sibling? Well, we don’t for sure, but the spectra is specific enough to give us (astronomers, anyway) significant confidence. The frequencies of light that stars emit tells of their composition, since different elements block different portions of the spectrum.

Image Credit: Nigel Sharp (NSF), FTS, NSO, KPNO, AURA, NSF

There are a couple of very rare and specific elements contained within our sun, and HD 162826 is the first to display these same elements. And while it’s 110 light years away, that’s close in stellar terms, and easily within the range of wandering possible in the 4.5 billion years since the birth of our sun, with all of the gravitational pulls of other stars nearby. At present, there is another candidate for sisterhood, HD 186302, but its orbit within the galaxy may throw some doubt on this. I checked, but I know I have no images of that one, because it’s within the skies of the southern hemisphere and invisible from any latitude that I’ve been in.

Next obvious question: Since HD 162826 likely emerged from the same molecular components as we did, is it among the potential candidates to harbor life? The answer apparently is that it’s a low chance – HD 162826 does not indicate the presence of any gas giants (determined by both changes in spectra and brightness when such a planet eclipses the star, and perturbations in the motion of the star itself,) and without such planets, the composition of the proto-planetary disc, from which the planets would form, is called into question. As mentioned above, the emergence of new stars and their stellar winds changes conditions within the molecular clouds, so it remains possible that our own sun, had it emerged earlier than HD 162826, eradicated the components that would have helped life form around its sister. Which sounds like typical sibling rivalry.

Some of these details, like much of astronomy, are speculative and subject to revision as we observe more closely, so who knows what we’ll have discovered in a mere ten years? Right now, I’m pleased that, immediately upon finding out that we have a sister (probably/maybe,) I can produce my own photo of her. But it’s probably not her best side.