While I had been planning to put this post up soon, Dr. Jerry Coyne over at Why Evolution Is True beat me to it with his own post about snakes, but his includes some great video, including a stunning sequence of an egg-eating snake! I hate it when someone on my blogroll to the right upstages me, even before I actually post! Although he’s a university professor and author, so I suppose that has privileges…

For some unknown reason, I have seen surprisingly few snakes this year, which is annoying to someone that likes snakes as much as I do. My property, which plays host to as many different animals as it does (including some resident treefrogs in a potted plant,) does not seem to cater to snakes. Now just a few days ago, as we get late into the season and the days are starting to get chilly, I glanced down at the base of a tree at The Girlfriend’s house and spotted a short length of bicycle chain, or at least that was the immediate impression, soon replaced with one of recognition at the pattern of a young black rat snake.

Black rat snakes (Elaphe obsoleta obsoleta,) despite their scientific name, are very common throughout the eastern United States, and one of the largest you’re likely to encounter, at times reaching over two meters (six feet.) They’re great tree climbers, great everything climbers, and can even be found nesting in attics. As adults, they resemble little more than black garden hoses, having the same diameter and often seen “discarded” casually in the grass. Their white undersides aren’t usually apparent unless you pick them up, which is easier to do than you might imagine, since they are typically fairly docile.

The pattern of the young differentiates greatly. Their patchwork pattern of black spots on a medium-pale grey base makes many people think they are entirely unrelated, not helped by the size they are for their early years. This pattern helps them remain camouflaged while they are at this vulnerable size, since it blends very well against tree bark and in shady patches. And like many snakes, they usually become motionless when danger threatens, opting to avoid attracting attention rather than bolting for cover, which is what allowed me to capture this one.

Their diet consists of just about everything, including the namesake rats. But they also eat birds, eggs, and even other snakes if the pickings are slim. They’re constrictors, with a completely harmless bite, and their tiny teeth are good only for holding prey. Even if you manage to get one to bite you, you’ll display little more than tiny pinpricks of blood, not an honorable wound at all for intrepid Crocodile Hunters. I have used perfectly wild Black Rat Snakes for educational talks, because they are so easy to handle, but do not recommend retaining any wild animal as a pet. Not simply because they don’t belong and have drives to be outdoors rather than a small cage, but also because of the damage that can be done to them by poor diet and improper housing.

In the right conditions, the adults can be seen to retain vestiges of the patterns they had as young-uns, between their scales, but you typically have to look hard to see this at all. This example, of one roughly 1.5 meters (5 ft,) shows the pattern in bright sunlight, right there in the middle, as it heads straight up a tree. You might think they do this slowly, but you’d be amazed – they can scale a vertical rough surface at the same speed as their casual

In the right conditions, the adults can be seen to retain vestiges of the patterns they had as young-uns, between their scales, but you typically have to look hard to see this at all. This example, of one roughly 1.5 meters (5 ft,) shows the pattern in bright sunlight, right there in the middle, as it heads straight up a tree. You might think they do this slowly, but you’d be amazed – they can scale a vertical rough surface at the same speed as their casual gate gait [cripes] on the ground (I suppose it’s improper to use “gategait” on something with no legs, but you know what I mean.)

In spring and fall, they can be seen in early mornings on the roads, or occasionally sidewalks. As “cold-blooded” (ectothermic) animals, they get heat from their environment, but when the nights are cold this makes them a bit sluggish. Since they often hunt at night, this can pose a problem to digestion, so they drape their wonderfully solar-absorbent bodies in areas to capture the maximum amount of warmth when the sun rises – unfortunately, this leads to many of the encounters they have with humans, in which they rarely come out unscathed. It’s a shame, since they’re simply doing their own thing and fitting in nice and snugly with the ecosystem.

I’ve encountered black rat snakes rather suddenly on a large number of occasions, sometimes in surprisingly close quarters. Doing animal rescue work years ago meant (as one of the people who had no qualms about snake handling) that I got many of the snake calls, and have removed them from attics, downspouts, front lawns, schools, and once the sidewalk in front of the public transit garage – where it had kept half the staff clustered inside against the glass door as it digested its bird meal. A few tried bluff displays, one actually struck – again, big deal. They honestly can’t do any damage. Mostly, they retreat, and in situations where they’re out in the open and suspect they’re in view, they can pull backwards with glacial slowness, hardly appearing to move at all, so as not to attract attention if they haven’t yet been noticed. Many species of animal, humans included, can miss the obvious simply because it’s not moving – I’ve spotted a black rat snake hanging out of a downspout on a porch, a few meters behind someone I was conversing with. They might have missed it entirely had I not pointed it out.

