This morning’s bloom, because…

To thine own creepy self…

“So, Al,” you begin, (“you” meaning someone who reads this blog regularly, possibly an entirely fictitious character, and not necessarily you yourself, but thank you if it applies,) “are you trying to tell us that you spent all that time in Savannah, the edge of the subtropics, and did almost no insect photography? Seriously?” And to that I reply, “Well, my own area is such crap for landscapes and even sunset images, so I was wisely using the opportunity to fill out my stock in other areas.” So there. But I did indeed chase a couple of arthropodal subjects, including some detail shots of one I’ve had on my list for a short while now.

Long-jawed orb weavers (genus Tetragnatha) are a curious spider found most often – in my experience, anyway – on trees and reeds alongside water sources, but they also can be very fond of docks and boathouses. They have two outward appearances that are fairly distinctive, which is the pose at right when they’re out in their web over the water (you’re seeing a reflection of the sky in the water, since I’m aiming downwards,) or when threatened, they go to one of their web anchors and draw their legs into a straight line with their narrow bodies, blending into the thin leaves they live near. There are grassland varieties as well, but the aquatic-oriented species are the ones you’re most likely to see, and of course the one I captured here. There is a distinctive feature that they have, their namesake actually, which is only visible when you go in for close examination, and that’s the only warning that you get after the snarky way you opened the topic.

Long-jawed orb weavers (genus Tetragnatha) are a curious spider found most often – in my experience, anyway – on trees and reeds alongside water sources, but they also can be very fond of docks and boathouses. They have two outward appearances that are fairly distinctive, which is the pose at right when they’re out in their web over the water (you’re seeing a reflection of the sky in the water, since I’m aiming downwards,) or when threatened, they go to one of their web anchors and draw their legs into a straight line with their narrow bodies, blending into the thin leaves they live near. There are grassland varieties as well, but the aquatic-oriented species are the ones you’re most likely to see, and of course the one I captured here. There is a distinctive feature that they have, their namesake actually, which is only visible when you go in for close examination, and that’s the only warning that you get after the snarky way you opened the topic.

Here’s a slightly better look from the underside. The widest part of the body is their chelicerae, or fangs if you prefer, but it’s more than just the pointy bits that they stab poor unsuspecting mayflies with, since they’re jointed, manipulating digits. The thin little arms between the front legs are the pedipalps, their girth marking this specimen as a female. But of course I had to go closer, and in doing so, the spider spooked and ran up to the anchoring tree, positioning itself against the bark in camouflage mode.

Here’s the body shot, and no, night did not fall abruptly. I switched to full-on macro mode, which meant diffused flash unit, small aperture, and high shutter speed, and so the background was no longer bright enough to create its own exposure – especially in the early morning when I was doing these shots. Even as spiders go, Tetragnathas are not pretty examples, but you have to admit their abdominal coloration is interesting. And now you can start to get the impression of how disproportionate their chelicerae are – and also that their eye pattern, two rows of four each, is somewhat unnerving. It gives an idea of just how evolution has shaped us to react to certain details, because the eyes are way out of our comfort zone, preventing us from having the least little sympathy with such species.

Here’s a better look at those chelicerae, the best I managed – my model was shot in situ with only some nudges to try and achieve a better angle, so conditions were a bit limiting. They’re still sufficient to see that the chelicerae are these studded war clubs of appendages, two big cans of whupass with easy-open tops (no, I did not learn my writing style from Shakespeare or Dickens, why do you ask?) While I would like to offer some insight into why Tetragnathas require such huge canines, I’m afraid I’m at a total loss, since their food consists of flimsy slow water flies that certainly don’t seem hard to subdue – perhaps their venom is especially weak so they have to beat their prey to death. As you ponder this, take note of the coloration on the chelicerae and lower ‘face,’ in the image above, continuing the theme from the abdomen and indicating that the carpet does match the drapes (yeah, I’m in one of those moods.)

Here’s a better look at those chelicerae, the best I managed – my model was shot in situ with only some nudges to try and achieve a better angle, so conditions were a bit limiting. They’re still sufficient to see that the chelicerae are these studded war clubs of appendages, two big cans of whupass with easy-open tops (no, I did not learn my writing style from Shakespeare or Dickens, why do you ask?) While I would like to offer some insight into why Tetragnathas require such huge canines, I’m afraid I’m at a total loss, since their food consists of flimsy slow water flies that certainly don’t seem hard to subdue – perhaps their venom is especially weak so they have to beat their prey to death. As you ponder this, take note of the coloration on the chelicerae and lower ‘face,’ in the image above, continuing the theme from the abdomen and indicating that the carpet does match the drapes (yeah, I’m in one of those moods.)

I feel obligated to offer a little perspective, since these closeups may be provoking the wrong impression. Despite the daunting appearance of this species, my models were incredibly shy, as many spiders are, and getting this close took a fair amount of playing around since all the arachnid wanted was to hide. Even as I gently nudged her with a blade of grass, she timidly dodged aside, and eventually scampered off across the bark for a tighter crevice – I don’t think I could have induced a bite if I tried. Sound effects technicians, faced with having to try and find something appropriate for the menacing giant spider in any given horror sequence, resort to chittering, hisses, or even clattering (of the limb joints I guess,) but a more accurate expression would probably be a puppy whining.

I mentioned above something about how we react to eyes, and species like the one below (photographed at the side of the same pond) generate more sympathetic responses from people. Jumping spiders, however, are often fearless little cusses, rarely hesitating to walk across one’s hand or even jump onto the camera, and the easiest to get a portrait perspective on because they’ll actually turn to face whatever approaches. We find the other eyes easy to ignore and focus on those big two, and create a personality for them even when they have no more, and no less, that the Tetragnathas. Humans are weird.

Buried at the crossroads

I wish I could draw political-style cartoons, because then I’d open this with an illustration of an unkillable zombie, or maybe Jason from the Friday the 13th franchise, with the label “Free Will” on it…

This time around it’s an article in Slate from Roy F. Baumeister entitled, “Do You Really Have Free Will?” Baumeister is an ’eminent social psychologist,’ which may explain why he only approached the concept from the psychological angle. Unfortunately, that’s not really where the issue lies in the slightest, and in a way, this makes me glad I never got edumacated since now I can consider topics from angles other than my own narrow specialty.

It’s almost a rule that, when the title of an article asks a question, the answer the article will come to is, “no.” Baumeister, perhaps consciously, thwarts this by maintaining that yes, indeed you do have free will – but then again, it’s there in the subtitle: “Of course. Here’s how it evolved.” To support this, however, he chooses to define free will in his own way, and ignore all of the other points raised ad nauseum over the years. It’s a shame, because the article starts off promising enough:

It has become fashionable to say that people have no free will. Many scientists cannot imagine how the idea of free will could be reconciled with the laws of physics and chemistry. Brain researchers say that the brain is just a bunch of nerve cells that fire as a direct result of chemical and electrical events, with no room for free will. Others note that people are unaware of some causes of their behavior, such as unconscious cues or genetic predispositions, and extrapolate to suggest that all behavior may be caused that way, so that conscious choosing is an illusion.

Good – at least he’s aware of the many points raised, and the original article has links throughout this paragraph to send the reader in search of more info.

Yet, he addresses none of these, treating them as he hints at in the above paragraph as being from a narrow perspective, which he then perpetuates. He says,

Scientists take delight in (and advance their careers by) claiming to have disproved conventional wisdom,

but then,

These arguments leave untouched the meaning of free will that most people understand, which is consciously making choices about what to do in the absence of external coercion, and accepting responsibility for one’s actions.

Well, yes, that’s the conventional wisdom. The point is, physics operates in very predictable ways, and we are physical beings – the rather obvious conclusion is, we should be able (in theory) to predict what our decisions would be, and that means everything we do is determinable, and thus determined since the start of the universe. The “in theory” part is there because the amount of information necessary to do this is so vast we don’t have words to describe it, and it does recognize that there are probably laws of physics we don’t even know yet. Doesn’t matter – what we do know is working pretty damn well.

