I wish I could draw political-style cartoons, because then I’d open this with an illustration of an unkillable zombie, or maybe Jason from the Friday the 13th franchise, with the label “Free Will” on it…

This time around it’s an article in Slate from Roy F. Baumeister entitled, “Do You Really Have Free Will?” Baumeister is an ’eminent social psychologist,’ which may explain why he only approached the concept from the psychological angle. Unfortunately, that’s not really where the issue lies in the slightest, and in a way, this makes me glad I never got edumacated since now I can consider topics from angles other than my own narrow specialty.

It’s almost a rule that, when the title of an article asks a question, the answer the article will come to is, “no.” Baumeister, perhaps consciously, thwarts this by maintaining that yes, indeed you do have free will – but then again, it’s there in the subtitle: “Of course. Here’s how it evolved.” To support this, however, he chooses to define free will in his own way, and ignore all of the other points raised ad nauseum over the years. It’s a shame, because the article starts off promising enough:

It has become fashionable to say that people have no free will. Many scientists cannot imagine how the idea of free will could be reconciled with the laws of physics and chemistry. Brain researchers say that the brain is just a bunch of nerve cells that fire as a direct result of chemical and electrical events, with no room for free will. Others note that people are unaware of some causes of their behavior, such as unconscious cues or genetic predispositions, and extrapolate to suggest that all behavior may be caused that way, so that conscious choosing is an illusion.

Good – at least he’s aware of the many points raised, and the original article has links throughout this paragraph to send the reader in search of more info.

Yet, he addresses none of these, treating them as he hints at in the above paragraph as being from a narrow perspective, which he then perpetuates. He says,

Scientists take delight in (and advance their careers by) claiming to have disproved conventional wisdom,

but then,

These arguments leave untouched the meaning of free will that most people understand, which is consciously making choices about what to do in the absence of external coercion, and accepting responsibility for one’s actions.

Well, yes, that’s the conventional wisdom. The point is, physics operates in very predictable ways, and we are physical beings – the rather obvious conclusion is, we should be able (in theory) to predict what our decisions would be, and that means everything we do is determinable, and thus determined since the start of the universe. The “in theory” part is there because the amount of information necessary to do this is so vast we don’t have words to describe it, and it does recognize that there are probably laws of physics we don’t even know yet. Doesn’t matter – what we do know is working pretty damn well.

Naturally, this leads to the concept of determinism, or predestination if you prefer, and the simple extrapolation from there that we didn’t make the decisions, they were just a byproduct of the physics involved. Which then trashes Baumeister’s simple definition above. The coercion isn’t external, though, it’s internal. Is that what Baumeister is talking about, or isn’t it? Doesn’t matter – it’s what nearly everyone else is talking about, so if he is purposefully avoiding the subject in this manner, he isn’t actually addressing the topic.

Which is funny, because at times, he makes very pertinent points:

There is no need to insist that free will is some kind of magical violation of causality. Free will is just another kind of cause. The causal process by which a person decides whether to marry is simply different from the processes that cause balls to roll downhill, ice to melt in the hot sun, a magnet to attract nails, or a stock price to rise and fall.

Excellent! Yes, our brains are made up of physical matter, and what they do is based in physics. But then,

Different sciences discover different kinds of causes. Phillip Anderson, who won the Nobel Prize in physics, explained this beautifully several decades ago in a brief article titled “More is different.” Physics may be the most fundamental of the sciences, but as one moves up the ladder to chemistry, then biology, then physiology, then psychology, and on to economics and sociology—at each level, new kinds of causes enter the picture.

No. Wrong. In fact, horseshit. There are no different causes. What anyone is using in such cases are what are sometimes called emergent properties, or to be less pedantic, a collective process that just makes conversation easier. Stuff that we eat performs the same chemical energy exchanges as everything else in the universe, but because it occurs in a specific manner common to many species, we call it “digestion.” It is not a different cause – it is simply an easier and more specific term than, “exothermic reaction,” or even, “entropy.”

And therein lies much of the problem, because it is the very idea that there is another ’cause’ that sets off so much of the debate, from those trying desperately to support their idea of a soul or those who like the dualistic mind concept. Does Baumeister address these? No.

As Anderson explained, the things each science studies cannot be fully reduced to the lower levels, but they also cannot violate the lower levels. Our actions cannot break the laws of physics, but they can be influenced by things beyond gravity, friction, and electromagnetic charges. No number of facts about a carbon atom can explain life, let alone the meaning of your life. These causes operate at different levels of organization. Even if you could write a history of the Civil War purely in terms of muscle movements or nerve cell firings, that (very long and dull) book would completely miss the point of the war. Free will cannot violate the laws of physics or even neuroscience, but it invokes causes that go beyond them.

