I had actually planned to have a post regarding the summer solstice pop up Sunday, nothing elaborate, but at least containing current photos, but then life happened in the form of emergency surgery. No, not for me, but for The Girlfriend’s Sprog who, in a fit of impetuous infection, callously threw away her plans to retain her appendix throughout her life. She’s fine, but we have confirmed that she doesn’t come out of anesthesia well.

I had actually planned to have a post regarding the summer solstice pop up Sunday, nothing elaborate, but at least containing current photos, but then life happened in the form of emergency surgery. No, not for me, but for The Girlfriend’s Sprog who, in a fit of impetuous infection, callously threw away her plans to retain her appendix throughout her life. She’s fine, but we have confirmed that she doesn’t come out of anesthesia well.

Monday’s color post had been written weeks back and simply scheduled to appear – I haven’t been logged into WordPress since early Saturday morning. So briefly, I’ll mention the little girl seen here, an Eastern box turtle (Terrapene carolina carolina) that I discovered Sunday struggling in the pond in the backyard; this is notable in that it is a terrestrial, tortoise species that is not aquatic and thus not at home in water that’s 30cm deep and more. Which means my happening along was probably fortuitous, because she couldn’t climb out and was unable to tread water for very long. Despite the gratitude she should ethically have bestowed upon me, she was reluctant to pose for portraits, especially where the light was ideal.

This was clearly a female, about ten years old or so, determined by the brown eyes, the lack of a deep indent on the plastron (the bottom shell,) and the ridges on each scute (the textured pattern of the carapace, or upper shell.) She was likely seeking hydration in the hot weather, so I’m going to have to put a log or something into the pond to assist escapes.

While retrieving her, I also spotted a frog submerging in the pond, and sat down after the turtle portraits to wait out the frog’s re-emergence. It did so only briefly, and not in a position where I could identify the species accurately, so this will remain a project for later. The pine straw seen here is ubiquitous in the yard, requiring daily removal from the pond, while the discoloration of the water is courtesy of the rains from a few days ago carrying in silt from the red clay – it will take days to settle out, and is one of the reasons why snorkeling in North Carolina is well-nigh pointless. Soon after this image was taken, The Girlfriend’s Younger Sprog said that she thought she should see a doctor, which sparked a 26-hour adventure. We’re going to ignore her next time she says that…

While retrieving her, I also spotted a frog submerging in the pond, and sat down after the turtle portraits to wait out the frog’s re-emergence. It did so only briefly, and not in a position where I could identify the species accurately, so this will remain a project for later. The pine straw seen here is ubiquitous in the yard, requiring daily removal from the pond, while the discoloration of the water is courtesy of the rains from a few days ago carrying in silt from the red clay – it will take days to settle out, and is one of the reasons why snorkeling in North Carolina is well-nigh pointless. Soon after this image was taken, The Girlfriend’s Younger Sprog said that she thought she should see a doctor, which sparked a 26-hour adventure. We’re going to ignore her next time she says that…

So, on to the travels and travails of Jim Kramer, the official Walkabout Noncontiguous Noncorrespondent. As is required by law when visiting Alaska (punishable by three years astonished disbelief from friends when told you didn’t go,) Jim went out on a whale-watching trip in [Al: fill in proper name here before posting] Bay. And, judging from the images, photographing whales is as tricky as photographing dolphins.

Everyone, naturally, thinks of whale watching by imagining a humpback whale breaching majestically a good eight meters out of the water before crashing back down in a mini-tsunami, usually while hearing the trumpets of the Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom theme* (which seems to be unavailable everywhere I look so I can’t provide an example for you young whippersnappers.) Such behavior, however, is rare, and normal activities of cetaceans consists of brief appearances to accommodate the necessity of breathing – the top of the head, where the blowhole is located, is usually what is seen, and then only long enough to exhale and inhale again.

Here, an orca (Orcinus orca), more commonly known by the misleading name of killer whale, produces a noticeable spray from having water still present over or in the blowhole when it exhaled. If they’re anything like the Atlantic bottlenose dolphins that they’re related to, they appear unpredictably, meaning one has to be scanning the empty water for the faintest signs and quickly bring the camera to bear when they appear, with luck nailing the focus within a second. Nice portraits are challenging, to say the least.