Naturally, this leads to the concept of determinism, or predestination if you prefer, and the simple extrapolation from there that we didn’t make the decisions, they were just a byproduct of the physics involved. Which then trashes Baumeister’s simple definition above. The coercion isn’t external, though, it’s internal. Is that what Baumeister is talking about, or isn’t it? Doesn’t matter – it’s what nearly everyone else is talking about, so if he is purposefully avoiding the subject in this manner, he isn’t actually addressing the topic.

Which is funny, because at times, he makes very pertinent points:

There is no need to insist that free will is some kind of magical violation of causality. Free will is just another kind of cause. The causal process by which a person decides whether to marry is simply different from the processes that cause balls to roll downhill, ice to melt in the hot sun, a magnet to attract nails, or a stock price to rise and fall.

Excellent! Yes, our brains are made up of physical matter, and what they do is based in physics. But then,

Different sciences discover different kinds of causes. Phillip Anderson, who won the Nobel Prize in physics, explained this beautifully several decades ago in a brief article titled “More is different.” Physics may be the most fundamental of the sciences, but as one moves up the ladder to chemistry, then biology, then physiology, then psychology, and on to economics and sociology—at each level, new kinds of causes enter the picture.

No. Wrong. In fact, horseshit. There are no different causes. What anyone is using in such cases are what are sometimes called emergent properties, or to be less pedantic, a collective process that just makes conversation easier. Stuff that we eat performs the same chemical energy exchanges as everything else in the universe, but because it occurs in a specific manner common to many species, we call it “digestion.” It is not a different cause – it is simply an easier and more specific term than, “exothermic reaction,” or even, “entropy.”

And therein lies much of the problem, because it is the very idea that there is another ’cause’ that sets off so much of the debate, from those trying desperately to support their idea of a soul or those who like the dualistic mind concept. Does Baumeister address these? No.

As Anderson explained, the things each science studies cannot be fully reduced to the lower levels, but they also cannot violate the lower levels. Our actions cannot break the laws of physics, but they can be influenced by things beyond gravity, friction, and electromagnetic charges. No number of facts about a carbon atom can explain life, let alone the meaning of your life. These causes operate at different levels of organization. Even if you could write a history of the Civil War purely in terms of muscle movements or nerve cell firings, that (very long and dull) book would completely miss the point of the war. Free will cannot violate the laws of physics or even neuroscience, but it invokes causes that go beyond them.

One of the many benefits of the scientific approach in the past century has been crossover – biology tying in firmly with chemistry, astronomy tying in irrefutably with atomic physics, and even psychology meshing in surprising ways with genetics (please don’t take that to imply, in any way, that psycho-social disorders are all genetic.) What we have found is that physics, deep down, combines them all. Baumeister implies above, perhaps only as misdirection, that physics applies only on the active level, muscles and nerves, and that the mind is something else. Like everyone that takes this stance, he never bothers to explain how this might be and where it occurs.

No number of facts about a carbon atom can explain life,

Well, yes, they can – mostly they tell us that our common definition of “life” doesn’t really apply very distinctly, and needs to be fudged for every application. An atomic chain reaction performs many of the same functions of life, in energy release and sustained reactions, as does fire. If we want it to mean replication of genetic material, viruses do that, but perform no energy exchanges on their own (they co-opt a host cell to for that function.) So, what definition of “life” is he referring to here?

…let alone the meaning of your life.

… annnd so casually, almost negligently, Baumeister introduces a philosophical angle without the faintest provocation. I’m game – what is the meaning of life, from free will, or the psychological angle, or indeed, any goddamn perspective you care to name? Baumeister doesn’t have it either – no one has given it a solid go, honestly – but apparently we are to believe it is a failing of all those vermin who deny free will when they cannot produce it. Tactics like this annoy the piss out of me, and it’s much worse from someone who isn’t grasping his topic very well.

As for physics explaining how the Civil War came about? You’d be surprised at how much it truly can tell us. DNA is a string of molecules bound by and replicated with mutual properties of attraction, the energy exchange of chemical bonds dictated by valences. These strings of molecules guide cells in protein development, which determines what kind of body traits develop, including ‘instinctual’ traits of the brain. Natural selection is a numbers game – whatever organism survives/reproduces best is able to spread its genetic heritage throughout a population faster than others. This gives rise to traits that tend to help the organism (and by extension species) survive. Among the traits that humans developed over their long history are fairness, cooperation, and functions that support tribal cohesion and produce negative reactions to being taken advantage of. At the same time, humans compete for limited resources, and preferred mating status, and optimal social standing. That pretty much describes economics in its entirety, not from a definition standpoint, but from an evolved behavior one – and economics (and fairness, and competition, and so on) pretty much explains the Civil War – in fact, most wars. The path might be very convoluted, and be broken up into distinctions such as ‘cell division’ or ‘proxy-based trade system,’ but it’s not as if physics isn’t involved on every level.

Baumeister is outright saying here that the path isn’t this clear, instead involving some special step therein that thwarts physics and gives rise to the special property of free will – even when admitting earlier that free will is part of the causality of physics. This seems to indicate that he hasn’t really thought the matter through all the way.

The evolution of free will began when living things began to make choices. The difference between plants and animals illustrates an important early step. Plants don’t change their location and don’t need brains to help them decide where to go. Animals do. Free will is an advanced form of the simple process of controlling oneself, called agency.

So, does the sunflower choose to follow the sun? Does the oak tree choose to split and lift the rock? If not, what are they using, and how does it differ from agency and free will? Biologists know that they do not, and that all such distinctions are merely arbitrary divisions in the spectra of living functions. We often create divisions for convenience, but this does not mean such divisions are truly distinctive and separable.

Decision-making is just the same. Faced with two or more choices, we have functions that compare the consequences to select what choice is most to our benefit, for whatever criteria seems to apply – and to assign importance to this choice, making us motivated to consider carefully rather than flippantly (most times, anyway.) This is the realm of emotions, the positive/negative feedback functions we have that we even see in other species to varying degrees (those that want to argue that dogs or mice, for instance, do not have emotions have to define what exactly emotions are first.) But are these different than the functions within a seed that make it sit dormant, in an envelope perhaps, until surrounded by water and nitrogen-rich soils? How does a seed ‘decide’ to sprout?

It doesn’t – ‘decide’ is misdirection. When the conditions are right it occurs. And much the same can be said for free will, which in most uses is the importance we feel in making a good decision. This importance is what makes us react when we’re told we don’t have it, but this is misunderstanding. The deterministic traits of physics also dictates the presence, and activity, of this importance within us. And Baumeister largely says this, but in tortured, ridiculously misleading ways.

Living things everywhere face two problems: survival and reproduction. All species have to solve those basic problems or else go extinct. Humankind has an unusual strategy for solving them: culture. We communicate, develop complex social systems, engage in trade, accumulate knowledge collectively, create giant social institutions (governments, hospitals, universities, corporations). These help us survive and reproduce, increasingly in comfortable and safe ways. These large systems have worked very well for us, if you measure success in the biological terms of survival and reproduction.

If culture is so successful, why don’t other species use it? They can’t — because they lack the psychological innate capabilities it requires. Our ancestors evolved the ability to act in the ways necessary for culture to succeed. Free will likely will be found right there — it’s what enables humans to control their actions in precisely the ways required to build and operate complex social systems.

Well, no – all that crap is simply anthropocentrism, the idea that humans are special. There are countless ‘cultures’ throughout the animal kingdom, if you bother to define it as common behavioral traits – canids have packs, birds have flocks, whales have pods, bees have hives, meerkats have communal child care, chimps practice adoption, and nothing destroys its environment like we do. Let’s not lose perspective.