One of the many benefits of the scientific approach in the past century has been crossover – biology tying in firmly with chemistry, astronomy tying in irrefutably with atomic physics, and even psychology meshing in surprising ways with genetics (please don’t take that to imply, in any way, that psycho-social disorders are all genetic.) What we have found is that physics, deep down, combines them all. Baumeister implies above, perhaps only as misdirection, that physics applies only on the active level, muscles and nerves, and that the mind is something else. Like everyone that takes this stance, he never bothers to explain how this might be and where it occurs.

No number of facts about a carbon atom can explain life,

Well, yes, they can – mostly they tell us that our common definition of “life” doesn’t really apply very distinctly, and needs to be fudged for every application. An atomic chain reaction performs many of the same functions of life, in energy release and sustained reactions, as does fire. If we want it to mean replication of genetic material, viruses do that, but perform no energy exchanges on their own (they co-opt a host cell to for that function.) So, what definition of “life” is he referring to here?

…let alone the meaning of your life.

… annnd so casually, almost negligently, Baumeister introduces a philosophical angle without the faintest provocation. I’m game – what is the meaning of life, from free will, or the psychological angle, or indeed, any goddamn perspective you care to name? Baumeister doesn’t have it either – no one has given it a solid go, honestly – but apparently we are to believe it is a failing of all those vermin who deny free will when they cannot produce it. Tactics like this annoy the piss out of me, and it’s much worse from someone who isn’t grasping his topic very well.

As for physics explaining how the Civil War came about? You’d be surprised at how much it truly can tell us. DNA is a string of molecules bound by and replicated with mutual properties of attraction, the energy exchange of chemical bonds dictated by valences. These strings of molecules guide cells in protein development, which determines what kind of body traits develop, including ‘instinctual’ traits of the brain. Natural selection is a numbers game – whatever organism survives/reproduces best is able to spread its genetic heritage throughout a population faster than others. This gives rise to traits that tend to help the organism (and by extension species) survive. Among the traits that humans developed over their long history are fairness, cooperation, and functions that support tribal cohesion and produce negative reactions to being taken advantage of. At the same time, humans compete for limited resources, and preferred mating status, and optimal social standing. That pretty much describes economics in its entirety, not from a definition standpoint, but from an evolved behavior one – and economics (and fairness, and competition, and so on) pretty much explains the Civil War – in fact, most wars. The path might be very convoluted, and be broken up into distinctions such as ‘cell division’ or ‘proxy-based trade system,’ but it’s not as if physics isn’t involved on every level.

Baumeister is outright saying here that the path isn’t this clear, instead involving some special step therein that thwarts physics and gives rise to the special property of free will – even when admitting earlier that free will is part of the causality of physics. This seems to indicate that he hasn’t really thought the matter through all the way.

The evolution of free will began when living things began to make choices. The difference between plants and animals illustrates an important early step. Plants don’t change their location and don’t need brains to help them decide where to go. Animals do. Free will is an advanced form of the simple process of controlling oneself, called agency.

So, does the sunflower choose to follow the sun? Does the oak tree choose to split and lift the rock? If not, what are they using, and how does it differ from agency and free will? Biologists know that they do not, and that all such distinctions are merely arbitrary divisions in the spectra of living functions. We often create divisions for convenience, but this does not mean such divisions are truly distinctive and separable.

Decision-making is just the same. Faced with two or more choices, we have functions that compare the consequences to select what choice is most to our benefit, for whatever criteria seems to apply – and to assign importance to this choice, making us motivated to consider carefully rather than flippantly (most times, anyway.) This is the realm of emotions, the positive/negative feedback functions we have that we even see in other species to varying degrees (those that want to argue that dogs or mice, for instance, do not have emotions have to define what exactly emotions are first.) But are these different than the functions within a seed that make it sit dormant, in an envelope perhaps, until surrounded by water and nitrogen-rich soils? How does a seed ‘decide’ to sprout?

It doesn’t – ‘decide’ is misdirection. When the conditions are right it occurs. And much the same can be said for free will, which in most uses is the importance we feel in making a good decision. This importance is what makes us react when we’re told we don’t have it, but this is misunderstanding. The deterministic traits of physics also dictates the presence, and activity, of this importance within us. And Baumeister largely says this, but in tortured, ridiculously misleading ways.

Living things everywhere face two problems: survival and reproduction. All species have to solve those basic problems or else go extinct. Humankind has an unusual strategy for solving them: culture. We communicate, develop complex social systems, engage in trade, accumulate knowledge collectively, create giant social institutions (governments, hospitals, universities, corporations). These help us survive and reproduce, increasingly in comfortable and safe ways. These large systems have worked very well for us, if you measure success in the biological terms of survival and reproduction.

