Near sunset yesterday the thunderstorms rolled in, with conditions too bright to do any time exposures, and after two hailstorms, the rains came again. It’s only been a week since the last, but with sweltering weather that’s causing the plants to wilt in between, and watching the level in the rain barrel declining drastically, it’s something I pay attention to. However, the day after the last we’d installed a second rain barrel, and they’re both brimming now, so it’s good.

The Girlfriend’s Younger Sprog pointed out the visible structure of one of the hailstones we picked up, and I saved it in the freezer for a quick photo illustration, done today when the temperature had returned to “steamy,” so it was melting rapidly as I got the shots, but it still illustrated the layered nature of the stone, less than a centimeter across at this point.

The first storm deposited ice pellets slightly bigger than candies, but the second one following less than an hour behind dropped misshapen, ugly chunks up to 3 cm across, twisted and gnarled – I’ve never seen anything like it.

After the rain and the sunset, the critters came out to play, notably the treefrogs. The Copes grey treefrogs (Hyla chrysoscelis) were calling enthusiastically, one from the region of the backyard, so of course I had to go out and find it. While it stopped calling as my light approached, it got suckered into a false sense of security when I shut the light off and stood still for a few minutes. I’d suspected it was near the pond, and with a loud creeeeek it revealed itself on the fence immediately adjacent, quite a small specimen.

At higher magnification, the peculiar swollen shape of the toe pads is more visible, but if you look carefully you can see the toes of the farther (right) foreleg are actually propped up on a spiderweb – yes, they’re very long and attenuated. The ubiquitous pine needles can be seen adhering to the wet fence slat behind it, to give an idea of scale – I’d estimate this one to be no more than 4 cm, not much bigger than the gnarly hail.

More calls were coming from the cattail-bearing ditch alongside the main road nearby, so I naturally checked that out too. There were several in the low branches of a tree right above the ditch, calling exuberantly, though they typically halted as the light struck them, so getting an image of one in mid-croak, as this one is, took a few attempts. It would have been an amusing spectacle, as well: the ground sloped sharply directly under the tree, and as I was trying for a good vantage I would attempt to be higher up the slope, which was extremely slippery. With care and patience I would achieve a stable position, but then I’d raise the camera and shift my balance, often as not abruptly losing my footing and doing that sudden eruption of flailing arms at odd angles in an attempt to maintain balance. This was punctuated by both a headlamp and a focusing light on the camera, which would also thrash around in all directions. It must have looked great…

More calls were coming from the cattail-bearing ditch alongside the main road nearby, so I naturally checked that out too. There were several in the low branches of a tree right above the ditch, calling exuberantly, though they typically halted as the light struck them, so getting an image of one in mid-croak, as this one is, took a few attempts. It would have been an amusing spectacle, as well: the ground sloped sharply directly under the tree, and as I was trying for a good vantage I would attempt to be higher up the slope, which was extremely slippery. With care and patience I would achieve a stable position, but then I’d raise the camera and shift my balance, often as not abruptly losing my footing and doing that sudden eruption of flailing arms at odd angles in an attempt to maintain balance. This was punctuated by both a headlamp and a focusing light on the camera, which would also thrash around in all directions. It must have looked great…

I had thoughtfully brought along the voice recorder, so I did a few recordings of the frogs sounding off, one of which was in a branch directly overhead, maybe a meter from the recorder. To get a real feel for it, boost your volume up a bit – the call should almost make you wince.

My favorite photo remains this one, however, taken before another graceless skid down the incline.

There were other critters out taking advantage of the humidity as well – the cattails in the ditch sported a variety of insects, including more mantids and this lesser meadow katydid nymph (genus Conocephalus.) It’s easy to mistake it for a grasshopper – I did, anyway – mostly because they’re closely related. You’ll see more of this species – kinda – shortly.

I took another quick trip across to the local pond, spotting several bullfrogs and an untold number of long-jawed orb weavers, spurred into action by the recognition that the rain would produce more flying insect activity as well. It’s also been a very good season for mantids, which can be found everywhere. This minuscule specimen was parading proudly on another patch of cattails, different from the previous.

Observing the mist rising from the waters of the pond by the light of a half-moon, I went back and got the tripod to do a few time exposures. While I didn’t get anything exciting, and the low-lying steam can only faintly be made out, I did at least capture a firefly in the frame, the streak faintly visible against the sky – one of these days I’ll have to go to a location where they’re very active and do some more long-exposure shots. This one also captured a bit of depth among the background trees – other frames rendered them more of a single-plane silhouette. The green glow from the right is evidence of a mercury street lamp, the kind that are blue to our eyes. Even when I can selectively block the bulb itself from appearing in the frame, it’s hard to eradicate the light spilling from them. I’ll just have to locate a pond without any nearby lights, which could be a challenge.

