[The location: A dark room somewhere deep in officialdom, drifting smoke obscuring the light from a single table lamp because, if you’re going to do something like this, you have to do it right.]

Shadowy Figure #1: You know something? This president is really a pain in the ass!

Shadowy Figure #2: Boy, you said it! It would be so much better with him out of the way, because he’s the sole force operating in government, and once he’s gone we’ll be able to do whatever we want.

SF1: So let’s kill him!

SF2: Why didn’t I think of that? How should we do it, though?

SF1: Well, let’s see. We have tons of resources at our disposal, the ability to create false news reports and stage elaborate scenarios, so my thinking is, we do it in a ridiculously public place with tons of witnesses, likely with cameras.

SF2: Wouldn’t it be better to make it look like an accident?

SF1: [disparaging sound] That would only arouse suspicion! No, we just need to set up someone to look like a solitary nutjob, and get rid of him quickly before he can prove he’s innocent. A bomb along a motorcade route would be perfect, easy to place ahead of time and next to untraceable.

SF2: Hmmmmm. I like the patsy idea, but a bomb sounds much too risky. How about if we do it by rifle? Witnesses would be much more likely to follow the sound of the shots and find the patsy.

SF1: Yeah, you’re right, why produce a patsy that we’re going to have to get rid of quickly and then make it too hard to find him? That would be stupid.

SF2: So let’s see, we’ll need to find a guy, and plant lots of incriminating evidence on him – a history of frustration, anger, and anti-nationalist sentiments, time spent in the Soviet Union, and maybe Cuba, employment alongside the motorcade route, bills of sale for the rifle, people who have seen him with it… how about film of him handing out pro-Cuban literature?

SF1: Dandy! Do we want to find a foreigner with no records in this country, and no family ties or anything?

SF2: No, that’s unnecessary, and probably expensive. We’ll just create some FBI files to build his entire adult history. And make sure his wife can admit to taking the photos of him posing with the gun.

SF1: One complete brainwashing – check. What else? I imagine there’s going to be cops all over the place, so we’ll need agents on hand to control their actions. What do you think, will fifty be enough?

SF2: Go with a hundred – otherwise we’d have to coach the police ahead of time to direct attention away from the wonky bits. Just make them swear not to reveal anything.

SF1: Okay, so, we send our assassin up to the top of a building during normal business hours, leaning out a window in plain sight of the crowds below. He takes his shot, then vanishes, and the cops arrest the patsy. Make sure patsy’s fingerprints can be found on the gun, but our guy manages not to obliterate them, got it?

SF1: No problem. Now, this lone gunman thing, it seems a little risky. Should we have backup?

SF2: Yeeeaahhhh, let’s put another gunman at ground level, at the very edge of the crowd, right where his shot can be easily spoiled.

SF1: I don’t like it. What if he’s spotted? What about the additional rifle sounds? And how will he get away?

SF2: We put him behind a fence, see? No one will know a thing. And there won’t be enough witnesses to pinpoint whether the rifle sounds came from the top of the building or right behind their fucking heads. Then he’ll just scamper off through the throngs of police converging on the scene. If anyone stops him he’ll just flash a badge – cops won’t bother questioning him then.

SF1: [Nodding] I can see how that would work. Let’s get cracking!

[On the fateful day]

SF1: Bad news, 2! The patsy walked past the cops and wasn’t arrested!

SF2: Can’t have that – we’d have wasted all this effort. Let’s see, let’s see… [long pause] Okay, shoot a cop, about a mile from the patsy’s house – make sure there are witnesses, so get a guy that looks exactly like our patsy, same jacket he just put on ten minutes ago and everything. Then find the patsy and plant the gun on him, so he has it when he’s arrested – even though he’s perfectly innocent, he’ll brandish the damn thing in front of dozens of witnesses and try to fight with the cops.

SF1: I like it! But he can still talk, so we still have to get rid of him, or the entire thing’s blown. Is our other agent in place?

SF2: Yep! He’ll go wandering all over town running errands to create his alibi, then step up right as the patsy is being transferred and pop him one in the gut, in front of dozens of police officers who could ruin the whole damn thing. It’s perfect!

[A day later]

SF2: This isn’t good. Somebody got movie film of our second gunman finishing the job, right from an ideal vantage point. Should we have it confiscated as evidence?

SF1: No, you idiot! That’s just what they’d expect us to do! Just make a couple of copies of it and let him sell it to a major news company.