If culture is so successful, why don’t other species use it? They can’t — because they lack the psychological innate capabilities it requires. Our ancestors evolved the ability to act in the ways necessary for culture to succeed. Free will likely will be found right there — it’s what enables humans to control their actions in precisely the ways required to build and operate complex social systems.

Well, no – all that crap is simply anthropocentrism, the idea that humans are special. There are countless ‘cultures’ throughout the animal kingdom, if you bother to define it as common behavioral traits – canids have packs, birds have flocks, whales have pods, bees have hives, meerkats have communal child care, chimps practice adoption, and nothing destroys its environment like we do. Let’s not lose perspective.

All of that is evolved behavior. We can assign any portion thereof a fancy name if we like, but doing so doesn’t make it free from physical laws; we seem able to accept this easily when it comes to other species, just not for us. We’re different.

No, we’re not. Whether we like or dislike some fact of the universe doesn’t make it right or wrong, and the sooner we recognize this, the better. Right and wrong are also survival traits, in fact, part of that decision-making process. But they are also badly abused by misapplication. Decisions can be beneficial or detrimental; people are not right or wrong, and most especially, bare facts never are. They simply exist. However, the ill-feelings that people get when they believe that physics denies something that they consider to be important is responsible for all sorts of semantic jousting.

If you think of freedom as being able to do whatever you want, with no rules, you might be surprised to hear that free will is for following rules. Doing whatever you want is fully within the capability of any animal in the forest. Free will is for a far more advanced way of acting. It’s what a creature might need in order to adjust its behavior to novel situations, to get what it wants while still following the complicated rules of the society.

This is all just utter nonsense. The complicated rules of society are just the desires within us to act cooperatively rather than individually – just like hyenas and sardines. We’re getting so far off base now it’s frightening. From a cognitive psychology standpoint, this is a hopeless jumble of motivations. We have social tendencies because we worked better in groups than as individuals. We view decisions as important to accommodate the nature of choice – automatic reactions do not leave room for individual variation or changing conditions, so the ability to weigh consequences evolved. Many of our decisions are badly biased by group influences, as can be seen everywhere, while ‘free will’ is, as Baumeister describes it at least, a fiercely independent trait. But in reality they’re indistinguishable – our desire to ‘go with the flow’ will be treated internally just as important as our desire to think independently, because free will is the desire.

The vast majority of species that reproduce sexually select their mate from among many choices. Is this free will? You can call it that if you like, because we define such things arbitrarily just to make communication easier, but this in no way implies that it is a special property. Does the ability to select mates, or nest locations, or foods, make physics stop working as we know it? It’s a ludicrous question, isn’t it? Yet everyone who maintains that free will is a separate, special property is making exactly this argument. Regardless of how you might want to define it, there’s still an underlying set of laws, and these laws tell us, very distinctly and dependably, that energy behaves like this, all of the time, and matter will do this with the application of this much energy, all of the time. No linguistic two-step changes this in the slightest, regardless of how much anyone wants to draw imaginary lines around their favored domain.

But all of that is ignored in toto by Baumeister, which is a shame, because that’s where the debate lies. While he touches briefly on humans operating within physical laws without special properties, he somehow manages to avoid the consequences of this on the asinine concept of free will. And while touching lightly on evolutionary psychology, he nevertheless approaches the topic more from the dualistic brain/mind separation favored by too many philosophers and routinely dismissed by the majority of biologists.

And so, I’ll say it again. Determinism is highly probable – in fact, the only thing we have evidence of, like it or not (and if you don’t like it, at least try to find a good reason to deny it, rather than sophistry-laden philosophical arguments or the grave misunderstanding of quantum indeterminacy.) The functions within us, as determinable as they might be, also work to see that we are pleased with the act, or illusion if you prefer, of decision-making, and whether people eventually stop using the idiotic concept of free will or not will not ever change this. The universe might have a specific outcome, which we could see if we were omniscient, but we’re not, and we can treat life as a journey into the unknown as much as we do any coin toss (also, quite easily, determinable by physics,) any sports game, any movie we haven’t seen or person we haven’t met. While we dance among everything else in the rules dictated by atomic forces, what we experience and enjoy are the interactions we have and the bare fact that we don’t know what is to come. And that hasn’t changed.

This is largely a continuation of an earlier post, where I went in too close to a particular species of spider, and I’m going to do it again. It’s all legal if I provide a warning.

This is largely a continuation of an earlier post, where I went in too close to a particular species of spider, and I’m going to do it again. It’s all legal if I provide a warning.