All of that is evolved behavior. We can assign any portion thereof a fancy name if we like, but doing so doesn’t make it free from physical laws; we seem able to accept this easily when it comes to other species, just not for us. We’re different.

No, we’re not. Whether we like or dislike some fact of the universe doesn’t make it right or wrong, and the sooner we recognize this, the better. Right and wrong are also survival traits, in fact, part of that decision-making process. But they are also badly abused by misapplication. Decisions can be beneficial or detrimental; people are not right or wrong, and most especially, bare facts never are. They simply exist. However, the ill-feelings that people get when they believe that physics denies something that they consider to be important is responsible for all sorts of semantic jousting.

If you think of freedom as being able to do whatever you want, with no rules, you might be surprised to hear that free will is for following rules. Doing whatever you want is fully within the capability of any animal in the forest. Free will is for a far more advanced way of acting. It’s what a creature might need in order to adjust its behavior to novel situations, to get what it wants while still following the complicated rules of the society.

This is all just utter nonsense. The complicated rules of society are just the desires within us to act cooperatively rather than individually – just like hyenas and sardines. We’re getting so far off base now it’s frightening. From a cognitive psychology standpoint, this is a hopeless jumble of motivations. We have social tendencies because we worked better in groups than as individuals. We view decisions as important to accommodate the nature of choice – automatic reactions do not leave room for individual variation or changing conditions, so the ability to weigh consequences evolved. Many of our decisions are badly biased by group influences, as can be seen everywhere, while ‘free will’ is, as Baumeister describes it at least, a fiercely independent trait. But in reality they’re indistinguishable – our desire to ‘go with the flow’ will be treated internally just as important as our desire to think independently, because free will is the desire.

The vast majority of species that reproduce sexually select their mate from among many choices. Is this free will? You can call it that if you like, because we define such things arbitrarily just to make communication easier, but this in no way implies that it is a special property. Does the ability to select mates, or nest locations, or foods, make physics stop working as we know it? It’s a ludicrous question, isn’t it? Yet everyone who maintains that free will is a separate, special property is making exactly this argument. Regardless of how you might want to define it, there’s still an underlying set of laws, and these laws tell us, very distinctly and dependably, that energy behaves like this, all of the time, and matter will do this with the application of this much energy, all of the time. No linguistic two-step changes this in the slightest, regardless of how much anyone wants to draw imaginary lines around their favored domain.

But all of that is ignored in toto by Baumeister, which is a shame, because that’s where the debate lies. While he touches briefly on humans operating within physical laws without special properties, he somehow manages to avoid the consequences of this on the asinine concept of free will. And while touching lightly on evolutionary psychology, he nevertheless approaches the topic more from the dualistic brain/mind separation favored by too many philosophers and routinely dismissed by the majority of biologists.

And so, I’ll say it again. Determinism is highly probable – in fact, the only thing we have evidence of, like it or not (and if you don’t like it, at least try to find a good reason to deny it, rather than sophistry-laden philosophical arguments or the grave misunderstanding of quantum indeterminacy.) The functions within us, as determinable as they might be, also work to see that we are pleased with the act, or illusion if you prefer, of decision-making, and whether people eventually stop using the idiotic concept of free will or not will not ever change this. The universe might have a specific outcome, which we could see if we were omniscient, but we’re not, and we can treat life as a journey into the unknown as much as we do any coin toss (also, quite easily, determinable by physics,) any sports game, any movie we haven’t seen or person we haven’t met. While we dance among everything else in the rules dictated by atomic forces, what we experience and enjoy are the interactions we have and the bare fact that we don’t know what is to come. And that hasn’t changed.

Odd memories, part 11

Okay, this one’s just stupid, but that’s its charm.

Many years ago I worked at an extension of a humane society, a facility dedicated to dog training, wildlife rehab, and activities over and above the basic shelter services we provided – I was onsite caretaker and septic maintenance person (the Director felt it was easier and cheaper to train someone than to pay for monthly visits to examine the septic system – North Carolina has some righteous rules about wastewater.) One of the things added to the property was a small barn and corral, since we occasionally saw livestock and they’re kind of hard to house in a dog kennel.

Something that people never bothered to research, during their popularity in the nineties, was that Vietnamese potbellied pigs don’t stay small and cute, but get quite large as they get older. Come to think of it, they might not have been true Vietnamese potbellied pigs, just some breed bearing a resemblance when they were young that opportunistic breeders started selling, but whatever. The point is, we ended up with several over the course of a few years that ranged between 35 and 100 Kg (80-220 lbs.) As large adults, they were swaybacked, portly, bristly creatures whose eyes were sunk in the folds of the face, making them look like a political caricature of themselves. One in particular carried his dominance of the corral with a regal arrogance, accepting no lapse in obeisance from the others.

Then, we got a medium-small goat, and wanted to see if they would get along housed together, which would negate having to let them out in shifts. So one afternoon I set them loose simultaneously in the corral, with a hose and a pole ready, but remaining outside the fence to let them determine their own dynamic without my presence (this is more important than you might think – even domesticated animals behave differently when humans are about.)

The goat was completely cool with it all, as goats generally are – they’re mellow until things don’t go their way. The big pig, however, was very curious about this new resident, and wanted to ensure that it knew who ran the roost. He began puttering around the field in the general direction of the goat, making a string of little “buh” grunts as if playing with a toy boat – nothing overt, but conspicuously intruding on the goat’s space. The goat, accommodatingly, simply stepped aside to let the pig pass, which the pig took as encouragement – “it fears me!” Subtly increasing the volume and the speed of its grunts, the pig kept turning towards the goat every time it stepped aside, creating a humorous parody of a bullfight scored with asthmatic air compressor: “buh buh buh buh ¡olé! buh buh buh buh…”

The goat, having made the efforts to be Britishly polite, soon realized that this was not simply the blind meanderings of a self-absorbed porker, but an attempt to actually push the goat around, which was a perfidy that could not be allowed to continue. Almost negligently, the goat turned towards the pig, dropped his nose, and delivered a solid butt right smack in the center of the pigs broad, carunculated forehead.

“BUH!” exclaimed the pig, actually popping gently in the air backwards in utter shock. There’s a good chance he never saw it coming, with his eyes buried in flesh, but right there in front of him sat the goat, a mere one-third his own stately mass, svelte and dainty. Where else could it have originated? The goat, for his own part, watched for just a moment, satisfied that his message had been communicated, and dismissed the incident as inconsequential.

The pig pondered this. Obviously something had happened, but c’mon, he was pig! He ruled his land with an iron trotter. And the goat was this anorexic little thing, belly far from the ground and with eyes you could even tell the color of. Surely this was a mistake. So as the goat meandered off to look for vegetation or tin cans, the pig fired up the boiler again and started in the goat’s direction.

The goat, however, was no longer inclined to give the benefit of the doubt. As the grunts drew closer, he turned quickly and dropped his head again, but was still far from making contact.

“BUH!” repeated the pig with an even more frantic note, flinching from the threat yet untouched. No, there was no mistake; the goat was not going to brook any shenanigans from the pig, and had ways to make this memorable. Right there, the pig appeared to come to a decision: it would continue to rule the corral as Supreme Leader and Commander, but curiously it would never find any reason to have to enforce this with the goat.

And they remained that way, the goat doing as it pleased, and the pig pretending that the goat didn’t actually exist as it shouldered its way among the other pigs with great privilege. No worries.

Spectres and splattered bugs

We had plans to do the whole downtown Savannah thing again this trip, and spent one day and one evening down there. The Girlfriend wanted to do a walking ghost tour again, taking The Younger Sprog with her, but I decided to skip that and do a self-guided tour, starting with Colonial Park Cemetery.