Observing the mist rising from the waters of the pond by the light of a half-moon, I went back and got the tripod to do a few time exposures. While I didn’t get anything exciting, and the low-lying steam can only faintly be made out, I did at least capture a firefly in the frame, the streak faintly visible against the sky – one of these days I’ll have to go to a location where they’re very active and do some more long-exposure shots. This one also captured a bit of depth among the background trees – other frames rendered them more of a single-plane silhouette. The green glow from the right is evidence of a mercury street lamp, the kind that are blue to our eyes. Even when I can selectively block the bulb itself from appearing in the frame, it’s hard to eradicate the light spilling from them. I’ll just have to locate a pond without any nearby lights, which could be a challenge.

By the way, see the faint smudge just off the leaves in the top right corner? That’s one of the aforementioned spiders, not quite holding still for the five-minute exposure. I actually did another shot of one above the moon (creative positioning,) using the light from the headlamp to illuminate it for a short exposure against the glare of the moon, but it didn’t come out quite the way I wanted, so that remains a project for a little later on.

At midday today the evidence of the rains still remained in places (I mean, aside from the debris knocked down by the wind and hail,) despite the temperature. Which is good – it will all vanish soon enough. In a little bit I’ll be back with more photos from today, but I’ll inform you ahead of time – all insects, and some may be considered pretty disgusting. I probably don’t have to worry about that anymore, since anyone likely to be affected by that learned their lesson long ago and hasn’t returned.

At midday today the evidence of the rains still remained in places (I mean, aside from the debris knocked down by the wind and hail,) despite the temperature. Which is good – it will all vanish soon enough. In a little bit I’ll be back with more photos from today, but I’ll inform you ahead of time – all insects, and some may be considered pretty disgusting. I probably don’t have to worry about that anymore, since anyone likely to be affected by that learned their lesson long ago and hasn’t returned.

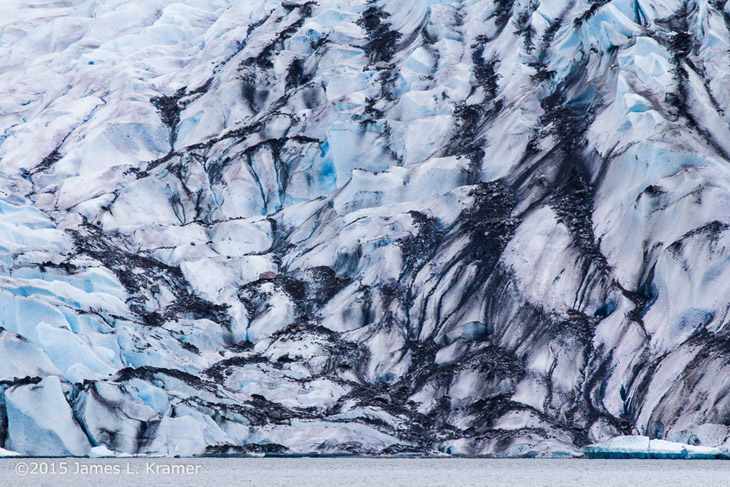

And so, we conclude our photo tour of Juneau Alaska, courtesy of Jim Kramer, unless he complains that I didn’t feature a particular image that he thought I should (you’ve seen fewer than half of what he sent me – I’m playing the editor game here.) It was a business trip with only three days of photo opportunities, so he accomplished a lot, despite the weather.

And so, we conclude our photo tour of Juneau Alaska, courtesy of Jim Kramer, unless he complains that I didn’t feature a particular image that he thought I should (you’ve seen fewer than half of what he sent me – I’m playing the editor game here.) It was a business trip with only three days of photo opportunities, so he accomplished a lot, despite the weather.

It’s safe to say that if you prefer dry air, open fields, or lots of sunlight, Alaska is not for you. But that’s minimizing the dramatic and rare vistas, and even if you don’t want to live there, it can be a fascinating visit – I admit I’m envious. It’s the kind of remote and impressive landscape that you expect nature photographers to be inhabiting, instead of, you know, college towns in North Carolina…

It’s safe to say that if you prefer dry air, open fields, or lots of sunlight, Alaska is not for you. But that’s minimizing the dramatic and rare vistas, and even if you don’t want to live there, it can be a fascinating visit – I admit I’m envious. It’s the kind of remote and impressive landscape that you expect nature photographers to be inhabiting, instead of, you know, college towns in North Carolina…

I am thinking this is looking northwest from Mount Roberts, and that splash of green is the marshy area of the northern part of the channel where the airport sits, but that’s the best I can do until Jim pipes up. I like the framing, especially with the trees reaching for the distant peak, and notice the depth provided by the layering blue haze.