The body length of my Tetragnatha specimen, eyes to abdomen tip, is around 11mm – the chelicerae alone are roughly 5mm folded. The legs at maximum stretch (meaning in the straight line hidey mode that lets them blend in with water reeds and twigs) may exceed 80mm – the forelegs alone are 52mm in length. Which means that enterprising tiny spiders like the one shown at right, only a millimeter in body length, can spin a web between the legs of a dead Tetragnatha as if it’s a tree, and come along for the ride when one is collected to serve as a photo subject. She’s still there, annoyed at how often I shifted her scaffolding to get better angles but otherwise unaffected. And yes, you’re seeing a few of the eyes peeking between the legs there. If you scroll back up to the first image on the branch, she’s even visible there near the leg tips, out of focus. I suppose I might have to go hang the Tetragnatha corpse on the dog fennel, which is in bloom now, so she can catch something to eat.

The body length of my Tetragnatha specimen, eyes to abdomen tip, is around 11mm – the chelicerae alone are roughly 5mm folded. The legs at maximum stretch (meaning in the straight line hidey mode that lets them blend in with water reeds and twigs) may exceed 80mm – the forelegs alone are 52mm in length. Which means that enterprising tiny spiders like the one shown at right, only a millimeter in body length, can spin a web between the legs of a dead Tetragnatha as if it’s a tree, and come along for the ride when one is collected to serve as a photo subject. She’s still there, annoyed at how often I shifted her scaffolding to get better angles but otherwise unaffected. And yes, you’re seeing a few of the eyes peeking between the legs there. If you scroll back up to the first image on the branch, she’s even visible there near the leg tips, out of focus. I suppose I might have to go hang the Tetragnatha corpse on the dog fennel, which is in bloom now, so she can catch something to eat.

This is just showing off a few more pics from the Savannah et al trip, ones that didn’t fit into the text of the previous posts too well (I know – this implies I actually do some editing, which is startling in itself.) The problem is, all of them are vertical orientation, which is much harder to fit among the text, so the format is going to go wonky, or even wonkier than normal (since monitor resolutions are so variable, I just aim my layout for 1024 pixels wide and to hell with everyone else. Seriously, there’s no easy way to accommodate all the different formats out there and no reason to try.)

This is just showing off a few more pics from the Savannah et al trip, ones that didn’t fit into the text of the previous posts too well (I know – this implies I actually do some editing, which is startling in itself.) The problem is, all of them are vertical orientation, which is much harder to fit among the text, so the format is going to go wonky, or even wonkier than normal (since monitor resolutions are so variable, I just aim my layout for 1024 pixels wide and to hell with everyone else. Seriously, there’s no easy way to accommodate all the different formats out there and no reason to try.) On two mornings, an osprey (Pandion haliaetus) paid a visit to Our Hosts’ pond, perching for a short while in one of the taller trees overlooking the water before deciding that the human activity beneath was too unsettling. Here, I was getting my shots through gaps in the trees before coming out into the open, knowing how likely it was that the raptor would take flight when I did so. I’m fairly certain this is still a juvenile, from body shape and coloration not immediately apparent in this image – it’s likely this year’s brood. Shooting like this is tricky – it’s very important to at least keep the face and eyes clear of any obscuring vegetation, because even out of focus, it’ll produce a hazy patch that detracts from the sharpness of the eyes. You can see I just barely managed this in a small gap, with lots of places where the foliage blur can be seen. And it’s obvious that even in my position beneath the canopy, the osprey knows full well I’m down there, and took flight as soon as I came into the open. But I don’t think I could have asked for a better light angle.

On two mornings, an osprey (Pandion haliaetus) paid a visit to Our Hosts’ pond, perching for a short while in one of the taller trees overlooking the water before deciding that the human activity beneath was too unsettling. Here, I was getting my shots through gaps in the trees before coming out into the open, knowing how likely it was that the raptor would take flight when I did so. I’m fairly certain this is still a juvenile, from body shape and coloration not immediately apparent in this image – it’s likely this year’s brood. Shooting like this is tricky – it’s very important to at least keep the face and eyes clear of any obscuring vegetation, because even out of focus, it’ll produce a hazy patch that detracts from the sharpness of the eyes. You can see I just barely managed this in a small gap, with lots of places where the foliage blur can be seen. And it’s obvious that even in my position beneath the canopy, the osprey knows full well I’m down there, and took flight as soon as I came into the open. But I don’t think I could have asked for a better light angle. Still too cool in the morning for the insects to get started. The backlighting produces a nice outlining effect, but there’s another subtle thing at work too: notice how the background colors work to offset the dragonfly and butterfly, dark against the bright transparent wings and light against the near-silhouette of the butterfly. This is how a subtle change in position can help your subject stand out better.

