So here’s a compositional aspect that I admit I have to remind myself of far too often: purpose. No, not the abstract concept that might be illustrated by someone striding determinedly with a clipboard in their hand, but the purpose of the image itself – what do you want to do with it?

For instance, I’ve already made it clear that I don’t really do ‘art,’ and instead try for illustration or interest. But, depending on your approach to photography (most especially, whether or not you intend to make any money from it,) it may serve you well to consider how many different purposes any image or subject can serve. It is just this aspect that is often addressed by specific photographic genres, like portraiture or journalism or abstraction, each requiring a different approach to the same subject. It can be very useful to consider multiple purposes when you have a particular subject handy, especially if it’s a rare or difficult subject. It can also do a lot for your employment opportunities, by giving you experience in different approaches rather than fixing you within a particular category.

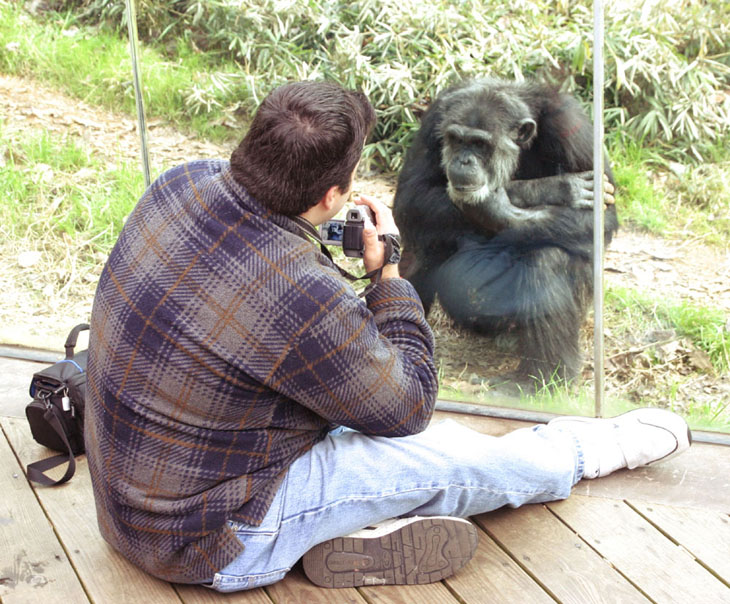

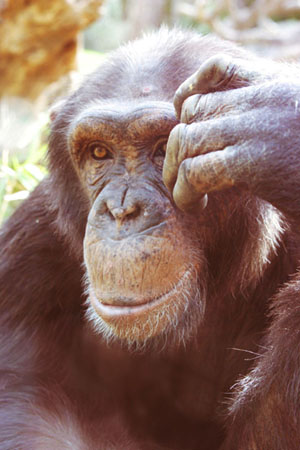

When traveling, most people like to get their traveling companions in the frame with something that speaks of their location, which is great – but if it’s simply a pose struck in front of the Eiffel Tower, it only serves to document that you’ve been there. A more candid shot, however, may speak not only of the locale, but the activities, the appeal, the fun you’re having, the kind of people you’re meeting, what you’re eating, perhaps even opening or closing a story. Your frames might show both a nice introspective closeup of a chimpanzee (Pan troglodyte,) but also communicate the behavior of others in such circumstances, like the image at top. Very slight changes in shooting technique may turn lots of subjects into abstracts, which can be used in countless ways. You might illustrate the anatomy of a reptile, and its habits, its habitat, its food source, and throw in some artistic and expressive frames as well.

When traveling, most people like to get their traveling companions in the frame with something that speaks of their location, which is great – but if it’s simply a pose struck in front of the Eiffel Tower, it only serves to document that you’ve been there. A more candid shot, however, may speak not only of the locale, but the activities, the appeal, the fun you’re having, the kind of people you’re meeting, what you’re eating, perhaps even opening or closing a story. Your frames might show both a nice introspective closeup of a chimpanzee (Pan troglodyte,) but also communicate the behavior of others in such circumstances, like the image at top. Very slight changes in shooting technique may turn lots of subjects into abstracts, which can be used in countless ways. You might illustrate the anatomy of a reptile, and its habits, its habitat, its food source, and throw in some artistic and expressive frames as well.

Even if you have a distinctive purpose in mind, such as an assigned shoot, it helps to periodically remind yourself what exactly the purpose is, and if there are multiple ways of approaching it. This might mean that, in an article about Alaskan wildlife, you not only get a photo of a caribou, but include something that speaks of the environment, conditions, or flora in the frame as well. And the more ways you approach something, the greater the opportunity for it to be used elsewhere. You might wait for a subject to look up or resume eating, or a model to appear relaxed or thoughtful. No one needs to smile for photos, and in many cases they’re much more expressive when you capture them in honest emotions, but the photographer should try for a range.