I’m glad to see I’m not the only one who doesn’t instinctively keep the camera body level – maybe that’s a thing with Canon bodies and/or the additional battery packs – but at least I correct and re-crop them before posting…

I don’t have to ask Jim what species these are, because it’s obvious – not just from the color pattern above, but from the distinctively-shaped dorsal fin, which seems to droop only when retained in captivity. Jim was lucky enough to see several families it appears, and you have not missed the mist in the air from the recent exhalation, right?

However, the first of Jim’s images, above, I’m fairly certain is not an orca, but a whale’s pectoral fin instead – my guess is a humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae,) but this is only a guess based on just a handful of images and the knowledge that they frequent the area. Originally, the change in light conditions and species led me to believe that they were photographed with some separation, but the time stamps are intermixed with the orcas above, which means so much for my judgment. The image below remains my favorite, and also clear evidence we’re not dealing with orcas since they have vertical tails. [No they don’t – what the hell made me say that?]

Speaking of light conditions, pay attention to the drastic difference in appearance with the next two images, which are the same subject.

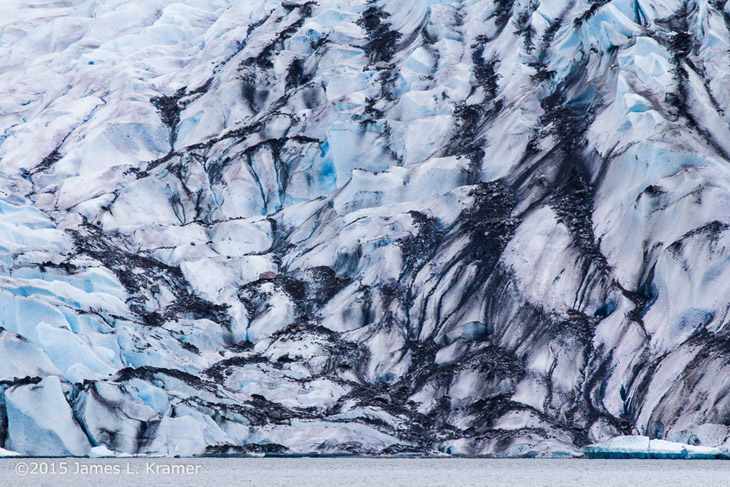

From the artistic standpoint anyway, I like this image better than the one below, largely for the contrast of colors, but the composition is pretty solid too, especially given that it was taken from a tour boat where control over positioning could only be achieved with timing. Personally, I’d love to take a kayak out into conditions like this, but the risk to the camera equipment is pretty high. I mean, I could survive a dunking easily, but even the humidity and spray could trash a body and lens.

These are California sea lions (Zalophus californianus,) not to be confused with seals, which are actually a different classification of pinniped – look for the ear flaps, just barely visible here, and the orientation of the hind flippers to tell them apart. Or if it’s noisy, it’s a sea lion. But anyway, notice the difference in color and lighting compared to the one above, especially the color of the fur and of the water. Mostly, this is due to changing position between the two, switching the angle from which the sun is coming at the sea lions and the water, but likely also due to the varying cloud conditions, which thinned a bit for the second image while not actually allowing direct sunlight to come through. Thus the shadows remain soft and contrast manageable, but the latter image doesn’t give the deep overcast impression of the former. While you might suspect the exposure meter of the camera had its say in the matter, there’s only 1/3rd stop difference between the two – it’s definitely the light.

By the way, as ragged as it looks, the condition of the fur is typical, and not indicative of illness or injury. The topmost sea lion, meanwhile, sports what I call the “chute didn’t open” pose, usually associated with sleeping cats.

Jim got extremely lucky with the next one, in capturing the elusive Alaskan man o’ war, the rare arctic version of the dangerous jellyfish/siphonophore found in tropical waters, vastly bigger than its warm water cousin.

Okay, not really, I’m just foolin’. They’re actually pretty common.

* Seriously, there was this great triumphant, um, trumpet theme, a very distinctive fourteen-note volley, but the show dates from before video recorders and so few people would have a sample of it. It does not seem to have made it to any of the much-later DVDs and reboots, so I’m guessing the producers never secured the rights to it for subsequent use.