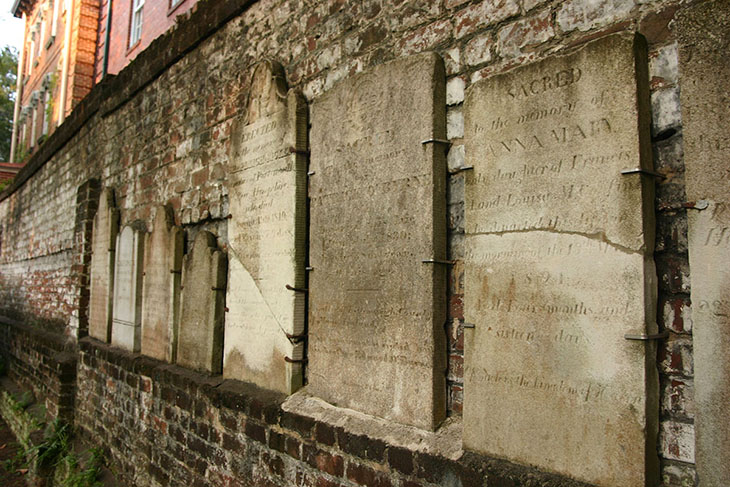

I’m not going to go into the whole history of the cemetery here – there are more than enough places to find it online – but I will say it’s a fairly classic old graveyard, nicely peppered with aged tombstones and twisted trees dressed in rags of moss, but it’s just a little too well-kept to fit the bill for really spooky images. Sunset was at seven-thirty and the gates closed at eight, so I had a small window of time to work with nice moody light, but it was limited. And there was no way I was going to chance getting locked into the most haunted place in America!

Okay, if you’ve read much else on this blog, you know I’m not too affected by that, and even if you want to get those feelings, the cemetery is in the center of town and far too busy for creepy chills. Most noticeable is that it seems, as the top image conveys, too empty to be very old. This is part of the history, since during the Civil War, occupying Union soldiers knocked down (and altered) countless headstones, so while the cemetery is full to capacity, a large percentage of the graves remain unmarked. Some of the markers were gathered up afterwards and affixed to the east wall, where they remain today.

I aimed for some artsy compositions and select vantages, playing with the conditions a bit, slightly hampered by my decision not to lug the tripod around – I just didn’t want the weight, and was glad I did so, because the evening was hot and humid and just the camera bag was taxing enough. But it did mean some of the things I attempted could have been much better with a firm support for the camera.

As the gates closed, I went to the darkest corner of the cemetery and purposely overrode the exposure meter to produce a dim, moody effect, bracing the camera against the bars of the iron fence. Regrettably, the lights therein were not the classic gas lamps visible in many other parts of the city, which would have done so much more for the effect, but I’m guessing the police want to see who’s trespassing in the cemetery after dark (I imagine it’s a common activity.)

After leaving Colonial Park, I wandered the streets a bit, looking for opportunities. A property posted with a “Consideration of Appropriateness” poster caught my eye, in too dim light to photograph. Since Savannah depends on its historic sections, any alterations to buildings within these areas is subject to committee approval – buildings must look as they did in colonial times, or as close as possible. As we found out on a later trolley tour, homeowners just outside of the border sometimes go for more flamboyant exterior colors, just because they can – an almost teenage defiance, though I imagine trying to operate a business in the historic district can be frustrating at times.

I eventually got down to the riverfront, the big draw of Savannah – classic buildings overlooking the slow river and usually forming the barricade along the two-story drop between city streets and docks.

I have to say I’m not too concerned with how a city looks, whether it’s historic or not, or whether the style is fashionable or whatever – it’s a city, and thus not very attractive to me. I did a few obligatory images, as much for the practice, braced against lampposts and atop walls – usually a few attempts, hoping to get at least one usable image without twitching the camera during exposures lasting as long as three seconds. I will say, at least, that Savannah has kept the tourist-trap, unbelievably schlocky stuff to a minimum – if you really need a sand dollar painted with glitter as a memento of your visit, it can be found, but you have to look for it. Restaurants, however, you can find easily.

Eventually I met up with The Girlfriend and The Younger Sprog, who’d enjoyed the ghost tour – a different one than last time (there are perhaps dozens of ghost tours available in Savannah.) Their guide was quite good, very animated, and they had decided I needed to see a couple of the buildings they’d gone past. Seen here, the Voodoo House, or its companion (I was getting the info secondhand and websearches on haunted houses in Savannah have given me a headache from facepalming) is one of many with its own sordid history, and of course during a ghost tour at night there’s plenty of atmosphere (that’s a joke, but you have to wait for it to develop.) The house sits back from the street and is completely shaded from streetlamps, rendering it almost totally invisible at night. Some of the people on the tour, taking flashlit images of the house with their digital cameras, had produced the “orb” effect so dear to the ghost chaser, and the guide had imparted some wisdom regarding what the details meant – The Girlfriend couldn’t remember exactly how it went, but it was something like, dust would produce solid orbs, uniform throughout, but those with more halo or edged effects were “something else.” Since The Girlfriend was using a DSLR, both with and without a shoe-mounted flash, I felt sure she wouldn’t be seeing any orbs through her camera, though it occurs to me as I type this that I never saw The Younger Sprog’s pics, taken with a little point-n-shoot – she may have been luckier. Glancing down, I saw the loose dirt in the crevices of the sidewalk was fairly laden with mica, so I scooped up a handful and instructed The Girlfriend to trip the shutter exactly when I told her, making sure the camera was using its little popup flash this time. I counted down and hurled the dust into the air in front of her camera just as she tripped the shutter…

Eventually I met up with The Girlfriend and The Younger Sprog, who’d enjoyed the ghost tour – a different one than last time (there are perhaps dozens of ghost tours available in Savannah.) Their guide was quite good, very animated, and they had decided I needed to see a couple of the buildings they’d gone past. Seen here, the Voodoo House, or its companion (I was getting the info secondhand and websearches on haunted houses in Savannah have given me a headache from facepalming) is one of many with its own sordid history, and of course during a ghost tour at night there’s plenty of atmosphere (that’s a joke, but you have to wait for it to develop.) The house sits back from the street and is completely shaded from streetlamps, rendering it almost totally invisible at night. Some of the people on the tour, taking flashlit images of the house with their digital cameras, had produced the “orb” effect so dear to the ghost chaser, and the guide had imparted some wisdom regarding what the details meant – The Girlfriend couldn’t remember exactly how it went, but it was something like, dust would produce solid orbs, uniform throughout, but those with more halo or edged effects were “something else.” Since The Girlfriend was using a DSLR, both with and without a shoe-mounted flash, I felt sure she wouldn’t be seeing any orbs through her camera, though it occurs to me as I type this that I never saw The Younger Sprog’s pics, taken with a little point-n-shoot – she may have been luckier. Glancing down, I saw the loose dirt in the crevices of the sidewalk was fairly laden with mica, so I scooped up a handful and instructed The Girlfriend to trip the shutter exactly when I told her, making sure the camera was using its little popup flash this time. I counted down and hurled the dust into the air in front of her camera just as she tripped the shutter…

If you wanted proof that Savannah is the most haunted city in America, there you have it – the little spooks inhabit every grain of sand. I’m sure if you look hard enough you can find whatever kind of shape or face you want – I myself see an owl monkey, and a Tusken Raider (it’s subtle, but the joke is in there.) This is, of course, a simple optical effect, the flash’s light bouncing from reflective objects too close to be in focus, made more distinctive by a dark background – in optical terms, these are ‘circles of confusion.’ I’ve personally done it with mist, corn starch, soap bubbles, and now with glittery sand, and it’s more pronounced when the camera flash is very close to the lens (when the flash is further out, the sand/dust/whatever directly in front of the lens doesn’t get any light, since it passes above, and by the time they’re far enough away to be in the strobe beam, they’re in focus enough to be a tiny speck that’s usually ignored.) Focusing further out helps the effect, too, since close objects are further out of focus. Those that captured orbs on the tour might have caught dust, humidity, and possibly even something the guide provided. So yeah, “atmosphere…”

