First off, your assignment for today: read the post found at The Diamond In The Window – it shouldn’t take five minutes. I’ll wait here and chase the cat off the keyboard.

oiuc3uvcdugfybel,,l

Done? Good. That was a great example of how too many school systems within the US have completely lost sight of their goals, and most especially, a demonstration of the issues with “teaching to the test.” I have no problems with saying that what I learned in English classes in school has virtually nothing to do with how I write, nor what I present here. I always did well in English class, and have been an avid reader since before I started school. But in my years of school, there was one book, just one, assigned in class that I actually enjoyed: The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. On the flip side, I am completely lost as to why anyone would bother with F. Scott Fitzgerald or John Knowles, not terribly impressed with William Shakespeare or Ernest Hemingway, and think John Steinbeck was a ham-fisted amateur at tragedy.

At this point, English majors and those who think the word “literature” is a mark of esteem would all be preparing to rip my writing apart in retaliation (presuming they had not already fled in horror long ago,) or at the very least assuring themselves that I’m certainly not sophisticated enough to understand such magnificent works. Never realizing, perhaps, that there is nothing that will be considered good by everyone, and such labels are merely expressions of opinion. The Appreciation of Literature is not something that we should aspire to, anymore than we should all have the same opinions of politicians, food, or hobbies; writing is about communication. If I’m completely put off by unrealistic depictions of human interactions, or obvious attempts to instill certain emotional responses, then that author is not communicating effectively to me. This is no more a fault of mine than it is of theirs.

I cannot, in the slightest, diagram a sentence anymore, and I haven’t ever regretted this in my life. I occasionally misuse words (perhaps even words like “occasionally,”) and could certainly write a bit clearer at times. But if anyone gets the gist of what I’m saying, and can read through without wincing in pain or getting confused, then I’ve done everything that writing is intended to do. If, by some infinitesimal chance, I manage to produce something that someone enjoys reading, that strikes their fancy or resonates or illustrates or enlightens, then I’ve gone beyond communication. That would be great, because that’s what makes people want to keep reading.

The authors that I like – Terry Pratchett and Brian Daley, Isaac Asimov and Douglas Adams and Gerald Durrell – are nearly all dead the ones responsible for how I write… because what they wrote is interesting, compelling, and entertaining. Sentence structure and the flow of prose do not come from classes, workshops, diagrams, and anal retentiveness, but from frequent exposure. None of the writers above will be considered within the realms of high literature, but if their writing keeps the reader involved, what more should anyone demand? Most importantly, why should anyone try to develop a ‘taste’ for writing based on what someone else deems worthy? Isn’t that simply sucking up to a perceived superiority?

‘Teaching’ and ‘learning’ are two concepts that are, far too often, poorly understood. Learning isn’t a special activity, nor does it take concerted effort. Humans learn as a matter of course, and we’re eager for new, interesting experiences. What we perceive through our senses is automatically stored in our brains – if we have reason to attach significance to it. Teaching is presenting information in a way that helps instill the significance, yet even saying that gives the wrong impression, I suspect. Significance isn’t fostered by putting more emphasis on certain words, or repeating things, but by tying the information into something that stirs an emotional response from the student, whether it be the sudden realization of how this applies to some aspect of their lives, or the discovery that a writer was sneaking in a hint of things to come, or simply that it came through a humorous method. You can’t diagram or structure a good teacher – nor can you judge a teacher by any particular student. Someone that reaches one student extraordinarily well may not reach another, because students are not blank slates cut from the same mold, but individuals with their own personalities.

In this way, I’m not going to agree with some of the comments on that linked post, the ones in essence saying, “Let the teachers teach.” Some teachers simply aren’t very good, and there really does need to be a way of determining such. But we’ve gotten immersed in a pile of standards within this country that now have little relation to anything useful for students. ‘Proper English’ is a completely misleading phrase, because there is no such thing. Language is simply effective communication, and it changes constantly. Nor is there any reason to maintain strict rules about it. The main reason I dislike Shakespeare is that the language has changed so much that his carefully-crafted passages, relying on the structure of the times, needs translation into current terms, changing the activity from following a storyline into building an edifice of context. An offhand double-entendre requires five minutes of explanation; everyone knows that explaining a joke takes every last vestige of humor from it.