I am thinking this is looking northwest from Mount Roberts, and that splash of green is the marshy area of the northern part of the channel where the airport sits, but that’s the best I can do until Jim pipes up. I like the framing, especially with the trees reaching for the distant peak, and notice the depth provided by the layering blue haze.

This is Nugget Falls, which empties into Mendenhall Lake not too far from the base of the glacier. Probably not a place to go tubing, no matter how xtreemcooldood you are.

This is Nugget Falls, which empties into Mendenhall Lake not too far from the base of the glacier. Probably not a place to go tubing, no matter how xtreemcooldood you are.

I had actually planned to have a post regarding the summer solstice pop up Sunday, nothing elaborate, but at least containing current photos, but then life happened in the form of emergency surgery. No, not for me, but for The Girlfriend’s Sprog who, in a fit of impetuous infection, callously threw away her plans to retain her appendix throughout her life. She’s fine, but we have confirmed that she doesn’t come out of anesthesia well.

I had actually planned to have a post regarding the summer solstice pop up Sunday, nothing elaborate, but at least containing current photos, but then life happened in the form of emergency surgery. No, not for me, but for The Girlfriend’s Sprog who, in a fit of impetuous infection, callously threw away her plans to retain her appendix throughout her life. She’s fine, but we have confirmed that she doesn’t come out of anesthesia well.

While retrieving her, I also spotted a frog submerging in the pond, and sat down after the turtle portraits to wait out the frog’s re-emergence. It did so only briefly, and not in a position where I could identify the species accurately, so this will remain a project for later. The pine straw seen here is ubiquitous in the yard, requiring daily removal from the pond, while the discoloration of the water is courtesy of the rains from a few days ago carrying in silt from the red clay – it will take days to settle out, and is one of the reasons why snorkeling in North Carolina is well-nigh pointless. Soon after this image was taken, The Girlfriend’s Younger Sprog said that she thought she should see a doctor, which sparked a 26-hour adventure. We’re going to ignore her next time she says that…

While retrieving her, I also spotted a frog submerging in the pond, and sat down after the turtle portraits to wait out the frog’s re-emergence. It did so only briefly, and not in a position where I could identify the species accurately, so this will remain a project for later. The pine straw seen here is ubiquitous in the yard, requiring daily removal from the pond, while the discoloration of the water is courtesy of the rains from a few days ago carrying in silt from the red clay – it will take days to settle out, and is one of the reasons why snorkeling in North Carolina is well-nigh pointless. Soon after this image was taken, The Girlfriend’s Younger Sprog said that she thought she should see a doctor, which sparked a 26-hour adventure. We’re going to ignore her next time she says that…

Since it is now ‘officially’ summer, we will perversely jump back to almost the only color to be found in wintertime, holly berries in full fruit against the brilliant green of the leaves and a rich blue sky. I will admit to being quite pleased that we can find skies like this throughout North Carolina winters; having grown up in central New York, the winters there spelled overcast conditions for the majority of the time, which could be very depressing. The few occasions when skies like this appeared, it often spelled a wicked cold front coming through and, instead of being pleasant, it was bitterly cold and windy. The decision to get the fuck out of the state came on one such day, when our water pump had failed and I was in our shack of a wellhouse trying to get it operational again in wind chill conditions down below 0°f. It’s very easy to start asking questions like, “What am I doing here?” in circumstances like that.

Since it is now ‘officially’ summer, we will perversely jump back to almost the only color to be found in wintertime, holly berries in full fruit against the brilliant green of the leaves and a rich blue sky. I will admit to being quite pleased that we can find skies like this throughout North Carolina winters; having grown up in central New York, the winters there spelled overcast conditions for the majority of the time, which could be very depressing. The few occasions when skies like this appeared, it often spelled a wicked cold front coming through and, instead of being pleasant, it was bitterly cold and windy. The decision to get the fuck out of the state came on one such day, when our water pump had failed and I was in our shack of a wellhouse trying to get it operational again in wind chill conditions down below 0°f. It’s very easy to start asking questions like, “What am I doing here?” in circumstances like that.

