I’m the middle of a book that will be reviewed here upon completion (well, not right here, but up above somewhere,) and in the meantime, I keep running across thought-provoking content that I want to expand upon. I haven’t been taking notes, preferring instead to keep moving forward on the book, because it’s been taking a while – I’m actually doing much more writing than reading at this point (measured by time spent, anyway.) So I’m going to have to go back through and find all of the idea germs I came across earlier. Except for this one.

I had tackled this idea briefly before, and always had it in the back of my head as further speculation, and now some of the details within the book (no I’m not telling you what it is) have fleshed it out a little more. Brief synopsis: our minds have been shaped by evolution to be a certain way, far more than we typically expect. So the idea of finding “intelligent” life from other planets is, to put it mildly, problematic. This isn’t to say that it can’t happen, but that what we imagine it to be is probably way wrong.

I’ve said it many times, but we’re social animals. We’re geared to relate to one another, judging ourselves and our actions almost entirely by how others might see it, because we worked better as a species by developing these traits. We take this perspective for granted, believing that this is how it would always develop, and sometimes even believing that many other species have a similar perspective, in part at least. It takes a lot to demonstrate how narrow and vain this really is.

Take snakes as an example of animals that are unsocial (using this in a biological manner, not as a value judgment like we might use the word in conversation.) Their young are born fully mobile and immediately capable of feeding themselves, possessing the instincts and anatomy to do so, thus needing no care from an adult. Snakes obtain meals in a solitary manner, unable to achieve a benefit from “pack hunting” or whatever because their prey is singular and does not protect itself in a herd. On occasion, there are dens where many snakes might congregate, simply because it’s an ideal shelter in an area where such is sparse; they don’t do it for camaraderie, and in some such cases, when food is scarce too, they eat each other, or even their own young. While any of this might seem odd or distasteful to us, that’s the perspective talking, because it works remarkably well for the niche that snakes fill in the ecosystem. They have no social instinct because they’ve never needed it.

Most (perhaps all) bird species congregate in flocks, primarily because they gain a huge protective advantage from the multiple opportunities to spot danger and alert all others, additionally because their food sources tend to come in large amounts of seeds, berries, or even schools of fish, so there is more benefit from feeding among the others than competition from doing so. They also have to care for their young in the early stages, so often form parental bonds to share the workload. Birdsong is largely related to territory, part of the competition that they do face amongst themselves, which is reproduction. And this reproduction produces an extensive behavior all its own, that of selecting a mate that appears better than the rest, which fostered various displays of fitness in the form of plumage, shelter construction, and the song repertoire of an experienced survivor. People familiar with pet birds can usually see this difference in sociability, often misinterpreted; birds like their heads and backs scratched mostly because their new feathers itch and cannot be reached there, and prefer to perch on shoulders because it’s a dominant position.

Most (perhaps all) bird species congregate in flocks, primarily because they gain a huge protective advantage from the multiple opportunities to spot danger and alert all others, additionally because their food sources tend to come in large amounts of seeds, berries, or even schools of fish, so there is more benefit from feeding among the others than competition from doing so. They also have to care for their young in the early stages, so often form parental bonds to share the workload. Birdsong is largely related to territory, part of the competition that they do face amongst themselves, which is reproduction. And this reproduction produces an extensive behavior all its own, that of selecting a mate that appears better than the rest, which fostered various displays of fitness in the form of plumage, shelter construction, and the song repertoire of an experienced survivor. People familiar with pet birds can usually see this difference in sociability, often misinterpreted; birds like their heads and backs scratched mostly because their new feathers itch and cannot be reached there, and prefer to perch on shoulders because it’s a dominant position.

Now take humans. Most of our concepts of fairness and morals come from ideas of equitable distribution of gains, which throughout most of our evolutionary history was food, but the distribution thing is only necessary if food is a communal effort, such as hunting large animals and farming. We have young that are worthless for months, so require extensive dedicated care, and have the instincts to provide this, as well as maintain a parental pairing at least. We like the bright colors of ripe fruits and vegetables, and of the flowers that indicate where such will appear later on. We possess not just the ability to vocalize distinct sounds, but the ability to easily distinguish them as well, supported by bones that had once been the jaw levers of our distant ancestors, and this system probably assisted in coordinated hunting, later a foundation of language and the rapid dissemination of accumulated knowledge.