Still too cool in the morning for the insects to get started. The backlighting produces a nice outlining effect, but there’s another subtle thing at work too: notice how the background colors work to offset the dragonfly and butterfly, dark against the bright transparent wings and light against the near-silhouette of the butterfly. This is how a subtle change in position can help your subject stand out better. Another alligator because, you know, gators. This was one of my attempts at throwing a little creativity at it (another can be seen in the rotating header images if you wait long enough.) If you want a good idea of scale, know that I could cover both eyes by cupping my hand across his head – well, if I was stupid. As small as this, he’d still have some serious teeth in that snout. My days working with wildlife occurred in North Carolina, not while I lived in Florida, though I wouldn’t have been averse to handling gators, with the right equipment of course. That, however, would only have been for rehabilitation and nuisance control reasons – healthy wild specimens not bothering anyone, like this one, need to be left alone. As do snakes, and bats, and groundhogs… they all live on this planet too. We can share.

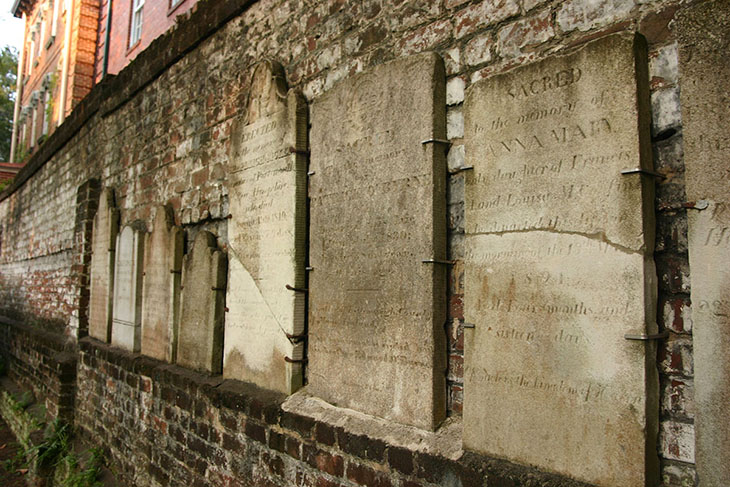

Another alligator because, you know, gators. This was one of my attempts at throwing a little creativity at it (another can be seen in the rotating header images if you wait long enough.) If you want a good idea of scale, know that I could cover both eyes by cupping my hand across his head – well, if I was stupid. As small as this, he’d still have some serious teeth in that snout. My days working with wildlife occurred in North Carolina, not while I lived in Florida, though I wouldn’t have been averse to handling gators, with the right equipment of course. That, however, would only have been for rehabilitation and nuisance control reasons – healthy wild specimens not bothering anyone, like this one, need to be left alone. As do snakes, and bats, and groundhogs… they all live on this planet too. We can share.  And finally, another image from Colonial Park Cemetery in downtown Savannah, this one being a ‘stacked’ or ‘HDR’ edit, blending the foreground in with the sky colors and the only clouds I had to work with throughout most of the trip. I made two exposures – one for the foreground details, one for the sky – and cut them together with no small amount of Photoshop work. Part of this was because I did not do what one should always do when intending such things, which is to take both exposures from exactly the same vantage with the camera locked onto a tripod – both exposures were handheld, and from slightly different camera positions. This meant, especially because I was using a wide-angle lens not terribly well corrected for distortion, that I needed to do a fair amount of stretching and distorting one of the images to get it to match the other in the areas of overlap. You can get some idea of the difference in exposure by looking at the lamps; the closest was taken from the sky exposure, but the others were from the ground exposure and are noticeably brighter, a bit blown out. I’m still pleased with the results, especially because the clouds have now imprinted the word “miasma” in my mind, but there’s a couple little detractors from the overall effect visible. Can you spot them?

And finally, another image from Colonial Park Cemetery in downtown Savannah, this one being a ‘stacked’ or ‘HDR’ edit, blending the foreground in with the sky colors and the only clouds I had to work with throughout most of the trip. I made two exposures – one for the foreground details, one for the sky – and cut them together with no small amount of Photoshop work. Part of this was because I did not do what one should always do when intending such things, which is to take both exposures from exactly the same vantage with the camera locked onto a tripod – both exposures were handheld, and from slightly different camera positions. This meant, especially because I was using a wide-angle lens not terribly well corrected for distortion, that I needed to do a fair amount of stretching and distorting one of the images to get it to match the other in the areas of overlap. You can get some idea of the difference in exposure by looking at the lamps; the closest was taken from the sky exposure, but the others were from the ground exposure and are noticeably brighter, a bit blown out. I’m still pleased with the results, especially because the clouds have now imprinted the word “miasma” in my mind, but there’s a couple little detractors from the overall effect visible. Can you spot them?

