Sure, spring means flowers and new foliage and all that, but it also means a lot of other things too, ones never covered by any media outlet that exists. Here’s a look at the creepier signs of spring.

As The Girlfriend and I were coming in the back door yesterday, I spotted a flash of movement on the deck railing, which turned out to be a newly-hatched praying mantis. Now, I have a mantis egg case in a terrarium on the back porch, having found it on a photo outing a couple of weeks ago where the supporting plant had been mown down, and I’ve been waiting to see if it will hatch – my subject here is not evidence of that, however. I scooped it up and transferred it to the Japanese maple out front, which had hosted a collection of mantids when we moved in last year, in the hopes that I might maintain another resident that I could observe routinely (and that perhaps this one would avoid marauding deer.)

That’s the cutest image of this post; it’s all downhill from here, folks.

Spring is naturally the birthing season of many species, and while checking out a new locale for outings, I spied a tree stump topped with what appeared to be white nylon netting – you get the benefit of the closer examination and can see it’s a nursery for newborn spiders, most likely a variety of purseweb spiders (genus Sphodros) – those huge chelicerae are rather distinctive, even at this age. I hadn’t brought the full macro kit and just shot a bunch of frames to try and snag enough details, without going for illustrations or art this time. I admit to never having seen this species before at all – I’m quite sure I would have remembered it.

The arthropods aren’t the only things breeding right now, of course, and in a park a few days beforehand, I snagged a chorus frog, probably a spring peeper (Hyla crucifer) though its markings are obscured enough by the mud to prevent confidence, sitting amongst a random scattering of tadpoles and duckweed. I doubt the tadpoles are the same species as the frog, but I don’t think there’s actually any way to tell for sure without laboratory examination.

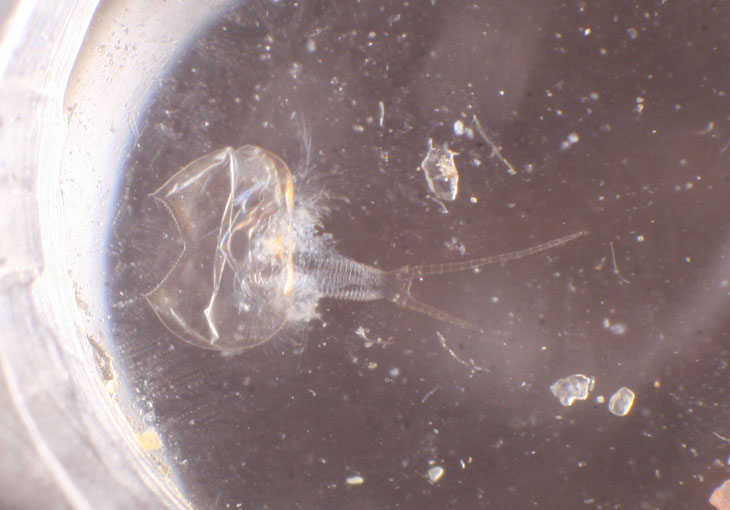

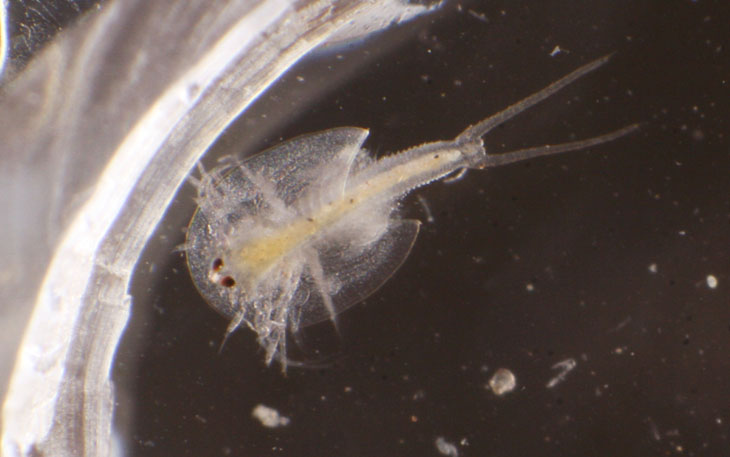

Not everything is on the same schedule. On the same trip as the previous post, actually while standing on the same rock seen in the middle of the opening shot, I watched what I thought were some very large water striders (family Gerridae,) only to find when editing the images that they only appeared that large because they had two backs, as they say (a different ‘they’ this time – the striders were silent on the subject.) Judging from both memory and the photos I got at the time, I never saw any single striders, so perhaps New Hope Creek has qualities other than being ideal for water snakes.

Believe it or not, these jumping spiders (genus Phidippus) found last night might have recently been engaged in the same behavior, more or less. Near as I can tell, they’re the same species, and spiders often have a hazardous love life (read the follow-up post too when you go to that link.) The one on the right might be a female that seized her potential mate either before or after the deed; ‘getting lucky’ has an entirely different meaning in spider culture.