SF2: But… it shows our target’s head snapping back, and to the left – back, and to the left. Won’t that arouse suspicion?

SF1: What do you want us to do, bury it? It’s the one thing that every armchair sleuth would seize onto as evidence the shot came from the front! Of course it has to go public!

SF2: Okay, now you’re not making sense.

SF1: [Rolls eyes behind sunglasses] If everything goes so smoothly that no one suspects a thing, that will be suspicious in itself, see? So we do something so incredibly stupid, something that could ruin hundreds of little details that we’ve worked so hard on, that it’ll throw everyone off – logically, we’d never let something as incriminating as that go past, so there must not be a conspiracy.

SF2: That’s… that’s just brilliant!

SF1: You have to understand how people’s minds work. No one would believe we’d miss the most obvious problem in the world.

[Some weeks later]

SF1: So, how’s it going?

SF2: Excellent! While witnesses claim at least three shots, sometimes four, our guys on the report are going with one bullet unaccounted for, and the kill shot lost as well, leaving just one that went through the target, through the seat, and gave multiple wounds to the governor. Ballistics experts and doctors who specialize in gunshot wounds are all vouching that the kill shot came from the rear, and the pesky exit wound from our guy on the rise was eliminated with CGI. We’ve hidden the extra bullet holes in the seat – lucky for us no one heard all the extra shots – and not one witness standing right in front of our backup assassin heard the discharges behind them.

SF1: Now, see? Isn’t this so much better than a bomb or a plane crash? Much less planning, that’s for sure.

SF2: You said it!

* * * * *

While I admit to feeling a little annoyed with myself for jumping on the bandwagon, at least this isn’t a post having anything to do with Meleagris gallopavo. And far be it from me to let an opportunity for elaborate sarcasm slide…

Yet, the point is perfectly serious, and something that is very frequently missed by those who seem intent on examining every tiny detail. Almost no one sits back and examines their conspiracy scenario from the standpoint of plausibility, and how likely it is that anyone would actually plan something in this manner, especially something as elaborate as the Kennedy assassination or World Trade Center collapse. If someone really wanted to stage any such event and make it look like something else, there are millions of easier ways to do it. Why involve several dozen to hundreds of confederates when you could use a small handful looking the other way while the car was doctored?

There’s a curious trait at work herein, too. All it takes is just one factor that seems off – in this case, Kennedy’s head snapping in a seemingly unnatural direction (you have to hand it to the Zapruder film, which in 26 seconds created thousands of ballistics and forensics experts.) Once someone seizes on this as suspicious, they then start to look for other suspicious factors as well – and the bare truth is, if we want to see them, they can be found anywhere. And every one becomes fodder for the contrivance [none of them deserve the word ‘theory’], fed by our innate delight in puzzles. My favorite Suspicious Detail is the “Umbrella Man,” some guy who opened his umbrella as the motorcade went past, in protest of Kennedy’s appeasement practices with the Soviet Union – it’s a Neville Chamberlain reference. Of course, this was promoted as a signal to the assassin(s), as if they would need a signal of, what? The car reaching a certain spot? Kennedy being in a clear line of fire? Is there something that somehow wouldn’t be plainly visible to the guy behind the rifle? It serves no purpose, but it’s curious, so it means something.

(Even better, Umbrella Man has also been accused of firing a poison dart, because of course this makes perfect sense.)

Most times, no suspicious factor ties in with any other in a coherent way, instead requiring another explanation, another piece of speculation, to support it. That’s not solving a puzzle, however – it’s building an edifice, finding ways to shore up a foregone conclusion instead of seeing what direction the evidence, all of the evidence, leads. And the edifice that results is usually a rickety, swaying thing that stands on faith alone, because there’s nothing solid beneath it.

Undoubtedly, a lot of the more fervent conspiracy mongers could tear apart my conversation above, claiming I didn’t disprove their cherished little plot (there’s only a million of them, and curiously, none of them in agreement,) but of course that misses the point. The point is, is any explanation logically sound, and by extension more sound than Oswald acting alone? If any of the hundreds of parties who had Sufficient Motive had actually plotted to assassinate the President, what would make them settle on such a Rube Goldberg design involving thousands of details and elaborate planning?