Long-jawed orb weavers (genus Tetragnatha) are a curious spider found most often – in my experience, anyway – on trees and reeds alongside water sources, but they also can be very fond of docks and boathouses. They have two outward appearances that are fairly distinctive, which is the pose at right when they’re out in their web over the water (you’re seeing a reflection of the sky in the water, since I’m aiming downwards,) or when threatened, they go to one of their web anchors and draw their legs into a straight line with their narrow bodies, blending into the thin leaves they live near. There are grassland varieties as well, but the aquatic-oriented species are the ones you’re most likely to see, and of course the one I captured here. There is a distinctive feature that they have, their namesake actually, which is only visible when you go in for close examination, and that’s the only warning that you get after the snarky way you opened the topic.

Long-jawed orb weavers (genus Tetragnatha) are a curious spider found most often – in my experience, anyway – on trees and reeds alongside water sources, but they also can be very fond of docks and boathouses. They have two outward appearances that are fairly distinctive, which is the pose at right when they’re out in their web over the water (you’re seeing a reflection of the sky in the water, since I’m aiming downwards,) or when threatened, they go to one of their web anchors and draw their legs into a straight line with their narrow bodies, blending into the thin leaves they live near. There are grassland varieties as well, but the aquatic-oriented species are the ones you’re most likely to see, and of course the one I captured here. There is a distinctive feature that they have, their namesake actually, which is only visible when you go in for close examination, and that’s the only warning that you get after the snarky way you opened the topic.

Here’s a better look at those chelicerae, the best I managed – my model was shot in situ with only some nudges to try and achieve a better angle, so conditions were a bit limiting. They’re still sufficient to see that the chelicerae are these studded war clubs of appendages, two big cans of whupass with easy-open tops (no, I did not learn my writing style from Shakespeare or Dickens, why do you ask?) While I would like to offer some insight into why Tetragnathas require such huge canines, I’m afraid I’m at a total loss, since their food consists of flimsy slow water flies that certainly don’t seem hard to subdue – perhaps their venom is especially weak so they have to beat their prey to death. As you ponder this, take note of the coloration on the chelicerae and lower ‘face,’ in the image above, continuing the theme from the abdomen and indicating that the carpet does match the drapes (yeah, I’m in one of those moods.)

Here’s a better look at those chelicerae, the best I managed – my model was shot in situ with only some nudges to try and achieve a better angle, so conditions were a bit limiting. They’re still sufficient to see that the chelicerae are these studded war clubs of appendages, two big cans of whupass with easy-open tops (no, I did not learn my writing style from Shakespeare or Dickens, why do you ask?) While I would like to offer some insight into why Tetragnathas require such huge canines, I’m afraid I’m at a total loss, since their food consists of flimsy slow water flies that certainly don’t seem hard to subdue – perhaps their venom is especially weak so they have to beat their prey to death. As you ponder this, take note of the coloration on the chelicerae and lower ‘face,’ in the image above, continuing the theme from the abdomen and indicating that the carpet does match the drapes (yeah, I’m in one of those moods.)

Eventually I met up with The Girlfriend and The Younger Sprog, who’d enjoyed the ghost tour – a different one than

Eventually I met up with The Girlfriend and The Younger Sprog, who’d enjoyed the ghost tour – a different one than  If you wanted proof that Savannah is the most haunted city in America, there you have it – the little spooks inhabit every grain of sand. I’m sure if you look hard enough you can find whatever kind of shape or face you want – I myself see an owl monkey, and a Tusken Raider (it’s subtle, but the joke is in there.) This is, of course, a simple optical effect, the flash’s light bouncing from reflective objects too close to be in focus, made more distinctive by a dark background – in optical terms, these are ‘circles of confusion.’ I’ve personally done it with mist, corn starch, soap bubbles, and now with glittery sand, and it’s more pronounced when the camera flash is very close to the lens (when the flash is further out, the sand/dust/whatever directly in front of the lens doesn’t get any light, since it passes above, and by the time they’re far enough away to be in the strobe beam, they’re in focus enough to be a tiny speck that’s usually ignored.) Focusing further out helps the effect, too, since close objects are further out of focus. Those that captured orbs on the tour might have caught dust, humidity, and possibly even something the guide provided. So yeah, “atmosphere…”

If you wanted proof that Savannah is the most haunted city in America, there you have it – the little spooks inhabit every grain of sand. I’m sure if you look hard enough you can find whatever kind of shape or face you want – I myself see an owl monkey, and a Tusken Raider (it’s subtle, but the joke is in there.) This is, of course, a simple optical effect, the flash’s light bouncing from reflective objects too close to be in focus, made more distinctive by a dark background – in optical terms, these are ‘circles of confusion.’ I’ve personally done it with mist, corn starch, soap bubbles, and now with glittery sand, and it’s more pronounced when the camera flash is very close to the lens (when the flash is further out, the sand/dust/whatever directly in front of the lens doesn’t get any light, since it passes above, and by the time they’re far enough away to be in the strobe beam, they’re in focus enough to be a tiny speck that’s usually ignored.) Focusing further out helps the effect, too, since close objects are further out of focus. Those that captured orbs on the tour might have caught dust, humidity, and possibly even something the guide provided. So yeah, “atmosphere…”

Places like the Georgia Sea Turtle Center also rehabilitate turtles injured by fishing gear, boat propellers, shark attacks, parasitic infestations, and even ingesting those ubiquitous goddamned plastic bags (which they mistake for jellyfish.)