If you wanted proof that Savannah is the most haunted city in America, there you have it – the little spooks inhabit every grain of sand. I’m sure if you look hard enough you can find whatever kind of shape or face you want – I myself see an owl monkey, and a Tusken Raider (it’s subtle, but the joke is in there.) This is, of course, a simple optical effect, the flash’s light bouncing from reflective objects too close to be in focus, made more distinctive by a dark background – in optical terms, these are ‘circles of confusion.’ I’ve personally done it with mist, corn starch, soap bubbles, and now with glittery sand, and it’s more pronounced when the camera flash is very close to the lens (when the flash is further out, the sand/dust/whatever directly in front of the lens doesn’t get any light, since it passes above, and by the time they’re far enough away to be in the strobe beam, they’re in focus enough to be a tiny speck that’s usually ignored.) Focusing further out helps the effect, too, since close objects are further out of focus. Those that captured orbs on the tour might have caught dust, humidity, and possibly even something the guide provided. So yeah, “atmosphere…”

Our trip coincided with the appearance of the lovebugs – no, not sassy little anthropomorphic VW Beetles, but a species of insect all too well known in the southeast, Plecia nearctica. A little smaller than fireflies, black with red ‘heads’ (actually their thorax,) at times of the year they swarm in vast numbers, mating while in flight, and one ends up driving through clouds of them. It was my duty to clean the windshield, which was necessary every time we refueled. At one point during the daylight tour of downtown, they were so thick they were clustered on the building walls, and we had them walking on us. They’re harmless, and clean off easier than many bugs, but the numbers have to be seen to be believed. As we started down the road one day, a mating pair on the windshield made a valiant effort to stay put; the female was eventually clinging desperately by one leg and vibrating madly in the wind, while the male, facing backwards, was nothing but a blur anchored by his genitalia. Impressive, but I walked gingerly in sympathy for a while after that.

I didn’t do many photos downtown during the day – been done to death, really. Meanwhile, where else are you going to go for images of slug sex? That’s right. Anyway, I’ll leave you with a big version of one of my favorites from the cemetery tour. There’s an instrumental from the Simple Minds album Street Fighting Years called, “When Spirits Rise,” and that’s what came to mind even as I was framing this. It’s faintly spookier in grayscale with the contrast boosted (isn’t everything?) but I like the color version best.

And if you look hard, you might see the ghost of Cousin It…

Simons and Solenopsis

Moreover, the admission costs and the variety of gifts available in the shop are all quite reasonably priced, and they provide tours and special activities like educational programs and turtle nest walks. Sea turtles lay their eggs on the eastern beaches of the American continents, mostly the warmer latitudes, where the hatchlings emerge on their own and make their perilous way to the water, to spend years swimming some really remarkable stretches of ocean before returning to the beaches to lay their own eggs. Dwindling numbers of sea turtles worldwide, no small part of it caused by humans, has prompted programs to try and protect the populations we now have, and conservation efforts include monitoring nests to prevent damage and depredation by scavengers.

Places like the Georgia Sea Turtle Center also rehabilitate turtles injured by fishing gear, boat propellers, shark attacks, parasitic infestations, and even ingesting those ubiquitous goddamned plastic bags (which they mistake for jellyfish.) Lil’ Simon, above, was named after Little St Simon’s Island where he was found, the sister of our next stop that day. The Center provides charts in the rehab area that list the details of the patients, solely for the visitor’s curiosity, and the staff is always happy to answer questions from the public. There are even large mirrors above the tanks for better views of the patients – the place is exceptionally well thought-out. And since so much of the staff in wildlife clinics are volunteers, always let them know how much you appreciate their efforts and drop a few dollars (or a lot of them) their way. It’s money a hell of a lot better spent than chasing the latest stupid phones or big screen TVs.

Places like the Georgia Sea Turtle Center also rehabilitate turtles injured by fishing gear, boat propellers, shark attacks, parasitic infestations, and even ingesting those ubiquitous goddamned plastic bags (which they mistake for jellyfish.) Lil’ Simon, above, was named after Little St Simon’s Island where he was found, the sister of our next stop that day. The Center provides charts in the rehab area that list the details of the patients, solely for the visitor’s curiosity, and the staff is always happy to answer questions from the public. There are even large mirrors above the tanks for better views of the patients – the place is exceptionally well thought-out. And since so much of the staff in wildlife clinics are volunteers, always let them know how much you appreciate their efforts and drop a few dollars (or a lot of them) their way. It’s money a hell of a lot better spent than chasing the latest stupid phones or big screen TVs.

Of course, while at the Center, I took the opportunity to chase a brown anole (Anolis sagrei) that was displaying pompously on a bench. I could probably be in a medical clean room and still find creepy-crawlies to photograph…

We headed north a short ways to St Simon’s Island, visible across the inlet from Jekyll, two of the many chunks of land separating the sea from the coastal wetlands that usually get the name “barrier islands.” There, we monkeyed around (seriously – I’m not showing you those pics) on a huge twisted old tree under the lighthouse, did a few portraits, and went for a swim in the inlet. I got some practice on my “block all the ugly unwanted details with foreground elements and cropping” techniques – the area surrounding the lighthouse was loaded with cars and signs – and I looked, once again in vain, for a decent place to do some snorkel explorations. We did the obligatory walk around the touristy areas of St Simon’s before heading back to Our Hosts’ Place outside of Savannah. Now, I probably could have amused myself for the week without leaving the property there, since they had a nearby pond with a lovely cypress swamp area, a beehive, and even some visitors (by now, you should know I’m not referring to humans with that.) They also had a Gator utility tractor that their dogs adored riding in, which we used for some exploring. The pond, alas, was too small to make an airboat viable – no southern swamps are complete without airboats.

We headed north a short ways to St Simon’s Island, visible across the inlet from Jekyll, two of the many chunks of land separating the sea from the coastal wetlands that usually get the name “barrier islands.” There, we monkeyed around (seriously – I’m not showing you those pics) on a huge twisted old tree under the lighthouse, did a few portraits, and went for a swim in the inlet. I got some practice on my “block all the ugly unwanted details with foreground elements and cropping” techniques – the area surrounding the lighthouse was loaded with cars and signs – and I looked, once again in vain, for a decent place to do some snorkel explorations. We did the obligatory walk around the touristy areas of St Simon’s before heading back to Our Hosts’ Place outside of Savannah. Now, I probably could have amused myself for the week without leaving the property there, since they had a nearby pond with a lovely cypress swamp area, a beehive, and even some visitors (by now, you should know I’m not referring to humans with that.) They also had a Gator utility tractor that their dogs adored riding in, which we used for some exploring. The pond, alas, was too small to make an airboat viable – no southern swamps are complete without airboats.

Unfortunately for me, what they also had, in great abundance, was fire ants. The red imported fire ant (Solenopsis invicta) is a particularly disreputable little shit that I am extremely well-accomplished in locating. I was diligent, this time around, in examining everyplace I walked for fire ant mounds, but this was a pointless exercise, since they simply had the run of the property and could be found everywhere without the faintest indication of their presence, at least until my feet began the familiar itching, burning sensation that heralds their displeasure at human presence. In summer I am either in sandals or barefoot, since my feet sweat profusely in anything more and even my sneakers become some kind of biohazard after a day. I was forced, eventually, to wear socks with my sandals, which horrifies the Fashion Police but no more than the oozing leprosy of my feet would have. Fire ants produce large, pus-laden or fluid-filled blisters, way out of proportion to their diminutive size, and the effects can last a ridiculously long time. Suffice to say I hate the little fuckers and am researching ways to hasten their extinction. I did make several attempts to photograph them in detail (managing not to get stung at those times, believe it or not,) but their movements are so rapid that I could not produce anything useful at all. Then I discovered that I had already gotten images of the same species dismantling a dead honeybee under the hive.