Like many snakes, they have a warning display when agitated, which is vibrating their tail madly – rattlesnakes only have a handy noisemaker, but they’re not the only ones to do this. When the tail encounters dry leaves the sound is fantastic, but even on a smooth surface the buzzing is neat. Coupled with a writhing coiled motion (see one of Dr. Coyne’s videos linked above,) it looks very ominous, but the threat from snakes in North America is way over-emphasized. Telling the venomous species apart is fairly easy – it simply means you have to look close at markings and memorize them. Even without this effort, leaving them be works fine; pushing them off with a broom, if they’re in a hazardous area, is usually sufficient. No snake can eat a human, so they only want to be left alone – you’re the threat, not them. The phobia many people have over snakes is a human failing, not the snakes’ fault, and no, it is not inherent or instinctual, it’s usually conditioned by culture. Get over it. Snakes are all around us, and by a large margin not even remotely dangerous. Get this: I actively hunt out snakes, know how to spot them and how to handle them, and still haven’t had an encounter with a venomous species in the wild, save for rescue calls (which were notoriously uneventful.)

Yes, I’ve heard the stories of people being pursued aggressively by venomous snakes, just like I’ve heard the stories of people curing their illnesses with crystals or homeopathic remedies. They’re the same level of total bullshit. The people who have to capture and handle these same venomous snakes as a matter of routine will tell you how unfounded the stories of aggression are. It’s all defense at provocation, nothing more.

My little buddy here, despite displaying a defensive coiled-and-ready-to-strike posture (when I did not have the camera handy,) never even attempted to strike, and was easy to handle. The pic below gives a fairly good indication of size. The Girlfriend, who really doesn’t like snakes, even thought it was cute.

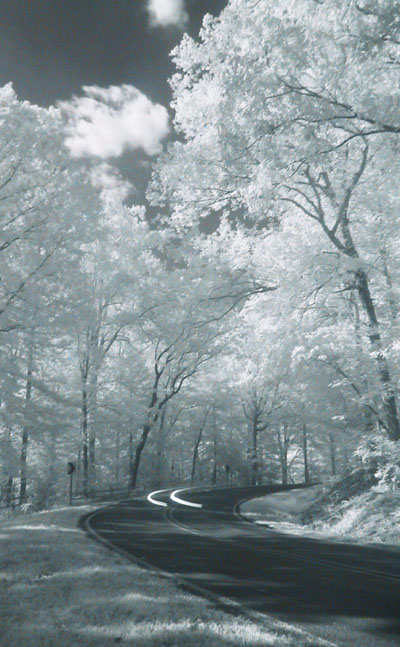

From time to time, I play around with infra-red photography, because it can produce some really cool effects, and also because there are ways to make it relatively easy. An old digital camera of mine, the

From time to time, I play around with infra-red photography, because it can produce some really cool effects, and also because there are ways to make it relatively easy. An old digital camera of mine, the

See the red line by the “4” on this focusing ring? That’s the IR pointer. Once focused without the filter in place, you then shift the focus ring from its alignment with the center pointer (here, pointing at the back of the “5”) to line up instead with the IR pointer. You can’t trust autofocus in most cases because the IR filters don’t let through enough light for the sensor to get a decent contrast reading. The Pro90 can achieve autofocus, but it struggles with the 750nm filter, and is very balky with the 950nm filter – conditions have to be very bright and contrasty for it to lock on.

See the red line by the “4” on this focusing ring? That’s the IR pointer. Once focused without the filter in place, you then shift the focus ring from its alignment with the center pointer (here, pointing at the back of the “5”) to line up instead with the IR pointer. You can’t trust autofocus in most cases because the IR filters don’t let through enough light for the sensor to get a decent contrast reading. The Pro90 can achieve autofocus, but it struggles with the 750nm filter, and is very balky with the 950nm filter – conditions have to be very bright and contrasty for it to lock on.

Another image that I caught shows off the lovely fawn coloration of their heads a bit more, as well as the red patch at the nape of the neck and the pointed tips of the tail feathers. Most woodpeckers use their tail as a brace and springboard for pecking, so the shafts of those feathers are likely quite strong. The breast feathers, with their spots, are very distinctive even when found by themselves on the floor of the forest. They’re fan-shaped for maximum coverage and heat retention, so rather than each spot belonging to only one feather, every feather has a collection of them – you’re seeing fewer feathers here than you might imagine.