Remember, too, that when shooting people, they almost always see themselves differently, so getting a wider range of expressions and angles greatly improves the chances that you’ll get a shot that they like. A photo that you might be particularly proud of may be very damaging to your ego when your model rejects it out of hand, since you never considered how sensitive they were about their earlobes or whatever. Your purpose in such cases is not to promote yourself, but to please them, so you should be finding out more of what they like while getting a good variety of approaches anyway.

I will also stress something that I have to remind my students of: shoot both horizontal and vertical formats. While many subjects dictate what works best by their very nature, such as full-length portraiture nearly always working best in vertical, some subjects can appear well in both, and provide a different flair in either. I almost never shoot with the intention of using an image as a banner or panoramic, but the header images at top, which I keep adding to, prove that many frames can be altered to fit anyway. And again, this opens up further options for publication, since editors may have particular constraints depending on the layout they have to work within.

The other benefit that thinking of purpose provides is weaning the photographer away from grab shots and straightforward compositions. There’s a thing called “inattention blindness” that has recently gained a lot of attention (a ha ha) on the web, mostly in videos featuring gorilla costumes, but what it means is we can focus all of our attention on one particular aspect of a scene and fail to even register anything else plainly within our field of vision. It happens very frequently in photography as we try to catch the action, establish the pose, or make sure our subject is sharply focused, so considerations of purpose leads to breaking this narrowed attention and examining the frame more, seeing the possibilities inherent from the background, or a change of position effects the composition, or different lighting, and so on.

The other benefit that thinking of purpose provides is weaning the photographer away from grab shots and straightforward compositions. There’s a thing called “inattention blindness” that has recently gained a lot of attention (a ha ha) on the web, mostly in videos featuring gorilla costumes, but what it means is we can focus all of our attention on one particular aspect of a scene and fail to even register anything else plainly within our field of vision. It happens very frequently in photography as we try to catch the action, establish the pose, or make sure our subject is sharply focused, so considerations of purpose leads to breaking this narrowed attention and examining the frame more, seeing the possibilities inherent from the background, or a change of position effects the composition, or different lighting, and so on.

I always strongly discourage the use of the LCD on the back of digital cameras for use as a viewfinder if the camera actually possesses an optical one, for numerous reasons such as stability, the inaccuracy of exposure, and the inability to tell whether the image is truly sharp. But among them sits the frequent display of camera info in the very frame you should be using only for your subject. Battery life, image number, jpeg compression, f-stop, and all that jazz serves only to crowd your composition into the middle, out from under all this unnecessary detail, so either use the viewfinder, or shut off the info display. You will use the whole frame, and get much more dynamic when composing.

And finally, to learn from my own difficulties, it helps to get a variety of angles not only of any critter you might want to identify later, but also of any plant that they’re perched on or eating from. Identifying characteristics vary greatly by species, so the more sides and detail you have, the better your chances of confirming the ID. When in a botanical garden or zoo, you can even take images of the identifying plaques or displays, having them handy right in sequence with the species in question, and even linked by date by the EXIF info within the image file itself. And of course, the exterior shot of the facility also serves as a reminder. When shooting weddings, I used to set up an artistic shot of the wedding program, which could be used not only as an album opener, but was my own reference for just who the happy couple was ;-).

So, apply a little thought, and keep those purposes in mind – it may come in handy down the road.

During the previous transit in 2004, I was living in Florida and had a basic Galilean telescope that might have produced some nice tight shots from the sunrise event, had a single towering thunderhead not obscured the sun until well after the transit ended. It was, quite possibly, the same thunderhead that I’d been doing time-exposures of hours before, which I think means, “You win some, you lose some.”

During the previous transit in 2004, I was living in Florida and had a basic Galilean telescope that might have produced some nice tight shots from the sunrise event, had a single towering thunderhead not obscured the sun until well after the transit ended. It was, quite possibly, the same thunderhead that I’d been doing time-exposures of hours before, which I think means, “You win some, you lose some.”