The honeybees, by comparison, were quite mellow and allowed a very close approach without taking the slightest issue, even during their busy times of the day. We were gifted some of Our Hosts’ honey harvest as well, fed by whatever wildflowers the bees had found nearby instead of the commercially-popular clover, and this lent it a buttery, faintly sharp flavor as if it had a hint of molasses – very nice! As a tiny bit of trivia about honey, it is a natural antibiotic and almost impervious to spoilage, and the Georgia Sea Turtle Center (among many other medical facilities) uses it to treat topical wounds since it coats well and doesn’t introduce contamination nor cause antibiotic resistance in bacterial strains.

Yet, there was a distinctive something that Our Hosts could not provide, something that no trip to the subtropics should lack, so we did a short trip to the Savannah National Wildlife Refuge to find… gators!

The Girlfriend’s Younger Sprog had never seen an American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) except in zoos, and that certainly doesn’t count, so we had to ensure that she saw one in the wild, and the Savannah National Wildlife Refuge is a pretty sure bet. Naturally, she had to show us all up by being the first to spot one, and the largest one at that – she had a rotten vantage point in the back seat on the grassland side of the drive instead of looking over the channel, and still found a beaut. Unfortunately, the height of the grass and decorum over approaching one weighing well over 90 kg (200 lbs) meant we have no really snazzy pics of that one, so what you see here is my meager find, whose head is as long as my blistered foot – just a leetle guy (it must be a male, since Our Female Host kept informing us that he was a Good Boy.) If you look close you can see minnows sharing the water alongside.

The Girlfriend’s Younger Sprog had never seen an American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) except in zoos, and that certainly doesn’t count, so we had to ensure that she saw one in the wild, and the Savannah National Wildlife Refuge is a pretty sure bet. Naturally, she had to show us all up by being the first to spot one, and the largest one at that – she had a rotten vantage point in the back seat on the grassland side of the drive instead of looking over the channel, and still found a beaut. Unfortunately, the height of the grass and decorum over approaching one weighing well over 90 kg (200 lbs) meant we have no really snazzy pics of that one, so what you see here is my meager find, whose head is as long as my blistered foot – just a leetle guy (it must be a male, since Our Female Host kept informing us that he was a Good Boy.) If you look close you can see minnows sharing the water alongside.

What was disturbing was that I spotted this one while the others had wandered elsewhere, did a few shots, and let it be, to find that it was gone when I returned with the others. However, it reappeared immediately and drifted right up to shore at my feet, obviously looking for a handout, which means assholes are going against all recommendations there and feeding the gators. Having alligators associate humans with food is quite obviously a bad idea, but too few people seem able to grasp positive reinforcement (or any kind of animal behavior,) which is one of the many reasons why I push critical thinking so much.

It should be noted that the Refuge’s Visitor Guide actually recommends letting a friend know where you had gone. Not just due to the alligators, but also because the trails are long, unshaded, lacking water, and bordered by swampland, mud, and open channels. People tend to think anyplace welcoming visitors is therefore safe, but this is true wetlands, which is challenging terrain to tackle unprepared. A car can handle the wildlife drive easily, but anyone hiking or bicycling should be prepared for demanding conditions.

And of course, alligators…

This one’s not as big as it looks – I just used a long lens – but I liked the effect overall. I saw the sun shining on that slit pupil and had to go for this composition. You did not miss the minnows here too, I’m sure.

And a last quick note, before I close this post to and start another, where we actually got into the city of Savannah. Upon getting back, The Girlfriend almost immediately left on another trip, returning just today. While away, she found something that reminded her irresistibly of me, and had to get them. What did she find, this love of mine?

Great.

Sun and Spanish moss

And so, slowly, I return to posting, revealing in the process that the last three posts were scheduled ahead of time to appear when they did, since we just spent a scant week in Savannah, Georgia with friends. We fit in most of what we’d aimed for; the primary exception, for me, was being unable to find any scorpions, something I’ve been longing to photograph for a while, and additionally motivated by the recent purchase of an ultra-violet flashlight. Scorpions fluoresce under UV, remarkably so, and I’ve been dying to capture this myself, but it was not to be this trip.

And so, slowly, I return to posting, revealing in the process that the last three posts were scheduled ahead of time to appear when they did, since we just spent a scant week in Savannah, Georgia with friends. We fit in most of what we’d aimed for; the primary exception, for me, was being unable to find any scorpions, something I’ve been longing to photograph for a while, and additionally motivated by the recent purchase of an ultra-violet flashlight. Scorpions fluoresce under UV, remarkably so, and I’ve been dying to capture this myself, but it was not to be this trip.

The Girlfriend and I drove down, accompanied this time by The Girlfriend’s Younger Sprog, who hadn’t been to Savannah before. The drive is about five-and-a-half hours road time, and our early start meant we arrived in time for lunch, before jumping back on the interstate again to drive another ninety minutes down to Jekyll Island. There were multiple motivations for this move; aside from Our Hosts only being free for the weekend, The Girlfriend was itching to return to the Georgia Sea Turtle Center, and I was itching to photograph sunset, at least, on the driftwood-strewn north beach. Since we’d arrived fairly late in the day by this point, I got to be satisfied first.

Before sunset, however, we had a few hours to poke around and see what could be found on the beach. I scared up a few tiny hermit crabs and a massive horseshoe crab for The Girlfriend’s Younger Sprog to photograph and she, in turn, located a feisty blue crab (Callinectes sapidus) in a shallow tidal pool for me. This one put on an amazing display of bravado, actually clapping its left and right pincers together audibly, and we soon discovered why this might have been (other than the bare fact that blue crabs are ridiculously aggressive little suckers): the crab was just beginning to molt its old shell.

I took up a position nearby, perched on a convenient piece of driftwood, and tried waiting out the process so I could have a complete photo sequence of this in optimum conditions, testing the patience (though they deny it) of Our Hosts, since I watched for over an hour. Seen above, the chitin has split along the rear and the crab is backing out, freeing first its hind limbs with the swimming flippers. The legs are drawn out in turn, and the pincers last, leaving the crab soft, pliable, and very vulnerable. However, this ended up taking so long, and I felt so guilty about making everyone wait for me, that I eventually gave up and rejoined the others for fluids and a snack (and bug spray,) before returning to the shore for sunset.

Now, there are two things that negatively affect sunset photography. The first, rather obviously, is overcast or stormy conditions. But the second is the polar opposite – skies that are too clear produce weak colors and no interesting cloud lighting or moody backgrounds. And unfortunately, the latter was what we had for our evening on Jekyll. While the light from the setting sun will go amber at least, seen here and in the opening image, to get the deep reds and purples that make for the groovy landscape shots takes significant humidity, and that just wasn’t present. I’ve said it before: nature photography takes a bit of luck in getting the right conditions – the skill part is knowing how to use them and being in the right place when they appear.

Now, there are two things that negatively affect sunset photography. The first, rather obviously, is overcast or stormy conditions. But the second is the polar opposite – skies that are too clear produce weak colors and no interesting cloud lighting or moody backgrounds. And unfortunately, the latter was what we had for our evening on Jekyll. While the light from the setting sun will go amber at least, seen here and in the opening image, to get the deep reds and purples that make for the groovy landscape shots takes significant humidity, and that just wasn’t present. I’ve said it before: nature photography takes a bit of luck in getting the right conditions – the skill part is knowing how to use them and being in the right place when they appear.

A small tip for the digital camera users: set the white balance to “sunlight,” especially avoiding the “auto white balance” setting, which tries to recognize color casts and shift them more towards neutral. You want the color cast – that’s what communicates ‘sunset.’ You can even enhance these by using the “open shade” or “overcast” settings (which compensate for the reduced yellows and reds of those conditions by adding them in within the camera,) and you can even use a colored card to set a custom white balance if you really want to be tricky. It’s easier to do this in post-processing, in an image editing program, but of course we’re now talking about significant digital enhancement. All I did here was use the “sunlight” white balance setting.