I had actually planned to have a post regarding the summer solstice pop up Sunday, nothing elaborate, but at least containing current photos, but then life happened in the form of emergency surgery. No, not for me, but for The Girlfriend’s Sprog who, in a fit of impetuous infection, callously threw away her plans to retain her appendix throughout her life. She’s fine, but we have confirmed that she doesn’t come out of anesthesia well.

I had actually planned to have a post regarding the summer solstice pop up Sunday, nothing elaborate, but at least containing current photos, but then life happened in the form of emergency surgery. No, not for me, but for The Girlfriend’s Sprog who, in a fit of impetuous infection, callously threw away her plans to retain her appendix throughout her life. She’s fine, but we have confirmed that she doesn’t come out of anesthesia well.

While retrieving her, I also spotted a frog submerging in the pond, and sat down after the turtle portraits to wait out the frog’s re-emergence. It did so only briefly, and not in a position where I could identify the species accurately, so this will remain a project for later. The pine straw seen here is ubiquitous in the yard, requiring daily removal from the pond, while the discoloration of the water is courtesy of the rains from a few days ago carrying in silt from the red clay – it will take days to settle out, and is one of the reasons why snorkeling in North Carolina is well-nigh pointless. Soon after this image was taken, The Girlfriend’s Younger Sprog said that she thought she should see a doctor, which sparked a 26-hour adventure. We’re going to ignore her next time she says that…

While retrieving her, I also spotted a frog submerging in the pond, and sat down after the turtle portraits to wait out the frog’s re-emergence. It did so only briefly, and not in a position where I could identify the species accurately, so this will remain a project for later. The pine straw seen here is ubiquitous in the yard, requiring daily removal from the pond, while the discoloration of the water is courtesy of the rains from a few days ago carrying in silt from the red clay – it will take days to settle out, and is one of the reasons why snorkeling in North Carolina is well-nigh pointless. Soon after this image was taken, The Girlfriend’s Younger Sprog said that she thought she should see a doctor, which sparked a 26-hour adventure. We’re going to ignore her next time she says that…

Since it is now ‘officially’ summer, we will perversely jump back to almost the only color to be found in wintertime, holly berries in full fruit against the brilliant green of the leaves and a rich blue sky. I will admit to being quite pleased that we can find skies like this throughout North Carolina winters; having grown up in central New York, the winters there spelled overcast conditions for the majority of the time, which could be very depressing. The few occasions when skies like this appeared, it often spelled a wicked cold front coming through and, instead of being pleasant, it was bitterly cold and windy. The decision to get the fuck out of the state came on one such day, when our water pump had failed and I was in our shack of a wellhouse trying to get it operational again in wind chill conditions down below 0°f. It’s very easy to start asking questions like, “What am I doing here?” in circumstances like that.

Since it is now ‘officially’ summer, we will perversely jump back to almost the only color to be found in wintertime, holly berries in full fruit against the brilliant green of the leaves and a rich blue sky. I will admit to being quite pleased that we can find skies like this throughout North Carolina winters; having grown up in central New York, the winters there spelled overcast conditions for the majority of the time, which could be very depressing. The few occasions when skies like this appeared, it often spelled a wicked cold front coming through and, instead of being pleasant, it was bitterly cold and windy. The decision to get the fuck out of the state came on one such day, when our water pump had failed and I was in our shack of a wellhouse trying to get it operational again in wind chill conditions down below 0°f. It’s very easy to start asking questions like, “What am I doing here?” in circumstances like that.

I used the word, “precipitous,” in the teaser, and anyone that knows me can tell you that I don’t use that word lightly. Juneau is an area of ridiculously vertical landscapes, as are quite a few portions of Alaska – not a place where Frisbees are popular, I’m betting. But you can probably hang-glide to Seattle…

I used the word, “precipitous,” in the teaser, and anyone that knows me can tell you that I don’t use that word lightly. Juneau is an area of ridiculously vertical landscapes, as are quite a few portions of Alaska – not a place where Frisbees are popular, I’m betting. But you can probably hang-glide to Seattle…

And then, the rains did come.

And then, the rains did come.