I photographed four different spider species last night, and at least two had meals – a third appears like it might also have had one, but I was unable to get a clear enough shot to be sure. Note that I was unable to determine it for any of them at the time, only discovering it once I’d seen the photos, though with this wolf spider (family Lycosidae) I suspected it, since I could make out some motion in under the face – I’m guessing, since I see them all over the place, that its meal is an inchworm; you can see the splash of bright green alongside the victim’s head. The captured images are often different from what I see through the viewfinder, especially for small subjects. For macro work, I usually have to shoot with the assistance of a small gooseneck flashlight attached to the softboxed strobe; it’s significantly dimmer than the strobe and often coming in at a different light angle, so it’s not until I unload the memory card that I know for sure how much detail I’ve captured (and for the very high magnification shots, whether I even achieved critical focus.)

I photographed four different spider species last night, and at least two had meals – a third appears like it might also have had one, but I was unable to get a clear enough shot to be sure. Note that I was unable to determine it for any of them at the time, only discovering it once I’d seen the photos, though with this wolf spider (family Lycosidae) I suspected it, since I could make out some motion in under the face – I’m guessing, since I see them all over the place, that its meal is an inchworm; you can see the splash of bright green alongside the victim’s head. The captured images are often different from what I see through the viewfinder, especially for small subjects. For macro work, I usually have to shoot with the assistance of a small gooseneck flashlight attached to the softboxed strobe; it’s significantly dimmer than the strobe and often coming in at a different light angle, so it’s not until I unload the memory card that I know for sure how much detail I’ve captured (and for the very high magnification shots, whether I even achieved critical focus.)

I admit that I’m very fond of going in for the portrait shots with spiders, since most times what we see are just the straight-down, leg spread images. These are more ominous of course, placing the viewer right in the implied attention of the arachnid, but also a bit misleading; my model here would only span across a large coin, big enough to be creepy but hardly an imposing specimen.

The effect is even more pronounced here. The new salvia blooms can’t give the best indication, since they come in a huge variety of flower sizes, but suffice to say my plant here is perhaps the smallest variety – those specks on the flower are pollen grains, and the spider itself could fit comfortably on your fingernail without overlap. In body length and mass, it was less than half the size of the jumping spiders above, themselves only average for the family. I interrupted this one as she was spinning a web between the flower stalks, obviously counting on the coming attraction of the opening flowers.

But this is the other side of the coin. Found on Morgan Creek, again, on the same outing as the previous post, this fishing spider (probably Dolomedes tenebrosus) was quite a bit larger than the wolf spider, perhaps spanning 6 cm across the legs. I would have done a face shot for this one too, but she was far too shy and darted under cover as I moved into position. I’ve been watching for the fishing spiders for the past couple of weeks, having seen only a small one on a tree trunk until now, but this trip netted me at least five.

But this is the other side of the coin. Found on Morgan Creek, again, on the same outing as the previous post, this fishing spider (probably Dolomedes tenebrosus) was quite a bit larger than the wolf spider, perhaps spanning 6 cm across the legs. I would have done a face shot for this one too, but she was far too shy and darted under cover as I moved into position. I’ve been watching for the fishing spiders for the past couple of weeks, having seen only a small one on a tree trunk until now, but this trip netted me at least five.

And, for mercy, I’ll close with a fartsy one from yesterday. It’s been gloomy all day today and is raining as I type this, and this shows the weather closing in yesterday, but if you look at the top and bottom of the pic, there’s still blue sky showing in the reflection. I just wanted those complicated clouds against the stark branches, and the placid water produced the clarity necessary.