Perhaps the most-asked question from my photo students is about getting decent sunset images, because it’s actually a bit tricky. The camera’s exposure meter aims to produce middle-tones, a nice average light level, and has no idea where it’s aimed or what’s in the frame – it just reads light and adjusts exposure according to a simple idea: that most images are made up of middle tones. Aiming into the sun, naturally, is flooding the camera with light, and to produce a middle tone from this means darkening the image way below what we’re seeing with our eyes. This may enrich the colors of the sky, but render virtually everything else into a silhouette. Or if the exposure meter gets a reading from a foreground object (the shady side towards the camera,) it may produce an exposure for that and bleach the sky out entirely white. There are several ways to deal with this – exposure compensation, bracketing – but the easiest is knowing how to aim the key metering area in the viewfinder at something that will produce the light level you want and locking the exposure there with the Auto-exposure Lock button (marked “AEL,” or sometimes with just an asterisk) and then re-aiming the camera to frame the image the way you want it. While this is a tighter crop of a larger image, I locked exposure while aiming half onto the log, half onto the water under the sun, producing an exposure that left the sky a little darker but brought in some detail from the shady driftwood. It is one of several different exposures, the one I liked the best. I shifted to let just a fraction of the sun peek through the gap in the wood, and a small aperture was what produced the sunrays.

Perhaps the most-asked question from my photo students is about getting decent sunset images, because it’s actually a bit tricky. The camera’s exposure meter aims to produce middle-tones, a nice average light level, and has no idea where it’s aimed or what’s in the frame – it just reads light and adjusts exposure according to a simple idea: that most images are made up of middle tones. Aiming into the sun, naturally, is flooding the camera with light, and to produce a middle tone from this means darkening the image way below what we’re seeing with our eyes. This may enrich the colors of the sky, but render virtually everything else into a silhouette. Or if the exposure meter gets a reading from a foreground object (the shady side towards the camera,) it may produce an exposure for that and bleach the sky out entirely white. There are several ways to deal with this – exposure compensation, bracketing – but the easiest is knowing how to aim the key metering area in the viewfinder at something that will produce the light level you want and locking the exposure there with the Auto-exposure Lock button (marked “AEL,” or sometimes with just an asterisk) and then re-aiming the camera to frame the image the way you want it. While this is a tighter crop of a larger image, I locked exposure while aiming half onto the log, half onto the water under the sun, producing an exposure that left the sky a little darker but brought in some detail from the shady driftwood. It is one of several different exposures, the one I liked the best. I shifted to let just a fraction of the sun peek through the gap in the wood, and a small aperture was what produced the sunrays.

And then, I made a small mistake: I let Our Hosts book our suite without asking them where, exactly, we were staying. There wasn’t anything wrong in the slightest with our room – quite the contrary – but it meant I made no plans to be up at sunrise to chase more images, unaware that we were a short walk from the east shore of the island and ideally positioned for such pursuits. I woke early anyway, but didn’t venture out until the sky was fully light, to discover the beach so close. It meant that the light was much fiercer than preferred (again, pretty clear conditions,) but I still chased a few images anyway, joined a little later on by The Girlfriend and Our Female Host. There was some delay caused by camera lenses that had been sitting in air-conditioning overnight and were thus cool enough to attract condensation from the warm sea air, requiring several minutes to warm up and get clear. While you can wipe condensation away, it’ll return immediately until the glass temperature is right, and for dog’s sake don’t switch lenses in these conditions; condensation on inner surfaces, especially in a zoom or on the camera mirror, can take forever to clear. But while waiting, I used the fog as a soft-focus effect and tried a few shots anyway, with halfway-decent results. I admit to tweaking contrast slightly higher for the image at right.

And then, I made a small mistake: I let Our Hosts book our suite without asking them where, exactly, we were staying. There wasn’t anything wrong in the slightest with our room – quite the contrary – but it meant I made no plans to be up at sunrise to chase more images, unaware that we were a short walk from the east shore of the island and ideally positioned for such pursuits. I woke early anyway, but didn’t venture out until the sky was fully light, to discover the beach so close. It meant that the light was much fiercer than preferred (again, pretty clear conditions,) but I still chased a few images anyway, joined a little later on by The Girlfriend and Our Female Host. There was some delay caused by camera lenses that had been sitting in air-conditioning overnight and were thus cool enough to attract condensation from the warm sea air, requiring several minutes to warm up and get clear. While you can wipe condensation away, it’ll return immediately until the glass temperature is right, and for dog’s sake don’t switch lenses in these conditions; condensation on inner surfaces, especially in a zoom or on the camera mirror, can take forever to clear. But while waiting, I used the fog as a soft-focus effect and tried a few shots anyway, with halfway-decent results. I admit to tweaking contrast slightly higher for the image at right.

Just a short while later, I got a small break: a few spare clouds on the horizon blocked the sun for a minute, allowing some landscape shots with no glare and some interest above the horizon. I’m pleased with the steely appearance of the water, but did not get lucky enough to have a boat or some birds available when the sun was hidden. Next time, next time…

Of course, immediately after breakfast, we headed over to the Sea Turtle Center where The Girlfriend obtained even more stuff to decorate the car, but more on that in a later post. Right now, we’ll backtrack briefly to the sunset again, because of a curious thing I’d inadvertently captured. Below, one of the shots that included the fishing pier off the north shore, again cropped from a wider image.

And to the right, an inset of the same image, contrast enhanced slightly. While The Girlfriend and I were shooting down amongst the driftwood, it seems Our Hosts and The Girlfriend’s Younger Sprog were trying to attract our attention from the pier – you can just make our Our Female Host waving. I hadn’t the faintest idea they were there, being only millimeters tall in the wide-angle lens I was using, and only discovered this a few days later when they asked if we’d seen them and I happened to check the images closely. Sorry about that, guys – I would have framed you against the sun had I known.

And to the right, an inset of the same image, contrast enhanced slightly. While The Girlfriend and I were shooting down amongst the driftwood, it seems Our Hosts and The Girlfriend’s Younger Sprog were trying to attract our attention from the pier – you can just make our Our Female Host waving. I hadn’t the faintest idea they were there, being only millimeters tall in the wide-angle lens I was using, and only discovered this a few days later when they asked if we’d seen them and I happened to check the images closely. Sorry about that, guys – I would have framed you against the sun had I known.

Not your typical view

This isn’t something that’s ever come up before here, but I’m a little bit of an aviation enthusiast, especially World War II. The air war in Europe and the Pacific was a unique period in history, in a niche that combined powerful aircraft with personal combat, something not seen with the slow, flimsy craft of WWI, and that vanished in the jet age. There’s also something special about the engines of that time – throaty, deep-voiced piston monsters. I remember long ago in central New York, hearing the bass growl of four rotary bomber engines approaching and watching a Consolidated B-24 Liberator passing overhead – there’s simply no other sound like it, not even close. Years later on, I found out too late that there was a small fly-in taking place in the airport behind where I worked, unable to take any time off to visit it. A fellow enthusiast and I stood in the parking lot after work and listened to a North American P-51 Mustang take off and fade into the distance, disappointed that it didn’t even fly out on the runway near our end. We didn’t know that the pilot had circled around for a close pass until just before the plane reappeared at less than 500 feet and better than 300 knots, hurtling down the flight line at a velocity that put everything else out of that airport to shame, emitting a howl that could be felt in your chest.

Anyway, the video. Someone talked a crewmember of the Collings Foundation into attaching a GoPro video camera to the end of a gun barrel on the retractable belly turret of this (only flying) B-24J, and produced a fascinating perspective of this aircraft in operation.

The first noticeable bit is that the wind noise unfortunately overrides the marvelous sound of those engines. The second thing is the impression of being a rickety crate that comes from watching the vibration and flexing of the fuselage – except that it’s not the fuselage that’s moving, but the gun turret to which the camera is attached. It’s not surprising (or bad) that the turret has some play, because it has to traverse a wide field of fire and is supported by a single hydraulic column rising vertically in the center of the aircraft.