At some point in the past, we split off from our primate cousins and took to the grasslands instead of the trees, developing the bipedalism that enabled us to pursue large collections of protein on the hoof, which might have been a significant part of our developed brains. At the same time, our forelimbs no longer had to remain free to grasp limbs or serve as locomotion; we could now carry things for long periods, and the concept of possession could develop. Like many species, we at some point developed rudimentary counting skills – two bananas (ooh!) are clearly better than one, especially when the ripe season is brief and we may not find food again tomorrow.

Those manipulative forelimbs are pretty important. They contain multiple independent digits, legacy of millions of years previously when the progenitor of all land critters evolved away from fins into something that pushed and gripped the earth rather than slapped against the water; the number remained five for nearly everything, though they might have changed position or importance in many species – even horses have the vestigial remains of the remaining four while relying on one that specialized into a hoof. When we freed our hands from locomotion, they could be used to manipulate tools.

The idea of manipulation remains ingrained, displaying extremely early in our young and reflected in our ability to count, and interwoven throughout our language even in abstract concepts that cannot ‘move’ in any way. It was incorporated into two other, very key concepts: cause-and-effect, and an overriding curiosity. Somewhere along the way, we refined the ability to piece together the basic ideas into a ‘puzzle’ concept, not just for noticing the behavior of our prey and predators, but into figuring out that the grain planted in the spring became the food source of summer, and stored correctly, the food source all winter too. It’s an intricately developed system, too, in that we get an immediate internal response, delight, in solving puzzles, on top of the subsequent advantages of food somewhere along the way. Few other species have this, and certainly not to the extent of developing scientific laws and figuring out light.

And yet, throughout all this, we are dominated by status, competing amongst ourselves for improvement and recognition, born from sexual selection and the prestige (and likely greater share of resources) of the leader of the clan. It’s important to have the newest videogame system, even when this probably isn’t contributing to sexual selection very effectively. In fact, the rational part of our minds has to ponder carefully to find any value at all – it satisfies that puzzle drive and in some cases the competitive one. It’s not the reason why we compete that serves as the motivation, just that we do; it’s still a half-assed system that can be fooled easily, as is the sexual drive which can be satisfied without procreation at all.

Another factor that comes into play is our time to mess about with book clubs and artwork. In many species, the balance between finding food, avoiding predators, and maintaining shelter takes up all available time; there is nothing resembling “leisure.” For us to have the time we do, we had to inhabit (or create) a niche where these demands were minimized: few predators, dependable food sources, lasting shelter, and so on. Some of this likely came about from our own efforts, sparked by those clever bits in the brain; others may have been a product of the climate, or other species interacting, a right-place-right-time scenario where there were abundant prey animals right on top of good shelter materials.

All of these things make us what we are, and there are other bits in there that we really don’t know at all: why our brains developed so distinctly in this direction, whether the protein source (as in the available prey) or the protein demand (larger brains) came first, how much of it was driven by changing climate or coincidental events, and so on. Having built all that, perhaps now it seems strange that we somehow believe alien species will be a lot like us.

But let’s assume that some extra-terrestrial species developed in a similar enough way that they have a language, whether expressed in sounds or light flashes or scents. We have to consider that we’re highly unlikely to ever be able to understand it. Our language relies on numerous species-wide ideas and conclusions – that manipulation thing mentioned earlier, for one: [noun] [action verb] [noun] [adjective], with nouns representing discrete concepts such as you, or Australia, and with verbs representing broad varieties of individual action based on movement, possession, and even abstract ideas. Take the simple sentence, “Al slowly writes the blog post.” “Al,” in this case, pertaining to myself, but only because we form a narrow frame of reference and seek the most likely candidate for this pronoun from among the millions of people this could apply to, accepting automatically that this must be a name and not a title, object, place, or cultural convention such as, “January.” Then we get to “slowly,” which modifies the verb we haven’t even gotten to yet and only makes sense from the standpoint of comparison against other examples not mentioned. “Writes” is both a physical action and a mental one, describing a complicated process of forming thoughts into sounds that represent common ideas among ourselves, then converting those into symbols, and recording them to be retained for a period of time, communicating with others that I have never met and have no worthwhile reason to engage with – it’s certainly not putting food on the table or protecting my nonexistent offspring. And then, what’s a “blog post?” The mere physical description of this takes in the peculiar medium of electronic info and representations of symbols through contrast on a monitor, while the overall purpose is so broad as to defy a useful description. Now try interpreting this correctly as a species which doesn’t use pronouns, or doesn’t use group ideas such as “people” but represents each individual separately, or cannot see color or contrast but only three-dimensionality (thus unable to even fathom “information” on a flat surface,) or doesn’t have the same emotions so has no concept of vanity or attempting to share ideas. Many of our words we don’t define at all, but just use in context: tell me what “is” means without using it. When you get that far, explain why we would even need it; of course something “is” a certain way – how else would it be?

