Once I completed the previous book review, I dropped the authors a courtesy note to make them aware of it. This led to some correspondence, with the result that Matt Young, a professor of physics at the Colorado School of Mines and the author of several works, has offered a book review of his own. I am happy to host him as a guest reviewer, and while I have not yet read this book myself, I have more than a passing interest in the matter. In legal action regarding potential child pornography and abuse, the justification of “protecting the children” is frequently an emotional response, and may not take into consideration the traumatic and damaging nature of actions like protective custody, which can be invoked well before evidence is even presented. This has questionable merit for cases where guilt is well established, and is reprehensible when innocence prevails. Harming children (and adults) to save children, sometimes from absolutely nothing, is an action that requires critical examination.

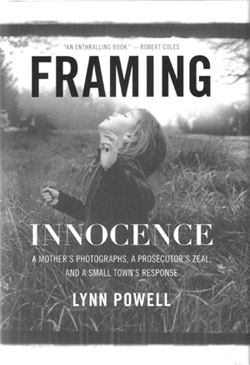

So herewith, Matt Young’s review of Framing Innocence: A Mother’s Photographs, a Prosecutor’s Zeal, and a Small Town’s Response by Lynn Powell:

This is a book that should never have been written, because it details a prosecution that should never have been brought. Very briefly, Cynthia Stewart took photographs of her 8-year-old daughter washing herself in the bathtub and was prosecuted for obscenity.

This is a book that should never have been written, because it details a prosecution that should never have been brought. Very briefly, Cynthia Stewart took photographs of her 8-year-old daughter washing herself in the bathtub and was prosecuted for obscenity.

I played a bit part in the drama — having inadvertently inspired the title of the chapter “Rorschach” — and I read the book not so much with interest as with growing consternation. For the first two-thirds or so, the book reads a bit like a novel, but then it unfortunately becomes anticlimactic, as you desperately want something dramatic to happen. Life is rarely like art, however, and the author was stuck with nasty facts. Very nasty facts.

The main character in the book is Cynthia Stewart, who is described as an aging hippie and who also appears both naïve and uncommonly stubborn (though some would call it principled). The best advice she got, which was unfortunately correct, was not to expect justice from justice system; she did not get it. Indeed, she and her family probably would have been bankrupted but for $40,000 in contributions.

The most interesting character in some ways is the guardian ad litem, the official appointed to look out for the interests of Stewart’s daughter. This woman looked for all the world like a right-wing anti-pornography crusading lunatic, but her commitment to truth and fairness far exceeded her anti-pornography zeal: she took one look at the photographs and pronounced them perfectly innocent. She did everything she could to protect not only Stewart’s daughter, but also Stewart herself.

The same cannot be said of the prosecutor, Greg White. White is somewhat difficult to get a handle on, partly because he refused to be interviewed for the book on what appeared to me to be a pretext. Nevertheless, he initiated a prosecution that the city attorney had declined and at least briefly subpoenaed an 8-year-old to testify against her mother. I thought at first that he had finally recognized that the prosecution was, at best, ill-advised but was too obstinate to back down. Later, though, he seemed genuinely bewildered that court-ordered counseling had not changed Stewart’s mind about the photographs. I do not know which was worse, but I came away with the feeling that the only perverts in this case were in the prosecutor’s office. White went on to become a US attorney and now is a federal magistrate.

I can think of several reasons why the photographs were not published in the book, some good, some bad. They were probably destroyed, but I do not recall the author actually saying so (and the book has no index, in my estimation, a cardinal sin for a nonfiction book). I think, however, that the reaction of the guardian ad litem and almost everyone who actually saw the photographs is convincing evidence that Stewart and her family were, well, framed by overzealous prosecutors. And, as the book details, she was by no means the only one. Let us hope this book provides an object lesson to all future zealots.

* * *

Once again, thanks to Matt Young for this guest review and the book image.