Never, ever make reading (or any aspect of learning) a chore – that’s what we call a negative influence. Don’t over-analyze books or language. The term “prepositional phrase” is a sign of having too much time on your hands. Let the kids find the emotional response, the identification, the surprise of lost time because the book is too damn interesting to put down. And this will be different for every kid, and should be. When the student, on their own, starts on the next book from the same author, that’s your criteria of success.

And a hint to anyone who is called upon to administer testing and school curricula: teaching, good teaching, is not just technical, but emotional as well. Not everyone who can do a particular task can supervise others for the same task, and not everyone who knows the material can teach. What’s needed is someone who can produce the enthusiasm and spark the interest in their students, and a lot of that comes from possessing the same traits themselves. Crush that by trying to quantify it in some statistical manner, and you effectively stop someone from actually being a teacher. Or simply think back on the teachers that you preferred, and what classes you remember most. You might also think back on the jobs you yourself have held where the pay was inadequate; were you a good performer then? Did the employers who were micro-managers and clock-watchers produce a better workforce? Were you enthusiastic about going to work each day? Because, for someone to spark the enthusiasm in a student, they need to be enthusiastic themselves. Shit pay and the Sword of Damocles overhead is exactly the opposite of what’s needed.

Granted, most of our political parties benefit from a populace dumber than a bag of lint, which might explain many current trends in our overall educational system, but that’s another post…

I know this is a poor showing for National Wildlife Week, but hey, I think every week is National Wildlife Week, so chill. I been busy.

I know this is a poor showing for National Wildlife Week, but hey, I think every week is National Wildlife Week, so chill. I been busy. Now, I grew up arachnophobic, I’m not really sure why, and have made efforts to get over it, because spiders are cool macro subjects, and ubiquitous – I saw three different species in the immediate vicinity while shooting this one. I can handle most of the smaller ones, and actually like the various jumping spiders, even though my first memorable experience with spiders was with a jumper that I was convinced was a black widow instead [I removed a plastic protective cap from my backyard slide set one day when I was five or so, and a good-sized jumping spider leapt out and posed dramatically, hazzah! Since I had no idea what black widows really looked like, I figured the bigger and hairier, the more dangerous, not to mention only mean spiders would jump out like that; I screamed and slid down the slide simultaneously, and didn’t go back for days.]

Now, I grew up arachnophobic, I’m not really sure why, and have made efforts to get over it, because spiders are cool macro subjects, and ubiquitous – I saw three different species in the immediate vicinity while shooting this one. I can handle most of the smaller ones, and actually like the various jumping spiders, even though my first memorable experience with spiders was with a jumper that I was convinced was a black widow instead [I removed a plastic protective cap from my backyard slide set one day when I was five or so, and a good-sized jumping spider leapt out and posed dramatically, hazzah! Since I had no idea what black widows really looked like, I figured the bigger and hairier, the more dangerous, not to mention only mean spiders would jump out like that; I screamed and slid down the slide simultaneously, and didn’t go back for days.] “A” is the camera and lens setup, in this case a bellows and 50mm enlarger lens. It is highly recommended that this all be mounted on a slider of some kind to allow the camera to move closer to and further from your subject stage, which is how gross focus is achieved at such high magnifications. Here, I took pains to get the camera and stage at a height to make it easier to use from a chair, avoiding other pains such as a badly stiff back and neck from crouching. Learn from my trials.