Places like the Georgia Sea Turtle Center also rehabilitate turtles injured by fishing gear, boat propellers, shark attacks, parasitic infestations, and even ingesting those ubiquitous goddamned plastic bags (which they mistake for jellyfish.)

We headed north a short ways to St Simon’s Island, visible across the inlet from Jekyll, two of the many chunks of land separating the sea from the coastal wetlands that usually get the name “barrier islands.” There, we monkeyed around (seriously – I’m not showing you those pics) on a huge twisted old tree under the lighthouse, did a few portraits, and went for a swim in the inlet. I got some practice on my “block all the ugly unwanted details with foreground elements and cropping” techniques – the area surrounding the lighthouse was loaded with cars and signs – and I looked, once again in vain, for a decent place to do some snorkel explorations. We did the obligatory walk around the touristy areas of St Simon’s before heading back to Our Hosts’ Place outside of Savannah. Now, I probably could have amused myself for the week without leaving the property there, since they had a nearby pond with a lovely cypress swamp area, a beehive, and even some visitors (by now, you should know I’m not referring to humans with that.) They also had a Gator utility tractor that their dogs adored riding in, which we used for some exploring. The pond, alas, was too small to make an airboat viable – no southern swamps are complete without airboats.

We headed north a short ways to St Simon’s Island, visible across the inlet from Jekyll, two of the many chunks of land separating the sea from the coastal wetlands that usually get the name “barrier islands.” There, we monkeyed around (seriously – I’m not showing you those pics) on a huge twisted old tree under the lighthouse, did a few portraits, and went for a swim in the inlet. I got some practice on my “block all the ugly unwanted details with foreground elements and cropping” techniques – the area surrounding the lighthouse was loaded with cars and signs – and I looked, once again in vain, for a decent place to do some snorkel explorations. We did the obligatory walk around the touristy areas of St Simon’s before heading back to Our Hosts’ Place outside of Savannah. Now, I probably could have amused myself for the week without leaving the property there, since they had a nearby pond with a lovely cypress swamp area, a beehive, and even some visitors (by now, you should know I’m not referring to humans with that.) They also had a Gator utility tractor that their dogs adored riding in, which we used for some exploring. The pond, alas, was too small to make an airboat viable – no southern swamps are complete without airboats.

The Girlfriend’s Younger Sprog had never seen an American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) except in zoos, and that certainly doesn’t count, so we had to ensure that she saw one in the wild, and the Savannah National Wildlife Refuge is a pretty sure bet. Naturally, she had to show us all up by being the first to spot one, and the largest one at that – she had a rotten vantage point in the back seat on the grassland side of the drive instead of looking over the channel, and still found a beaut. Unfortunately, the height of the grass and decorum over approaching one weighing well over 90 kg (200 lbs) meant we have no really snazzy pics of that one, so what you see here is my meager find, whose head is as long as my blistered foot – just a leetle guy (it must be a male, since Our Female Host kept informing us that he was a Good Boy.) If you look close you can see minnows sharing the water alongside.

The Girlfriend’s Younger Sprog had never seen an American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) except in zoos, and that certainly doesn’t count, so we had to ensure that she saw one in the wild, and the Savannah National Wildlife Refuge is a pretty sure bet. Naturally, she had to show us all up by being the first to spot one, and the largest one at that – she had a rotten vantage point in the back seat on the grassland side of the drive instead of looking over the channel, and still found a beaut. Unfortunately, the height of the grass and decorum over approaching one weighing well over 90 kg (200 lbs) meant we have no really snazzy pics of that one, so what you see here is my meager find, whose head is as long as my blistered foot – just a leetle guy (it must be a male, since Our Female Host kept informing us that he was a Good Boy.) If you look close you can see minnows sharing the water alongside.