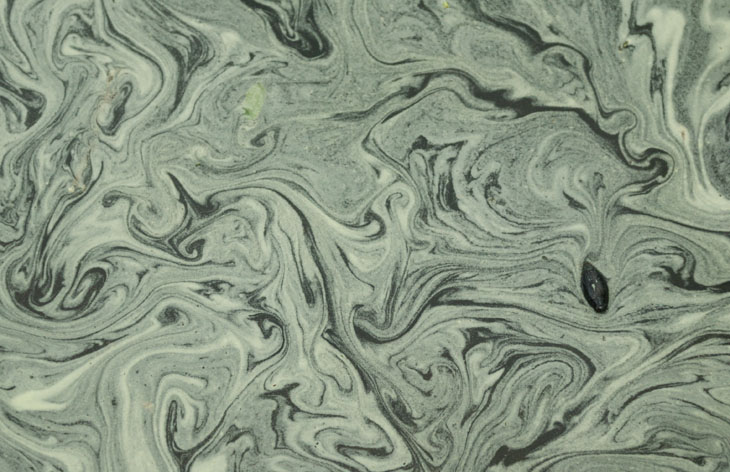

If you’re looking for water snakes in central NC, this is the place to go – I’m not sure I’ve ever been here during their active months and not seen a snake. These are both northern water snakes (Nerodia sipedon,) which tend to be large, impressive snakes, almost always less than a meter in length but sometimes as thick as my wrist. Both were seen from the concrete apron that crosses the creekbed, which yesterday was showing the effects of the recent rains in that the creek was spilling over the top up to 15 cm deep. These two images give a faint impression of how hard it is to illustrate snake markings; even though they’re the same species, you can see the difference in coloration, and the brightness can vary even more than this, partially due to genetics, but also due to how long it has been since the last time the individual has shed its skin – they’re darkest when due, and brightest immediately afterward. It also varies depending on how long they’re been out of the water, appearing brightest when wet. Not far from here, we also saw a queen snake (Regina septemvittata, what a great name,) which is considerably less impressive in appearance though similar in behavior.

If you’re looking for water snakes in central NC, this is the place to go – I’m not sure I’ve ever been here during their active months and not seen a snake. These are both northern water snakes (Nerodia sipedon,) which tend to be large, impressive snakes, almost always less than a meter in length but sometimes as thick as my wrist. Both were seen from the concrete apron that crosses the creekbed, which yesterday was showing the effects of the recent rains in that the creek was spilling over the top up to 15 cm deep. These two images give a faint impression of how hard it is to illustrate snake markings; even though they’re the same species, you can see the difference in coloration, and the brightness can vary even more than this, partially due to genetics, but also due to how long it has been since the last time the individual has shed its skin – they’re darkest when due, and brightest immediately afterward. It also varies depending on how long they’re been out of the water, appearing brightest when wet. Not far from here, we also saw a queen snake (Regina septemvittata, what a great name,) which is considerably less impressive in appearance though similar in behavior.

We hadn’t really exhausted all of the possibilities of Duke Forest, but I had an errand to run, so after that we went back to Mason Farm Preserve for a short while, where I stuck to fartsy images, like getting into Morgan Creek and taking this frame down just above water level. I’m shooting with a Canon 30D, which doesn’t have a fancy swing-out LCD or real-time display (old-fashioned optical viewfinder – I know, right?) so this one was shot blind. Except for a slight tweak back to level, this is the perspective I was after.

We hadn’t really exhausted all of the possibilities of Duke Forest, but I had an errand to run, so after that we went back to Mason Farm Preserve for a short while, where I stuck to fartsy images, like getting into Morgan Creek and taking this frame down just above water level. I’m shooting with a Canon 30D, which doesn’t have a fancy swing-out LCD or real-time display (old-fashioned optical viewfinder – I know, right?) so this one was shot blind. Except for a slight tweak back to level, this is the perspective I was after.

I guess I’m not shocking anyone when I say this is not how I intended this image to look at all. And it’s a shame, because it was a rare opportunity that might actually have come out with some artistic merit.

I guess I’m not shocking anyone when I say this is not how I intended this image to look at all. And it’s a shame, because it was a rare opportunity that might actually have come out with some artistic merit.

Or, kinda chartreuse.

Or, kinda chartreuse.

I’ve said it before, numerous times, but lightning photography can be challenging. Where and when the bolts will appear is, of course, wildly variable, and getting a good setting, preferably with some foreground interest, lined up with the active part of a storm is also tricky. And then there’s the rain, which naturally you won’t want your equipment in even if you’re cool with it yourself. It was raining hard enough that I not only was shooting out of the open side door of the van, but I had to back up a bit to keep the wind from blowing rain onto the camera. In the image above, you can see the edges of the van intruding into the photo, but one other thing which I would have liked to have occurred more often: a bright strike had occurred behind me, illuminating the foreground trees just enough to give them a little color and distinction beyond ‘silhouette.’ Too bad that’s the only thing that image has going for it. Both of these have barely visible bolts within them, but well off to the side, small and undramatic. That happens a lot too, but I have even more frames with just cloud glow, no visible lightning at all.

I’ve said it before, numerous times, but lightning photography can be challenging. Where and when the bolts will appear is, of course, wildly variable, and getting a good setting, preferably with some foreground interest, lined up with the active part of a storm is also tricky. And then there’s the rain, which naturally you won’t want your equipment in even if you’re cool with it yourself. It was raining hard enough that I not only was shooting out of the open side door of the van, but I had to back up a bit to keep the wind from blowing rain onto the camera. In the image above, you can see the edges of the van intruding into the photo, but one other thing which I would have liked to have occurred more often: a bright strike had occurred behind me, illuminating the foreground trees just enough to give them a little color and distinction beyond ‘silhouette.’ Too bad that’s the only thing that image has going for it. Both of these have barely visible bolts within them, but well off to the side, small and undramatic. That happens a lot too, but I have even more frames with just cloud glow, no visible lightning at all.

I felt like I just had to do this, for some reason…

I felt like I just had to do this, for some reason…