“A” is the camera and lens setup, in this case a bellows and 50mm enlarger lens. It is highly recommended that this all be mounted on a slider of some kind to allow the camera to move closer to and further from your subject stage, which is how gross focus is achieved at such high magnifications. Here, I took pains to get the camera and stage at a height to make it easier to use from a chair, avoiding other pains such as a badly stiff back and neck from crouching. Learn from my trials. Fairly well I think, considering that nothing I used was designed to accomplish this. This is a

Fairly well I think, considering that nothing I used was designed to accomplish this. This is a

You can also do dark field work directly through the side of an aquarium, camera mounted horizontally like normal rather than vertically as shown above, but this reduces your flexibility a bit. First off, you’ll be waiting for your subject to hold still against the glass, or choosing a fixed subject (no, you’re not going to nail a free-floating subject with magnification this high, and you’ll die of apoplexy trying.) You typically have to move the camera every time the subject shifts, and with focus this short it often takes a couple of minutes to get everything back sharp – or even find it! And the sides of the tank introduce more distortion than simply shooting through the top surface of a film of water – a lot more, if they’re plastic and in rough shape.

You can also do dark field work directly through the side of an aquarium, camera mounted horizontally like normal rather than vertically as shown above, but this reduces your flexibility a bit. First off, you’ll be waiting for your subject to hold still against the glass, or choosing a fixed subject (no, you’re not going to nail a free-floating subject with magnification this high, and you’ll die of apoplexy trying.) You typically have to move the camera every time the subject shifts, and with focus this short it often takes a couple of minutes to get everything back sharp – or even find it! And the sides of the tank introduce more distortion than simply shooting through the top surface of a film of water – a lot more, if they’re plastic and in rough shape.

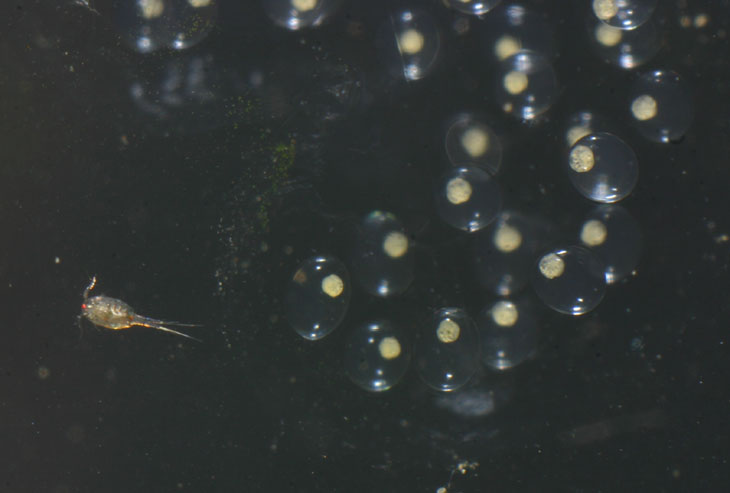

The main thing that I caught were snails and copepods, no surprise. Copepods are not-quite-microscopic aquatic organisms that are exceptionally common and definitely exotic-looking, but also hyperactive and hard to photograph, not the least because of their size. One can be seen in the photo at top, on the left. But the snails busied themselves with laying eggs all over the sides of the aquarium, also seen in that image, which means I’ll be holding off on switching this over to a saltwater tank for a little while, since this presents an opportunity that I don’t want to pass up: hatching! Seen here, one of the larger snails has been captured in the process of producing yet another egg sac, sticking it directly to the aquarium side. In natural conditions, such snails attach their eggs to rocks, twigs, and debris, usually in sheltered conditions – I had collected some others on dead leaves from the pond edges. If it helps, the snail itself is about 2 cm long – and the back end of the snail is towards the top of the image. Yeah, snail anatomy is kind of weird.