Another image that I caught shows off the lovely fawn coloration of their heads a bit more, as well as the red patch at the nape of the neck and the pointed tips of the tail feathers. Most woodpeckers use their tail as a brace and springboard for pecking, so the shafts of those feathers are likely quite strong. The breast feathers, with their spots, are very distinctive even when found by themselves on the floor of the forest. They’re fan-shaped for maximum coverage and heat retention, so rather than each spot belonging to only one feather, every feather has a collection of them – you’re seeing fewer feathers here than you might imagine. Eastern Yellowjackets (Vespula maculifrons) are generally ground-nesting wasps, known to be the most aggressive in the area. Disturbing the nest, which is usually an unobtrusive hole in the ground, can cause them to swarm, and most especially so if you kill one of their number, which releases a scent that alerts the others. I have run afoul of this before, being stung over a dozen distinctive times in a frenetic couple of minutes. The advice is, “Don’t slap them,” but this is a bit hard to follow as they’re stinging you. Unlike honeybees, yellowjackets do not lose the embedded stinger on the first sting, but can nail you repeatedly. As I discovered then, spit on and clean off the spot where you smooshed one before it attracts more to the exact same spot. The stings can start itching madly at odd times for several days after the attack, by the way…

Eastern Yellowjackets (Vespula maculifrons) are generally ground-nesting wasps, known to be the most aggressive in the area. Disturbing the nest, which is usually an unobtrusive hole in the ground, can cause them to swarm, and most especially so if you kill one of their number, which releases a scent that alerts the others. I have run afoul of this before, being stung over a dozen distinctive times in a frenetic couple of minutes. The advice is, “Don’t slap them,” but this is a bit hard to follow as they’re stinging you. Unlike honeybees, yellowjackets do not lose the embedded stinger on the first sting, but can nail you repeatedly. As I discovered then, spit on and clean off the spot where you smooshed one before it attracts more to the exact same spot. The stings can start itching madly at odd times for several days after the attack, by the way… Should I have really wanted lots of detail shots of an insect in flight, this is the wrong way to go about it – the depth-of-field is way too short and the area for the wasps to be in too large. To control this, some insect photographers set up a rig where two infrared or laser beams cross at a particular point. These beams are linked to light sensors and into a device to trip the camera shutter – both beams have to be broken to fire the camera, so the insect has to be in a precise location. Since this is still unimaginably hard to achieve in three-dimensional space, another factor is occasionally added: a tube that empties out right near the crossed beams, just outside of the camera’s view. Insects are introduced into this tube and gently blown along it to exit by the crossed beams, so that they stand a much greater chance of passing through the key focus point. This is how the studies of insects in flight are often done. When time is money, you do whatever you can to increase the odds. As I’ve shown at top, you can indeed catch insects in flight without special rigs, but you’ll notice the shadow behind the wasp – it was barely airborne at this point, and I shot 86 frames trying for this, with only a handful of sharp images.

Should I have really wanted lots of detail shots of an insect in flight, this is the wrong way to go about it – the depth-of-field is way too short and the area for the wasps to be in too large. To control this, some insect photographers set up a rig where two infrared or laser beams cross at a particular point. These beams are linked to light sensors and into a device to trip the camera shutter – both beams have to be broken to fire the camera, so the insect has to be in a precise location. Since this is still unimaginably hard to achieve in three-dimensional space, another factor is occasionally added: a tube that empties out right near the crossed beams, just outside of the camera’s view. Insects are introduced into this tube and gently blown along it to exit by the crossed beams, so that they stand a much greater chance of passing through the key focus point. This is how the studies of insects in flight are often done. When time is money, you do whatever you can to increase the odds. As I’ve shown at top, you can indeed catch insects in flight without special rigs, but you’ll notice the shadow behind the wasp – it was barely airborne at this point, and I shot 86 frames trying for this, with only a handful of sharp images.

The thing is, none of the concepts does anything to explain why we find such measurements pleasing to the eye (or, in some cases, ear or touch.) The various mathematical formulas were created to match (more or less) this very common tendency for humans to respond to certain layouts, but it’s clear we’re not concerned with the exact numbers. There is something fundamental at work deep in our minds. I originally toyed with the idea that our two eyes were the culprit, having something to do with visual range, overlap, and our desire to assess surroundings. A subject right smack in front of you gains all of your attention, but can be threatening, while one offset allows you room to see something else, to escape, and so on. Sounded good, but it failed to explain vertical compositions, and would likely have led to a dislike of them entirely if it were true. Pop psychology is rarely useful ;-)

The thing is, none of the concepts does anything to explain why we find such measurements pleasing to the eye (or, in some cases, ear or touch.) The various mathematical formulas were created to match (more or less) this very common tendency for humans to respond to certain layouts, but it’s clear we’re not concerned with the exact numbers. There is something fundamental at work deep in our minds. I originally toyed with the idea that our two eyes were the culprit, having something to do with visual range, overlap, and our desire to assess surroundings. A subject right smack in front of you gains all of your attention, but can be threatening, while one offset allows you room to see something else, to escape, and so on. Sounded good, but it failed to explain vertical compositions, and would likely have led to a dislike of them entirely if it were true. Pop psychology is rarely useful ;-)