There are some details I’d like to draw attention to in the video. I’m not sure why the camera was mounted facing towards the turret rather than in the direction the guns faced, but it allowed us to see things like the cartridge chute underneath the barrel for ejecting the empty bullet casings, and the pair of dice suspended inside the ball turret (showing snake eyes.) The gun barrels themselves are shrouded in heat dissipating sheaths; .50 caliber (12.7mm) machine guns generate ridiculous amounts of heat, enough to warp the barrels with sustained firing, so the outer layer, connected to the barrel at numerous points, was intended to absorb heat away from the barrels and give it greater surface area to dissipate into the slipstream – this is much the same way a car’s radiator or the heatsink of a computer works. The holes simply increase airflow and thus energy transfer. Visible throughout the video is a bar extending from the belly of the aircraft just aft of the turret position – this is a bumper to prevent striking the tail during a nose-high landing.

At 5:38, watch the main glass in the turret to see the chase plane come into view – it appears multiple times in the video, and I think it’s the Foundation’s North American B-25J Mitchell. At 8:25, the bomb bay doors open; the B-24 was the only bomber with rolling “garage doors.”

As the turret traverses, you can sometimes see one of the waist guns projecting from the sides of the fuselage, closer to the tail – the J model carried ten .50 caliber machine guns for protection, which gives a faint indication of the demands of the European theater. Throughout most of the war, the Allied Air Forces had to operate almost entirely out of England, crossing the channel and usually a significant amount of the continent before reaching any bombing target. The bombers had the fuel load to accomplish this – the escort fighters generally did not. For much of the war, the bombers would have fighter escorts as protection for only part of their journey, but long before reaching the target the fighters would have to turn back through lack of fuel, so the bombers usually went unprotected into the most dangerous areas, where Axis fighters were thickest and closest to their own supporting airbases. While they had gun emplacements all around the aircraft, they couldn’t maneuver much at all when stacked into bombing formation, and wouldn’t have been a match for the agility of the Messerschmitt and Focke Wolf fighters anyway. Tracking an attacking fighter from a gun emplacement, accurately enough to do sufficient damage, was exponentially harder than maneuvering a fighter to nail the larger, slower, and predictable bombers, and countless bombers were lost under the onslaught despite the number of protective guns. And this says nothing of the anti-aircraft rounds, “flak,” that were fired from ground emplacements scattered thickly around likely targets.

Now, a note in general about restored WWII aircraft. Almost all of the ones you might find anyplace today never saw combat, for the simple reason that those that did were never shipped back to the states – that was an unnecessary expense in the wake of everything else post-war. In fact, the large majority of aircraft were scrapped, especially if they’d seen battle damage – the risk of airframe or component failure is sometimes accepted in wartime, but unwarranted in peacetime. Most of the restored aircraft in this country are ones that never got shipped overseas, being models not fitted for combat or that sustained damage before posting, and very often pieced together from multiple aircraft, whatever can be found.

The Collings Foundation’s B-24J is an exception, having served as a bomber and transport in the European theater before being transferred to the Indian Air Force, where it was retired in 1968. In 1981, a British aircraft collector found the airframe and paid to have it shipped to England, and then sold it to the Collings Foundation which paid to have it shipped to the States – as you might imagine, this was an expensive prospect, as was restoring the aircraft to flying condition. Parts are hard to find and often have to be machined by hand, and even original mechanical drawings are scarce – technology had moved on and no one saw any need to keep obsolete documentation. Restorations are usually by non-profit organizations staffed by volunteers, and funded by the public appearances.

So if you get the chance to see one of these birds up close, don’t balk at the costs – one day these will only be dusty museum pieces.

I’m not going to embed another video in the post, but go here if you want to see the startup and takeoff of three of the Collings Foundations aircraft, including the B-24J in the above video (second one that appears.) It’ll give a good idea of the sounds they make, though you’ll have to wait until the takeoff at the end. You’ll also see the difference in the nose configuration between the A and J models, and just why the belly turret had to be retractable. Or you can take a tour with Jay Leno through the interior of the B-17, very similar in layout to the B-24.

Don’t take it personally

It’s funny; I first read the posts which prompted this over a week ago, and have been thinking about this ever since.

To set the scene as briefly as I can, the first post can be found here, which details some highly questionable practices from a particular nature photographer, but admits that this is not isolated. The post covers everything from posed subjects to animal abuse, but the critical-thinker in me interrupts with a reminder of the distinction between “evidenced” and “inferred” – a few too many accusations in that post aren’t substantiated very well.

Now, just that single sentence in itself is enough to send too many people off into the accusation that I’m making excuses for the photographer, or think he was doing nothing wrong, or any variation of trying desperately to cram the whole issue into just two bins, “approve” or “disapprove” – this is partisan thinking, as if there are only two choices. However, that sentence means nothing more than exactly what it says; I issue this as a helpful guideline, because if anyone can’t understand that distinction or count higher than two, this post is going to be way over their head (Sesame Street is probably way over their head.)

The first post then linked to this “must-read” from Nicky Bay, a seriously accomplished photographer himself. Bay gives a detailed description of the proper ethical approach for nature photographers – or at least, his own take on it. Because the bare truth is, the term ‘nature photographer’ really only means ‘someone who takes mostly nature photos,’ and implies no particular approach, goal, education, ideology, or anything else. Everyone has their own preferences, and their own reasons for having them. For instance, Bay frowns on any kind of studio shot, and any kind of interference, up to and including getting leaves out of the way – he cites the negative impact he created once when doing so.

However, it’s not hard to find numerous nature photographers who not only violate these, they have good, rational reasons to do so (though the definition of rational is, naturally, a bit subjective.) More interesting though, is what you find when you start to examine the issue in detail. There is, quite distinctly, no such thing as “zero impact” – everything that humans do has some affect on their surroundings. While Bay may not wish to disturb a leaf because of his personal experience, I think it’s safe to say that he did not obtain his equipment by picking it up from under the Nikon tree where it fell naturally, nor does he live in a cave and use the all-natural internet. Walking up to his photo subjects undoubtedly wiped out thousands of tiny critters, as does simply going down to get the mail, to say nothing of hurtling through space in a car or airplane. I don’t want to pick on Bay here, since I’ve seen ethical guidelines from numerous different photographers, I’m just using his as an example.

I could point out that humans are not an unnatural species on this planet, having evolved with everything else, so the distinction of natural doesn’t have a viable meaning. I could point out that the leaves he purposefully avoids disturbing are continually eaten by herbivores or dislodged by storms. Both of those indicate that quantifying ‘impact’ in either a negative or positive manner requires a purposefully narrow perspective. I could also let this whole idea delve into trying to define avoidable and unavoidable impact, but that’s an unending argument, and one that moreover misses the crux of the matter. This crux is missed by damn near everybody, which is funny, because it comes from the very word that everyone uses blithely and assumes has a good definition: “ethical.” This stumbling block is always present, and nearly always ignored, often by people that should know better.

So, let me ask this: What does ethical mean, or if it’s easier, what is the goal of ethical behavior? If someone says, “We shouldn’t harm other species,” the first thing I’d point out is that this is manifestly impossible. Then I’d ask why we think our species should have special rules that other species don’t have, since the predator/prey thing, as well as the host/parasite concept, is everywhere we look. I’d also start messing about with the obvious history of mankind as an omnivore, and ask what makes this new ‘no harm’ rule functional?

It doesn’t take much to realize that ethical is defined solely by personal opinion, but it takes a little more thought to recognize that it’s a bare emotion masquerading as a discrete concept – while anyone can create a rationalization of it, you’d be hard-pressed to find even a broad consensus of what it means, or should mean. And even that ‘should’ part is loaded, because who or what makes us think anything should be, as opposed to simply seeing what is?