I used the word, “precipitous,” in the teaser, and anyone that knows me can tell you that I don’t use that word lightly. Juneau is an area of ridiculously vertical landscapes, as are quite a few portions of Alaska – not a place where Frisbees are popular, I’m betting. But you can probably hang-glide to Seattle…

I used the word, “precipitous,” in the teaser, and anyone that knows me can tell you that I don’t use that word lightly. Juneau is an area of ridiculously vertical landscapes, as are quite a few portions of Alaska – not a place where Frisbees are popular, I’m betting. But you can probably hang-glide to Seattle…

And then, the rains did come.

And then, the rains did come.

Spiders most often seek shelter, usually at one of the upper anchors of the web, but will resume position quickly, sometimes gathering drops that adhere to their bodies as they do so, though whether this is intentional to make it easy to drink, or incidental as they clamber past, is something I haven’t determined yet (and quite possibly won’t – who could tell if a spider is snagging dewdrops intentionally as it crawls across its web?) I have seen some spiders purposefully dislodging drops from the web, presumably to keep it invisible, while others seem to ignore it in the knowledge that it will evaporate quickly. Actually, there is probably no such knowledge – they just never evolved an instinct to worry about it because it never affected their survival. Let’s not credit too much cognition to the class.

Spiders most often seek shelter, usually at one of the upper anchors of the web, but will resume position quickly, sometimes gathering drops that adhere to their bodies as they do so, though whether this is intentional to make it easy to drink, or incidental as they clamber past, is something I haven’t determined yet (and quite possibly won’t – who could tell if a spider is snagging dewdrops intentionally as it crawls across its web?) I have seen some spiders purposefully dislodging drops from the web, presumably to keep it invisible, while others seem to ignore it in the knowledge that it will evaporate quickly. Actually, there is probably no such knowledge – they just never evolved an instinct to worry about it because it never affected their survival. Let’s not credit too much cognition to the class.

One little surprise appeared the other sweltering night, spotted on the downspout just after I misted the plants below, so I provided its own misting. This is likely a Copes grey treefrog (Hyla chrysoscelis) and they need the moisture, so it’s rare to see them out when it’s been so dry. Just to demonstrate my dudeness, not only did I provide a decent soaking, I turned on the deck light right overhead and left it on for a few hours in an attempt to provide more food for the little spud.

One little surprise appeared the other sweltering night, spotted on the downspout just after I misted the plants below, so I provided its own misting. This is likely a Copes grey treefrog (Hyla chrysoscelis) and they need the moisture, so it’s rare to see them out when it’s been so dry. Just to demonstrate my dudeness, not only did I provide a decent soaking, I turned on the deck light right overhead and left it on for a few hours in an attempt to provide more food for the little spud. This little stowaway couldn’t be much larger than 1mm in body length, and by flashlight it remained hard to make out, though it could be seen perambulating around on Mt Frog here. If you look closely, you can see that it has its own supply of water, a tiny droplet adhering to its leg. But in a moment, it turned to face me, and the resulting tight crop confirmed what the other images had hinted at.

This little stowaway couldn’t be much larger than 1mm in body length, and by flashlight it remained hard to make out, though it could be seen perambulating around on Mt Frog here. If you look closely, you can see that it has its own supply of water, a tiny droplet adhering to its leg. But in a moment, it turned to face me, and the resulting tight crop confirmed what the other images had hinted at.

As the storm started to settle down a bit, I could start using the timing trick; lightning seems to follow a rough pattern, with a certain amount of time between strikes occurring from the same area of cloud. Count off the seconds between strikes, then lock the shutter open about ten seconds before that time is reached again. Like I said, its rough, and it’s entirely possible that it’s merely my own confirmation bias and the strikes are more random than that – I’d need to keep some pretty specific records to be sure either way. But this image here is a successful attempt, at least. I didn’t want the amber glow from the city lights in the clouds, so the only way to accomplish that is with a short exposure that captures a flash at just the right moment, and this one was a seven-second exposure timed for the reappearance of the flash. I’m pleased.

As the storm started to settle down a bit, I could start using the timing trick; lightning seems to follow a rough pattern, with a certain amount of time between strikes occurring from the same area of cloud. Count off the seconds between strikes, then lock the shutter open about ten seconds before that time is reached again. Like I said, its rough, and it’s entirely possible that it’s merely my own confirmation bias and the strikes are more random than that – I’d need to keep some pretty specific records to be sure either way. But this image here is a successful attempt, at least. I didn’t want the amber glow from the city lights in the clouds, so the only way to accomplish that is with a short exposure that captures a flash at just the right moment, and this one was a seven-second exposure timed for the reappearance of the flash. I’m pleased.