Spiders most often seek shelter, usually at one of the upper anchors of the web, but will resume position quickly, sometimes gathering drops that adhere to their bodies as they do so, though whether this is intentional to make it easy to drink, or incidental as they clamber past, is something I haven’t determined yet (and quite possibly won’t – who could tell if a spider is snagging dewdrops intentionally as it crawls across its web?) I have seen some spiders purposefully dislodging drops from the web, presumably to keep it invisible, while others seem to ignore it in the knowledge that it will evaporate quickly. Actually, there is probably no such knowledge – they just never evolved an instinct to worry about it because it never affected their survival. Let’s not credit too much cognition to the class.

Spiders most often seek shelter, usually at one of the upper anchors of the web, but will resume position quickly, sometimes gathering drops that adhere to their bodies as they do so, though whether this is intentional to make it easy to drink, or incidental as they clamber past, is something I haven’t determined yet (and quite possibly won’t – who could tell if a spider is snagging dewdrops intentionally as it crawls across its web?) I have seen some spiders purposefully dislodging drops from the web, presumably to keep it invisible, while others seem to ignore it in the knowledge that it will evaporate quickly. Actually, there is probably no such knowledge – they just never evolved an instinct to worry about it because it never affected their survival. Let’s not credit too much cognition to the class.

One little surprise appeared the other sweltering night, spotted on the downspout just after I misted the plants below, so I provided its own misting. This is likely a Copes grey treefrog (Hyla chrysoscelis) and they need the moisture, so it’s rare to see them out when it’s been so dry. Just to demonstrate my dudeness, not only did I provide a decent soaking, I turned on the deck light right overhead and left it on for a few hours in an attempt to provide more food for the little spud.

One little surprise appeared the other sweltering night, spotted on the downspout just after I misted the plants below, so I provided its own misting. This is likely a Copes grey treefrog (Hyla chrysoscelis) and they need the moisture, so it’s rare to see them out when it’s been so dry. Just to demonstrate my dudeness, not only did I provide a decent soaking, I turned on the deck light right overhead and left it on for a few hours in an attempt to provide more food for the little spud. This little stowaway couldn’t be much larger than 1mm in body length, and by flashlight it remained hard to make out, though it could be seen perambulating around on Mt Frog here. If you look closely, you can see that it has its own supply of water, a tiny droplet adhering to its leg. But in a moment, it turned to face me, and the resulting tight crop confirmed what the other images had hinted at.

This little stowaway couldn’t be much larger than 1mm in body length, and by flashlight it remained hard to make out, though it could be seen perambulating around on Mt Frog here. If you look closely, you can see that it has its own supply of water, a tiny droplet adhering to its leg. But in a moment, it turned to face me, and the resulting tight crop confirmed what the other images had hinted at.

As the storm started to settle down a bit, I could start using the timing trick; lightning seems to follow a rough pattern, with a certain amount of time between strikes occurring from the same area of cloud. Count off the seconds between strikes, then lock the shutter open about ten seconds before that time is reached again. Like I said, its rough, and it’s entirely possible that it’s merely my own confirmation bias and the strikes are more random than that – I’d need to keep some pretty specific records to be sure either way. But this image here is a successful attempt, at least. I didn’t want the amber glow from the city lights in the clouds, so the only way to accomplish that is with a short exposure that captures a flash at just the right moment, and this one was a seven-second exposure timed for the reappearance of the flash. I’m pleased.

As the storm started to settle down a bit, I could start using the timing trick; lightning seems to follow a rough pattern, with a certain amount of time between strikes occurring from the same area of cloud. Count off the seconds between strikes, then lock the shutter open about ten seconds before that time is reached again. Like I said, its rough, and it’s entirely possible that it’s merely my own confirmation bias and the strikes are more random than that – I’d need to keep some pretty specific records to be sure either way. But this image here is a successful attempt, at least. I didn’t want the amber glow from the city lights in the clouds, so the only way to accomplish that is with a short exposure that captures a flash at just the right moment, and this one was a seven-second exposure timed for the reappearance of the flash. I’m pleased.

This is just a tiny preview of posts yet to come – I think. I’ve learned not to bank on such things now, but we’re off to a good start, anyway. It’s likely to get a bit more precipitous around here.

This is just a tiny preview of posts yet to come – I think. I’ve learned not to bank on such things now, but we’re off to a good start, anyway. It’s likely to get a bit more precipitous around here. It’s been a long time since the

It’s been a long time since the