Widely mixed, even.

So Buggato and I had another outing yesterday, once again to Jordan Lake because, while plants are indeed budding out around here, full bloom is a ways off; meanwhile, we’re keeping an eye on bird activity at the lake. And in some cases, it was active.

While seeing double-crested cormorants (Nannopterum auritum) is fairly easy down there, yesterday they were out in force, and flocking right overhead in numerous cases – we saw hundreds. I wasn’t too fired up about snagging photos because I have more than a few of the species, in flight and perched and quite close, but I collected a few frames anyway, including several as they flew past in what almost amounted to a cloud – I had the long lens attached so no wide angle shots for this one. If I really wanted to be ‘prepared,’ I’d have a second body with the 18-135 attached along as well, but I’m already carrying too much weight and this would also necessitate using neck straps, which I passionately abhor. If you really want the impression, multiply this image here by a couple dozen and composite them together in a giant frame.

We were, naturally, keeping a close eye out for eagles, which did indeed make appearances, but almost always at a significant distance – the closest was directly over the road as we approached our parking spot in the car, perhaps a hundred meters away (which is plenty close enough,) but being in a car in the middle of the road we could do nothing about it, and that one failed to reappear later on. They know.

However, while watching one at least three times as distant wheeling around, I managed to snag a pretty nice shot anyway.

This is at full resolution from the 600mm lens, so very distant indeed, but the pose and lighting were perfect, and show the captured fish distinctly. This was curious to me, however, because the eagle had been wheeling out there for several passes and I’d never seen the capture, so it was carrying a fish around in circles for a while. Normally, they immediately head to a safe place to eat it, usually well out of sight, or deposit it at the nest for the young-uns, but it’s still a little too early for hatchling season around here. Showing off its hunting prowess for a potential mate? Perhaps, though no other eagle was visible at all, so there’s no additional support for that conjecture. Maybe it simply didn’t like wet food…

The day, by the way, was quite warm but ridiculously windy, enough so that we remained very wary while among the various dead trees in the area – it was the kind of conditions to bring them down, and while that might be a fitting demise for a nature photographer, I personally am aiming for being savaged by an angry wombat when I’m 100 or so; the close-up photos of a gaping gullet would bring me posthumous fame at least. Overall, however, the birds weren’t performing well enough to make it a decent session, but we were also out there for both the sunset and the moonrise, so we waited out the fading light.

Sunset, as predicted, was boring – a completely cloudless sky and only moderate humidity meant a yellow sun and very sparse sky color, but right after it went down I did a few frames on the lake just for the sake of having something.

A few kayakers and a sailboat coincided within view against the spot where the sun had disappeared, the best I was finding, so I tripped a few frames, capturing a huge backlit swarm of insects, likely midges, while doing so – that’s all the speckling against the trees, and of course they’re several times closer than the kayakers were. The wind was greatly reduced by this point yet not totally subsided, and I would have thought that would reduce the swarming behavior too, but oh well.

On the opposite horizon, the haze was looking a little thick, and I wondered about the conditions for the rising moon, but I put some of this down to shadows at sunset. It seemed a tad late in coming, but eventually the moon peeked over the trees, the brilliant color of a glowing ember and not obscured at all.

The humidity provided lots of distortion, however, including a separated greenish cap, but at no point did even a thin band of clouds give the moon something to pass behind. The clarity of the lunar mares was significant, and we fired off countless frames as the moon rose, brightened, and changed color.

The traffic into the nearby airport (Raleigh-Durham/RDU) was almost nonstop all afternoon, and the lake lay within the approach paths, so I was holding out hope that we might pull something off, something that I’ve been after for better than 25 years. Yet as the moon rose, the traffic virtually stopped, and I was worried that the opportunity wouldn’t present itself. Patience paid off however, and I accomplished this goal not just once, but twice.

Not just silhouetted against the moon, but with distinct clarity, showing the distortion from the jetwash along the right edge as well. And with the gear down for landing. Finally!

[In my defense, I haven’t been obsessive about this endeavor, going out every clear night with a full moon and watching for air traffic, but it’s been a goal every time I have been out photographing the moon, ever since my first attempts back sometime in ’96 or ’97. As easy as it seems like it might be, provided you’re close enough to decent air traffic, the path to cross the moon is actually very narrow, and the moon is constantly moving itself – we watched two other plans pass above and below the moon while out there. I’ll also point out that, due to not paying close enough attention, I just barely missed my opportunity last year right before the (first) total lunar eclipse.]

A little later on, the moon was still brightening and changing color, though at this point it was surprisingly a little greenish.

Whether this was due to the humidity, airborne particulates, or the camera settings, I can’t say – I was doing several frames with the low, middle, and high contrast/saturation settings for comparison, but I don’t see why these should have imparted a color cast, and I was using sunlight white-balance as usual, which should have captured it as-is. But for additional comparison, I include a full-resolution crop of the same image.

Some of those edge effects are atmospheric distortion, some of those are the moon being not perfectly full and thus that side dropping into shadow. But mostly what this is here for is to compare against the eagle shot above, because they were both shot at the same magnification/focal length, so you can look at the moon against the sky some night and realize that the eagle was perhaps half that in wingpspread. And no, I’m not likely to get an eagle against the moon anytime soon, because they don’t fly at night, but maybe someday I’ll pin one against a gibbous moon in early morning or late afternoon; if the same pattern holds, I’ll be in my eighties then, yet still some years away from the wombat incident.

I’ll close with another frame in the opposite direction again, back towards the deepening twilight well after sunset.