And then, there’s one little question I have for all those who insist that there’s a conspiracy, anywhere: What are you suggesting we do about it? Let’s assume the moon landings were all faked. Fine – what now? Bin Laden wasn’t killed when we were told he was. Okay – so? I mean, you do have a plan of action that you worked out in all the time spent on this, and aren’t simply trying to find some way to feel superior… right?

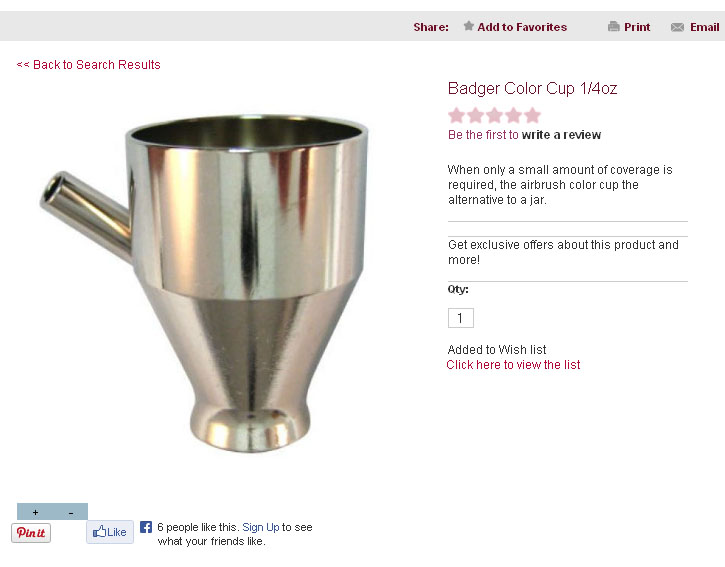

The followup: I found one on eBay, would have been just over five bucks with shipping if I didn’t get into a stupid bidding war. The item is worth about two bucks, and six is the maximum I would pay for the damn thing (which, as I would come to find out, is less than half what Michaels wanted for it.) So while waiting for the bid close date to come along, I just made my own, from a brass pipe I had and a plastic cap. Works perfectly.

The followup: I found one on eBay, would have been just over five bucks with shipping if I didn’t get into a stupid bidding war. The item is worth about two bucks, and six is the maximum I would pay for the damn thing (which, as I would come to find out, is less than half what Michaels wanted for it.) So while waiting for the bid close date to come along, I just made my own, from a brass pipe I had and a plastic cap. Works perfectly. Now, let me introduce a few points. I am, among other things, a spider photographer, which means not only do I have close contact with them very frequently, I also seek them out, and look closely at any I might stumble across, and that’s nearly daily. There is not any experience of mine that I can point to as definitely a spider bite, though I am chewed up routinely by mosquitoes and other various parasites, not to mention encounters with bees,

Now, let me introduce a few points. I am, among other things, a spider photographer, which means not only do I have close contact with them very frequently, I also seek them out, and look closely at any I might stumble across, and that’s nearly daily. There is not any experience of mine that I can point to as definitely a spider bite, though I am chewed up routinely by mosquitoes and other various parasites, not to mention encounters with bees,

Anyway, I still think the frost image above could be better, and if I get out tomorrow morning early enough we’ll see if I can improve on it. I feel the same way about the picture at left, even though this was a re-shoot; I’d taken one the same time as the frost pic (well, not exactly the same time, a talent I haven’t yet mastered, but a few minutes later,) but the flower was in full sunlight and that was making the contrast too high to get the best results from. The petals were blown out to pure white in ‘normal’ exposures, and the rest became too dark when that was controlled for, so I did it again while using the softboxed flash. I’m pleased with the leaves in foreground and background – the flower really was poking up through the leaf litter – but the petals seem off. They’re not only a little too symmetrical, they’re closely matched with the green leaves behind, seeming more, I dunno, geometric than we’d expect. Maybe it’s just me. I do like the prominence of the curled petal, which is why I chose this position and angle.