Anyway, yesterday I discovered that the creature scarfing the tops of some of our tomato plants was not the suspected deer in the neighborhood, but a fat tobacco hornworm, the larval stage of a six-spotted sphinx moth (Manduca sexta,) closely related to, and often mistaken for, the tomato hornworm, larva of the five-spotted hawkmoth (Manduca quinquemaculata.) The bane of tomato-growers everywhere, hornworms aren’t really difficult to get rid of, for the home grower anyway – while a little hard to spot, all you have to do is pluck them off and fry them up with a little vinegar and hush puppies. All right, seriously, don’t follow that advice, because hush puppies aren’t very good for you. But I suspect people have more of a fear of hornworms since they’re huge as far as caterpillars go, bloated like a Hut, and have a nasty-looking little rapier on their hinders. Since I haven’t ever been tagged by either end of a hornworm, even years ago while fretting over not getting a Star Destroyer for christmas, I’m inclined to say the fears are unjustified. My subject here reluctantly served as a photo model before taking a dip in a nice cool and refreshing bucket of water (they’re also terrible swimmers.) Hey, don’t judge me, this is natural selection; just like tearing into a beehive for honey is a bad move, messin’ with a human’s tended garden is Darwinism at its most efficient.

Anyway, yesterday I discovered that the creature scarfing the tops of some of our tomato plants was not the suspected deer in the neighborhood, but a fat tobacco hornworm, the larval stage of a six-spotted sphinx moth (Manduca sexta,) closely related to, and often mistaken for, the tomato hornworm, larva of the five-spotted hawkmoth (Manduca quinquemaculata.) The bane of tomato-growers everywhere, hornworms aren’t really difficult to get rid of, for the home grower anyway – while a little hard to spot, all you have to do is pluck them off and fry them up with a little vinegar and hush puppies. All right, seriously, don’t follow that advice, because hush puppies aren’t very good for you. But I suspect people have more of a fear of hornworms since they’re huge as far as caterpillars go, bloated like a Hut, and have a nasty-looking little rapier on their hinders. Since I haven’t ever been tagged by either end of a hornworm, even years ago while fretting over not getting a Star Destroyer for christmas, I’m inclined to say the fears are unjustified. My subject here reluctantly served as a photo model before taking a dip in a nice cool and refreshing bucket of water (they’re also terrible swimmers.) Hey, don’t judge me, this is natural selection; just like tearing into a beehive for honey is a bad move, messin’ with a human’s tended garden is Darwinism at its most efficient.

I should probably feel a bit insulted, since my model here (I believe this is a Chinese mantis, Tenodera aridifolia sinensis,) undertook its meticulous foreleg cleaning efforts immediately after I’d coaxed it to walk on my hand for the scale shot. Or perhaps this is a measure of mantis respect. My friend here is better than twice the size it was when I first found them and got the dew pics, about 4 cm in length, but still well below adult size (that’s my finger, in case it’s not clear.) Nobody has been cooperative enough to let me photograph the molting, even though I’m pretty certain it’s happened at least twice, judging from the color changes. The chances of my capturing this activity in images is slight, however; immediately after molting their chitin is still soft, leaving them very vulnerable, so they tend to perform the molt while hidden and remain so until they feel safe – the thick bushes provide plenty of opportunity for this. Still, I keep watching.

I should probably feel a bit insulted, since my model here (I believe this is a Chinese mantis, Tenodera aridifolia sinensis,) undertook its meticulous foreleg cleaning efforts immediately after I’d coaxed it to walk on my hand for the scale shot. Or perhaps this is a measure of mantis respect. My friend here is better than twice the size it was when I first found them and got the dew pics, about 4 cm in length, but still well below adult size (that’s my finger, in case it’s not clear.) Nobody has been cooperative enough to let me photograph the molting, even though I’m pretty certain it’s happened at least twice, judging from the color changes. The chances of my capturing this activity in images is slight, however; immediately after molting their chitin is still soft, leaving them very vulnerable, so they tend to perform the molt while hidden and remain so until they feel safe – the thick bushes provide plenty of opportunity for this. Still, I keep watching.

Returning to the question of what someone might stand to gain from a hoax aimed specifically at the UFO (or paranormal, or religious) community, one has to be unfathomably ignorant to ignore the amount of money someone can sell a story or a photo for, much less speaker’s fees and book rights. And in some cases, it may be true that “the general public” might find someone less than reputable, but the UFO community isn’t too discriminating and is more than happy to shower praise and huzzahs on even the weakest and least substantiated stories – and

Returning to the question of what someone might stand to gain from a hoax aimed specifically at the UFO (or paranormal, or religious) community, one has to be unfathomably ignorant to ignore the amount of money someone can sell a story or a photo for, much less speaker’s fees and book rights. And in some cases, it may be true that “the general public” might find someone less than reputable, but the UFO community isn’t too discriminating and is more than happy to shower praise and huzzahs on even the weakest and least substantiated stories – and