Think that’s fun? Now imagine you’re faced with a new alien species, and want to ask it a question. The species is not only not going to understand your language, it almost certainly won’t interpret the voice inflections we use to differentiate a question from a statement, has no idea what your raised eyebrows mean, won’t understand why your finger keeps going back and forth in odd directions, might consider being touched a grave insult or the symbolic transmission of microbes, and might treat lasting eye contact as blindness – you already saw it, why do you need to keep looking? We can’t even imagine what we’d have to do to communicate because we cannot get out of our own frame of reference, or even fully comprehend what our frame of reference really is.

We have examples of ancient writing that we have never interpreted, despite the fact that not only did it come from humans, we have pretty solid ideas of what we would want to write about in the first place. We spend years trying to figure out what goes on in the minds of species that we have easy, constant access to, like dogs or porpoises, and most of what we provisionally ‘know’ we’re not very confident with. We have multiple ways of even representing our ideas in a visual manner: English is based on “symbol=sound,” while many Asian languages work with “symbol=discrete idea,” close but not comparable to pictographic languages which portray events more like a cartoonist than a novelist, sometimes utilizing “symbol=trait.” The Rosetta Stone was such a remarkable find because it gave the same story in multiple languages side-by-side, serving as the key to translation that had been eluding archaeologists for decades. These are, again, difficulties within our own species, in the common frame of reference of same emotions, same manner of living, same planet.

What does all this mean? There’s no conclusion to be found, save for the very high likelihood that we wouldn’t even know something was trying to communicate, much less what it might be – with the additional idea that communication might be a very, very bad idea, which we have difficulty recognizing because, even as hostile as we’ve been to our own species in the past, we still function as a social group.

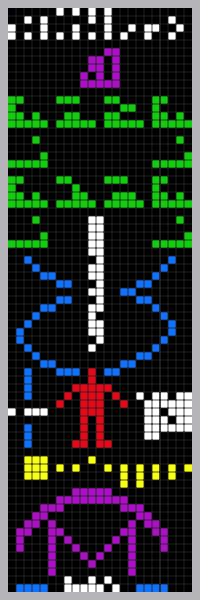

The image at right is a message we sent into space – kind of. First off, no one really believed it would be received, so it’s just a representation of what we might send, were we trying to communicate. Second, it was a binary signal, so the grid layout and the colors did not actually exist at all; you’ve got a small advantage in that you can see a two-dimensional version with differentiations among elements, something no extra-terrestrial species would have. And I say you have this advantage because it is your assignment to interpret this message. What does it say?

Even the simple first element, a binary representation of the numbers one through ten, is hard to fathom, but it’s necessary to understand the next several, which use the same structure to produce some key bits which should be universal: atomic weights. But then the message changes languages to do pictures, including the only one that most people would likely recognize, which is the human. Or videogame character, at least – the proportions are a little off for humans. And of course, no picture is formed at all if the grid layout is not interpreted correctly. We sit here, part of the species that created this message, sharing the same perspective and having a pretty good idea what we’re inclined to say, and likely couldn’t translate all of this effectively (the full description is here, by the way.) How many misinterpretations are possible from this? Perhaps that we emanate DNA from our heads? That the Earth is out of the plane of the ecliptic, or roughly 11% the size of the sun? That the telescope is nearly the size of our entire system? Man, those aliens don’t stand a chance…

* * * * *

I’m going to throw in another little bit, loosely related but not quite on the same subject. All of that stuff above would also apply to any supernatural being that might exist. The emotions, outlooks, and even rudimentary thinking skills that we possess all serve to help us survive, none of which would be necessary, functional, or even make sense for a god; what use would a singular, hyper-potent being have for sympathy, fairness, judgment, or even time passage, curiosity, or creation at all? Would such a being be amused by this, or have desires of any form, much less the displeasure or goal-seeking that are always credited to it? What would such desires be there to accomplish? We can easily imagine bacteria having no need for these, but they are biologically much, much closer to us in development and environment than all of our concepts of supernaturality. The idea that any such being would be as similar to us as world religions repeatedly avow becomes ludicrous, even as speculation – but it is something we evolved to expect.