Anyway, I still think the frost image above could be better, and if I get out tomorrow morning early enough we’ll see if I can improve on it. I feel the same way about the picture at left, even though this was a re-shoot; I’d taken one the same time as the frost pic (well, not exactly the same time, a talent I haven’t yet mastered, but a few minutes later,) but the flower was in full sunlight and that was making the contrast too high to get the best results from. The petals were blown out to pure white in ‘normal’ exposures, and the rest became too dark when that was controlled for, so I did it again while using the softboxed flash. I’m pleased with the leaves in foreground and background – the flower really was poking up through the leaf litter – but the petals seem off. They’re not only a little too symmetrical, they’re closely matched with the green leaves behind, seeming more, I dunno, geometric than we’d expect. Maybe it’s just me. I do like the prominence of the curled petal, which is why I chose this position and angle. This is what’s so hard about teaching composition, because countless different factors come into play for any image, and that’s just considering one style of shooting, of which everyone has their own. It’s easy to overwhelm new photographers with loads of compositional elements, and no way to define which should be used for any particular image or approach. Here, some dried pokeberries (genus Phytolacca) had produced an interesting effect with the shiny black seeds poking through the decrepit remains of the berries – somehow, the mockingbirds did not discover them this year. But, just using the posts on composition that I’ve made so far, how many different elements were actually used here?

This is what’s so hard about teaching composition, because countless different factors come into play for any image, and that’s just considering one style of shooting, of which everyone has their own. It’s easy to overwhelm new photographers with loads of compositional elements, and no way to define which should be used for any particular image or approach. Here, some dried pokeberries (genus Phytolacca) had produced an interesting effect with the shiny black seeds poking through the decrepit remains of the berries – somehow, the mockingbirds did not discover them this year. But, just using the posts on composition that I’ve made so far, how many different elements were actually used here? It’s not just one image, either – I shot the same subject under a diffusing cloth to simulate light shade, in hazy conditions on another day (seen here,) and at night in completely controlled lighting. I used other portions of the plant or the lawn as backgrounds and even hung a few leaves from a wire close behind for the night shot (because the flash wasn’t going to

It’s not just one image, either – I shot the same subject under a diffusing cloth to simulate light shade, in hazy conditions on another day (seen here,) and at night in completely controlled lighting. I used other portions of the plant or the lawn as backgrounds and even hung a few leaves from a wire close behind for the night shot (because the flash wasn’t going to  In recognition (or defense) of the previous post, I’m much more used to expressing myself in this manner, letting nature take most of the credit. Anyone is free to ascribe their own words, feelings, or impressions to the images. Granted, it’s strictly visual, which might be considered lacking if someone didn’t have their own experiences with autumn, but in all other cases, our associative minds can take the visual input and conjure up the sounds, smells, and even temperatures that are cataloged right alongside.

In recognition (or defense) of the previous post, I’m much more used to expressing myself in this manner, letting nature take most of the credit. Anyone is free to ascribe their own words, feelings, or impressions to the images. Granted, it’s strictly visual, which might be considered lacking if someone didn’t have their own experiences with autumn, but in all other cases, our associative minds can take the visual input and conjure up the sounds, smells, and even temperatures that are cataloged right alongside.

Yet, nature has a pretty good grasp on things, and the mother who deposited these eggs was following a behavioral plan dictated by thousands of years of selection – unless, of course, something went wrong. Of 138 eggs (yes I counted them, but in the image where I could Photoshop a colored dot to hold my place,) four are visibly non-viable, and who knows how many more genetic defects might be present, or were present in the previous generation? It remains possible that the mother who laid these was a bit funny in the head. However, I’m betting that this is business as usual and these little wrigglies are well-equipped to deal with the conditions. The newborn is visible in this pic too, just right of center, so as you can imagine from that, following their progress once they leave the distinctive surrounds of the egg cluster would be next to impossible. While I might find larger caterpillars later on, there would be little chance of determining if they were these hatchlings or not, and even keeping a few in a terrarium would require finding the right food for them, which would be only a wild guess on my part. I’ll assume nature’s got a handle on it.

Yet, nature has a pretty good grasp on things, and the mother who deposited these eggs was following a behavioral plan dictated by thousands of years of selection – unless, of course, something went wrong. Of 138 eggs (yes I counted them, but in the image where I could Photoshop a colored dot to hold my place,) four are visibly non-viable, and who knows how many more genetic defects might be present, or were present in the previous generation? It remains possible that the mother who laid these was a bit funny in the head. However, I’m betting that this is business as usual and these little wrigglies are well-equipped to deal with the conditions. The newborn is visible in this pic too, just right of center, so as you can imagine from that, following their progress once they leave the distinctive surrounds of the egg cluster would be next to impossible. While I might find larger caterpillars later on, there would be little chance of determining if they were these hatchlings or not, and even keeping a few in a terrarium would require finding the right food for them, which would be only a wild guess on my part. I’ll assume nature’s got a handle on it.