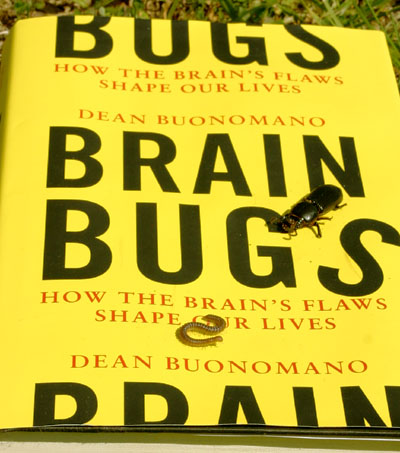

A friend of mine (yes, I have some, hush) handed this book over to me, because we’d had numerous discussions related to the content while he was reading it – and I was the one who initiated them without even knowing about the book. Anyone familiar with the content of this blog may be forgiven if they suspect it’s about insectivora, but that’s not the kind of bugs we’re talking about.

Brain Bugs: How The Brain’s Flaws Shape Our Lives, by Dean Buonomano, tackles a subject that we really need to be more aware of. The overall message is, humans possess brains that adapted to the demands of our development as a species over millions of years, and like nearly all other species on the planet, there are mechanisms that help us to survive. Problems arise, however, because these mechanisms are not precise, and most especially cannot differentiate between appropriate and inappropriate times to take effect. There are also basic brain functions that have strengths and weaknesses, depending on what we’re asking them to do.

Brain Bugs: How The Brain’s Flaws Shape Our Lives, by Dean Buonomano, tackles a subject that we really need to be more aware of. The overall message is, humans possess brains that adapted to the demands of our development as a species over millions of years, and like nearly all other species on the planet, there are mechanisms that help us to survive. Problems arise, however, because these mechanisms are not precise, and most especially cannot differentiate between appropriate and inappropriate times to take effect. There are also basic brain functions that have strengths and weaknesses, depending on what we’re asking them to do.

For instance, Buonomano points out that humans overall, when introduced to someone by name and vocation, will usually remember ‘baker’ as a vocation more accurately than ‘Baker’ as a name, simply because the vocation of baker has more connections to other things in our minds, such as fresh bread, flour, cookies, and so on – many of which may generate a positive response to us: “Mmmm, fresh bread!” While the name Baker is in a different class within our minds, even when being exactly the same word. That’s just the point – it’s not exactly the same word. Our brains are not a collection of discrete neurons, each representing a particular memory, but a network of connections among these neurons with varying strengths, which denotes their importance to us (and now I don’t feel quite as bad about being pathetic at remembering names.) The author touches on the chemical functions that make this work, and the structures that make up the brain itself, but only enough to explain how memory and thought processes take place, spending more time with what results these produce, and how this can affect our decisions.

Notable within is the large number of studies that Buonomano references, especially since this is a recently-published book and many of the works he cites are contemporary – if you have any interest in current science, you will almost certainly recognize at least some of the names or studies. As an amusing side note, I had read about the reactions to a priming study only a couple of days before reading about the same study in Buonomano’s book. The interesting aspect of all of this is that, regardless of the controls used in research, we’re still human after all, and not only might make mistakes during experiments (that still hasn’t been firmly established, lest I give anyone the wrong impression,) we can also respond to even the implication of such with something less than detached interest. It underscores one of the points made within the book: we aren’t terribly objective, but filter everything through our own personal outlook.

And, in too many cases, with some help from others. Since we’re a socially aware species, we take our cues from others very frequently, usually without realizing that it’s happening, and this can even lead to false convictions for felonies. While we like to believe that the ‘rational’ portions of our brains are in control, and our decisions are all considered and objective, in reality these functions are inextricably linked to the automatic responses we developed over thousands of generations. Studies have shown that patients respond more positively to being told that a procedure has a 95% survival rate, as opposed to being told it has a 5% mortality rate, even though these are technically the same exact thing. What we respond to are the words themselves to a large degree, coloring our impression of which is worse. Marketers and politicians, among others, are well aware of this, and exploit it to influence buyers/voters in a preferred direction; if nothing else, the cost of the book is repaid numerous times over by making the reader more aware of things like this.

Moreover, while finding out about brain functions that are less than optimal, the context of these within the evolutionary processes that spawned them makes marvelous sense, and Buonomano supports this with several cases of similar functions in other species. The ‘bugs’ aren’t necessarily flaws, but purposed towards other applications, and our egocentric perspective as higher beings has caused us to believe that we’re free from such effects. It’s a necessary shot of humility, in a way, while also being fascinating, and explaining a hell of a lot. As he points out, our development as a species took place over millions of years in largely the same type of environment, and only recently did we suddenly find ourselves in cities with abundant food and wide-scale communication; our brains are suffering from a degree of culture shock, and still trying to build campfires within our hotel rooms.

As an overview of cognitive function and how open to influence it is, this books does a great job, touching on numerous topics without getting too bogged down in details, yet Buonomano has delivered the essence while providing the sources of the details in an extensive appendix and bibliography. Since he covers a lot of territory, at times some of the points are presented quickly before moving on, and if you’re used to a single point per paragraph, you’ll need to pay closer attention. I also don’t want to give the impression that the book instills in the reader some kind of despair over trusting our thoughts; what it does is make the reader more aware of how we can be fooled, which can be sufficient to prevent it from happening – it’s at least a good start. While anyone already interested in critical thought would benefit from this book, it’s also a great way to begin the process itself. Though I admit that much of the material was not new to me, he still produces a lot of perspectives that are both insightful and useful tools in debate. On choosing political candidates:

What if upon voting for the president people were reminded of what is potentially at stake? A voter might be asked to consider which candidate they would rather have decide whether their eighteen-year-old child will be sent off to war, or who they would rather entrust to ensure the nation’s economy will be robust and solvent when they are living off Social Security. When the power of our elected officials is spelled out in personal terms presumably at least some voters would reconsider their allegiance to candidates who clearly lack the experience, skill, and intellect proportional to the task at hand.

I especially like the inclusion of the term “allegiance,” which implies (correctly, all too often) that voting is a function of loyalty rather than decision-making. It is in exactly this way that we can be influenced by how something is presented to us, and like Richard Wiseman, Buonomano slips in his own direct demonstrations, though not quite as many. While I wouldn’t recommend the book for readers below high-school level, it would serve as a great guideline for classroom activities for any age, and I can only encourage the inclusion of the overall premise in schools as a key part of the curriculum (admittedly, I say the same for critical thinking.)

Something that wasn’t very evident, that would have fit right in with the topic of the book, was how studies are usually structured to eliminate false positives and incorrect conclusions – basically, a rundown of how science is predicated around the idea that humans performing it are still fallible. Certain studies cited by Buonomano sounded far too imprecise to feel confident in the conclusions reached – see that link in the fourth paragraph – and while most were probably quite rigorous and structured, it was still an opportunity to examine how we try to correct for our cognitive foibles. That’s a minor (and personal) quibble in what is otherwise a surprisingly well-rounded tome, which fits nicely between the typical sound-bite ‘journalism’ and ponderous academic treatises. The style is not quite as casual as Big Bang, but neither is it hard to read. Definitely worth the time.

* * * *

In chapter 8, Buonomano departs from relating neurological functions that we’re confident in our understanding of, and (admittedly) speculates on the concept of religion throughout our species – I’m saving this topic for a later post, because it brings up countless facets all its own.