The main thing that I caught were snails and copepods, no surprise. Copepods are not-quite-microscopic aquatic organisms that are exceptionally common and definitely exotic-looking, but also hyperactive and hard to photograph, not the least because of their size. One can be seen in the photo at top, on the left. But the snails busied themselves with laying eggs all over the sides of the aquarium, also seen in that image, which means I’ll be holding off on switching this over to a saltwater tank for a little while, since this presents an opportunity that I don’t want to pass up: hatching! Seen here, one of the larger snails has been captured in the process of producing yet another egg sac, sticking it directly to the aquarium side. In natural conditions, such snails attach their eggs to rocks, twigs, and debris, usually in sheltered conditions – I had collected some others on dead leaves from the pond edges. If it helps, the snail itself is about 2 cm long – and the back end of the snail is towards the top of the image. Yeah, snail anatomy is kind of weird.  While I’m not going to be moving the egg sacs adhering to the sides, I can still transfer other subjects into the macro tank for better images. Aside from having clean and unmarked glass to shoot through, providing less distortion and things to scatter the lighting from, the smaller tank means that I can keep photo subjects closer to the front (less suspended sediment to shoot through,) manage the setting easier, and put my lighting anywhere it’s needed, including behind or underneath the tank. Tiny yet perpetually active subjects like this water beetle still have a lot of room to hurtle around within, but will now pass within view of the camera more often, and remaining focused at the water’s edge improves those odds quite a bit. Using the bellows like I was here requires manually closing the aperture down after achieving tight focus, which darkens the viewfinder pretty much to the point of ineffectiveness, so it means align the camera, focus sharply, and then close the aperture down and snap the image quickly before the subject gets bored and leaves, all while not bumping the rig in the slightest. The aperture needs to be quite small to extend the limited depth of field as much as possible; even with this, effective sharp focus is usually measured in millimeters. But with a small tank you can pick a particular area that is distinctive, focus and set aperture, then simply watch the tank without having to have your eye at the viewfinder, tripping the shutter when the subject enters your viewing area. This is helped by using a fairly high shutter speed and a flash/strobe to prevent any motion blur. A word of warning for those who want to try macro tank photography, though: at high magnifications, you find out just how hard it is to keep everything clean, and tank sides that appeared perfectly clear will show the hairs and schmutz that sneak in constantly. Often it’s hard to stay on top of the air bubbles that form constantly against the glass, requiring their dislodging just when you think you’ve got everything arranged, and as seen here, a tissue is a lot less useful to clean the outsides than you’d expect – those white squiggles are paper fibers. It goes without saying that difficult subjects always choose to pose helpfully right alongside something that you don’t want in the photo.

While I’m not going to be moving the egg sacs adhering to the sides, I can still transfer other subjects into the macro tank for better images. Aside from having clean and unmarked glass to shoot through, providing less distortion and things to scatter the lighting from, the smaller tank means that I can keep photo subjects closer to the front (less suspended sediment to shoot through,) manage the setting easier, and put my lighting anywhere it’s needed, including behind or underneath the tank. Tiny yet perpetually active subjects like this water beetle still have a lot of room to hurtle around within, but will now pass within view of the camera more often, and remaining focused at the water’s edge improves those odds quite a bit. Using the bellows like I was here requires manually closing the aperture down after achieving tight focus, which darkens the viewfinder pretty much to the point of ineffectiveness, so it means align the camera, focus sharply, and then close the aperture down and snap the image quickly before the subject gets bored and leaves, all while not bumping the rig in the slightest. The aperture needs to be quite small to extend the limited depth of field as much as possible; even with this, effective sharp focus is usually measured in millimeters. But with a small tank you can pick a particular area that is distinctive, focus and set aperture, then simply watch the tank without having to have your eye at the viewfinder, tripping the shutter when the subject enters your viewing area. This is helped by using a fairly high shutter speed and a flash/strobe to prevent any motion blur. A word of warning for those who want to try macro tank photography, though: at high magnifications, you find out just how hard it is to keep everything clean, and tank sides that appeared perfectly clear will show the hairs and schmutz that sneak in constantly. Often it’s hard to stay on top of the air bubbles that form constantly against the glass, requiring their dislodging just when you think you’ve got everything arranged, and as seen here, a tissue is a lot less useful to clean the outsides than you’d expect – those white squiggles are paper fibers. It goes without saying that difficult subjects always choose to pose helpfully right alongside something that you don’t want in the photo.

However, I soon became wracked with guilt over such blatant manipulations. Not to mention that, while searching through my images last night to illustrate a couple of presentations, I came across this insect photographed not six meters from my door one summer. While the wings are not being held in the right position, compare their pattern with that

However, I soon became wracked with guilt over such blatant manipulations. Not to mention that, while searching through my images last night to illustrate a couple of presentations, I came across this insect photographed not six meters from my door one summer. While the wings are not being held in the right position, compare their pattern with that