That speck towards upper left is Venus, and almost straight below it, a lot more subtle, is Jupiter – no stars were yet showing. Seven days ago Venus and Jupiter were just a finger-width apart, but of course we were seeing heavy rains here at that time. This was about the best color that the sky produced last night, so sunset was a bust, but we had enough successes overall for the session.

This main image might seem confusing when you see the lighthouse from the outside, because it looks almost globular here, yet exterior shots show straight, cylindrical sides. While there is a little wide-angle distortion in my image (shot at 21mm focal length,) it’s not that distinct – but the lens assembly is separate from the exterior housing and in indeed closer to globular – more like a squat pear shape, really, but the top is pretty small. If you look, you can see the white frames of the exterior housing through the lenses here. Even more interesting, the roof of the structure should extend out at least to the outer ring of the lens assembly and darken it, shadowing most of the frame, but the fresnel lens distortion prevent it from being seen at all.

This main image might seem confusing when you see the lighthouse from the outside, because it looks almost globular here, yet exterior shots show straight, cylindrical sides. While there is a little wide-angle distortion in my image (shot at 21mm focal length,) it’s not that distinct – but the lens assembly is separate from the exterior housing and in indeed closer to globular – more like a squat pear shape, really, but the top is pretty small. If you look, you can see the white frames of the exterior housing through the lenses here. Even more interesting, the roof of the structure should extend out at least to the outer ring of the lens assembly and darken it, shadowing most of the frame, but the fresnel lens distortion prevent it from being seen at all.

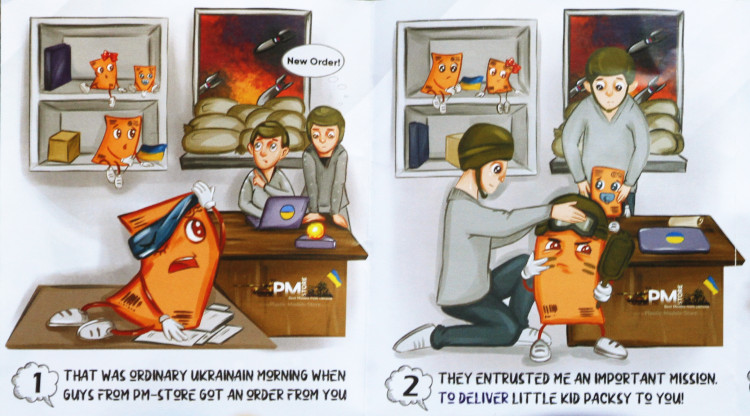

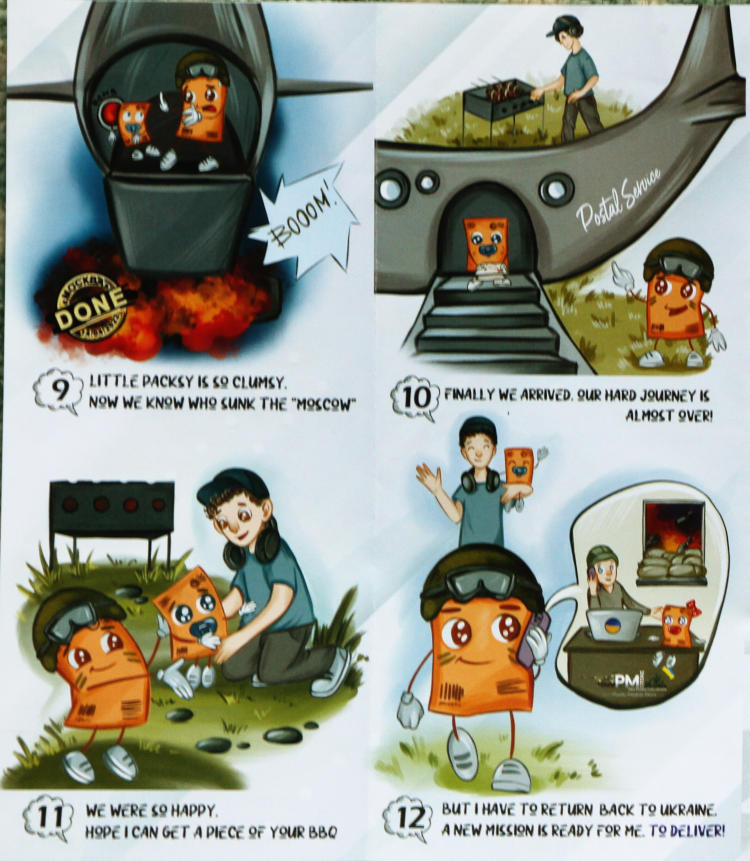

One year ago today, Russia invaded Ukraine in a phenomenally stupid attempt to re-absorb the territory as their own, so this seemed the best time to post this (given as how I forgot about this little featured aspect until just recently.) Like most of the country, I stand 100% behind Ukraine in this regard. Until the invasion, I knew Putin was a return to the totalitarian mindset maintained throughout the Soviet Union years, but the invasion certified him as a megalomaniac, and not a very bright one – no wonder Florida Man is on good terms with him (that would be Trump, but this is the last time you’ll see that name here, because Florida Man fits him oh so much better.)

One year ago today, Russia invaded Ukraine in a phenomenally stupid attempt to re-absorb the territory as their own, so this seemed the best time to post this (given as how I forgot about this little featured aspect until just recently.) Like most of the country, I stand 100% behind Ukraine in this regard. Until the invasion, I knew Putin was a return to the totalitarian mindset maintained throughout the Soviet Union years, but the invasion certified him as a megalomaniac, and not a very bright one – no wonder Florida Man is on good terms with him (that would be Trump, but this is the last time you’ll see that name here, because Florida Man fits him oh so much better.)