And so, slowly, I return to posting, revealing in the process that the last three posts were scheduled ahead of time to appear when they did, since we just spent a scant week in Savannah, Georgia with friends. We fit in most of what we’d aimed for; the primary exception, for me, was being unable to find any scorpions, something I’ve been longing to photograph for a while, and additionally motivated by the recent purchase of an ultra-violet flashlight. Scorpions fluoresce under UV,

And so, slowly, I return to posting, revealing in the process that the last three posts were scheduled ahead of time to appear when they did, since we just spent a scant week in Savannah, Georgia with friends. We fit in most of what we’d aimed for; the primary exception, for me, was being unable to find any scorpions, something I’ve been longing to photograph for a while, and additionally motivated by the recent purchase of an ultra-violet flashlight. Scorpions fluoresce under UV,

Now, there are two things that negatively affect sunset photography. The first, rather obviously, is overcast or stormy conditions. But the second is the polar opposite – skies that are too clear produce weak colors and no interesting cloud lighting or moody backgrounds. And unfortunately, the latter was what we had for our evening on Jekyll. While the light from the setting sun will go amber at least, seen here and in the opening image, to get the deep reds and purples that make for the groovy landscape shots takes significant humidity, and that just wasn’t present. I’ve said it before: nature photography takes a bit of luck in getting the right conditions – the skill part is knowing how to use them and being in the right place when they appear.

Now, there are two things that negatively affect sunset photography. The first, rather obviously, is overcast or stormy conditions. But the second is the polar opposite – skies that are too clear produce weak colors and no interesting cloud lighting or moody backgrounds. And unfortunately, the latter was what we had for our evening on Jekyll. While the light from the setting sun will go amber at least, seen here and in the opening image, to get the deep reds and purples that make for the groovy landscape shots takes significant humidity, and that just wasn’t present. I’ve said it before: nature photography takes a bit of luck in getting the right conditions – the skill part is knowing how to use them and being in the right place when they appear.  Perhaps the most-asked question from my photo students is about getting decent sunset images, because it’s actually a bit tricky. The camera’s exposure meter aims to produce

Perhaps the most-asked question from my photo students is about getting decent sunset images, because it’s actually a bit tricky. The camera’s exposure meter aims to produce  And then, I made a small mistake: I let Our Hosts book our suite without asking them where, exactly, we were staying. There wasn’t anything wrong in the slightest with our room – quite the contrary – but it meant I made no plans to be up at sunrise to chase more images, unaware that we were a short walk from the east shore of the island and ideally positioned for such pursuits. I woke early anyway, but didn’t venture out until the sky was fully light, to discover the beach so close. It meant that the light was much fiercer than preferred (again, pretty clear conditions,) but I still chased a few images anyway, joined a little later on by The Girlfriend and Our Female Host. There was some delay caused by camera lenses that had been sitting in air-conditioning overnight and were thus cool enough to attract condensation from the warm sea air, requiring several minutes to warm up and get clear. While you can wipe condensation away, it’ll return immediately until the glass temperature is right, and for dog’s sake don’t switch lenses in these conditions; condensation on inner surfaces, especially in a zoom or on the camera mirror, can take forever to clear. But while waiting, I used the fog as a soft-focus effect and tried a few shots anyway, with halfway-decent results. I admit to tweaking contrast slightly higher for the image at right.

And then, I made a small mistake: I let Our Hosts book our suite without asking them where, exactly, we were staying. There wasn’t anything wrong in the slightest with our room – quite the contrary – but it meant I made no plans to be up at sunrise to chase more images, unaware that we were a short walk from the east shore of the island and ideally positioned for such pursuits. I woke early anyway, but didn’t venture out until the sky was fully light, to discover the beach so close. It meant that the light was much fiercer than preferred (again, pretty clear conditions,) but I still chased a few images anyway, joined a little later on by The Girlfriend and Our Female Host. There was some delay caused by camera lenses that had been sitting in air-conditioning overnight and were thus cool enough to attract condensation from the warm sea air, requiring several minutes to warm up and get clear. While you can wipe condensation away, it’ll return immediately until the glass temperature is right, and for dog’s sake don’t switch lenses in these conditions; condensation on inner surfaces, especially in a zoom or on the camera mirror, can take forever to clear. But while waiting, I used the fog as a soft-focus effect and tried a few shots anyway, with halfway-decent results. I admit to tweaking contrast slightly higher for the image at right.

And to the right, an inset of the same image, contrast enhanced slightly. While The Girlfriend and I were shooting down amongst the driftwood, it seems Our Hosts and The Girlfriend’s Younger Sprog were trying to attract our attention from the pier – you can just make our Our Female Host waving. I hadn’t the faintest idea they were there, being only millimeters tall in the wide-angle lens I was using, and only discovered this a few days later when they asked if we’d seen them and I happened to check the images closely. Sorry about that, guys – I would have framed you against the sun had I known.

And to the right, an inset of the same image, contrast enhanced slightly. While The Girlfriend and I were shooting down amongst the driftwood, it seems Our Hosts and The Girlfriend’s Younger Sprog were trying to attract our attention from the pier – you can just make our Our Female Host waving. I hadn’t the faintest idea they were there, being only millimeters tall in the wide-angle lens I was using, and only discovered this a few days later when they asked if we’d seen them and I happened to check the images closely. Sorry about that, guys – I would have framed you against the sun had I known.