Last night the lightning alert was going off madly, and the maps showed a couple of massive cells passing through, but not quite getting to us – they looked to be missing us by a small margin off to the west. Encouraged by this, I headed down to the waterfront because that afforded the best views east and west (actually, more west-northwest and east-southeast, but you take what you can get.) And it was quite active; I did a few video clips because that was the only way to demonstrate this.

A short note: the exposure meter wanted to render it brighter than it actually was, and I hadn’t tried dialing in any compensation, so this made it distinctly grainy. That’s okay – we’re not after accuracy in brightness, just seeing how often the lightning was firing off.

I didn’t bother with a voiceover because I wanted you to hear the sounds, which were – nothing, really; the loudest thing in there isn’t thunder at all, was just the breeze beating against the microphone since I hadn’t used the external mic that has a wind guard. The whole time I was out there, only the barest rumble of thunder carried through – this was mostly high-altitude, cloud-to-cloud stuff. And while the clip is only thirty seconds, this light show continued for perhaps twenty minutes, as the cells slowly moved northward without seeming to come closer. Of course, I did some still photography as well, a few time exposures to see if I could capture any visible bolts.

This is just to set the scene. I was running roughly 10-15 second exposures because the waterfront lighting was illuminating the foreground elements quite a bit, so I purposefully darkened this frame down to represent what it actually looked like, more or less – there were only a couple of instances where such short exposures still didn’t yield any noticeable sky lights. It was just before 9:00 PM locally – the sun had set not half an hour before, and without the clouds it would have still been twilight. But now the comparison:

These were back to back frames, though this one had actually come first, 11 seconds as opposed to 9, but not darkened to match visible conditions – look at the pilings in the foreground. Since this is at 18mm focal length, you know it’s showing multiple cell strikes in there. And in fact, I did, barely, catch a visible bolt, down there on the horizon peeking out from the cloud deck. A closer look:

Not the kind of thing that I’m trying to capture (well, it is, only much bigger and much closer,) but at least I caught something.

And again,

Yep, there’s another down there, looking like this:

This spot seemed to produce the brighter and more noticeable sky bursts, even when I never saw these bolts as they occurred, so I set up in a slightly different position to try and take advantage of this. While there was no activity:

Again, darkened to appear more accurate. The new position was actually successful, which is usually more miss than hit when it comes to electrical storms (probably not the best phrasing):

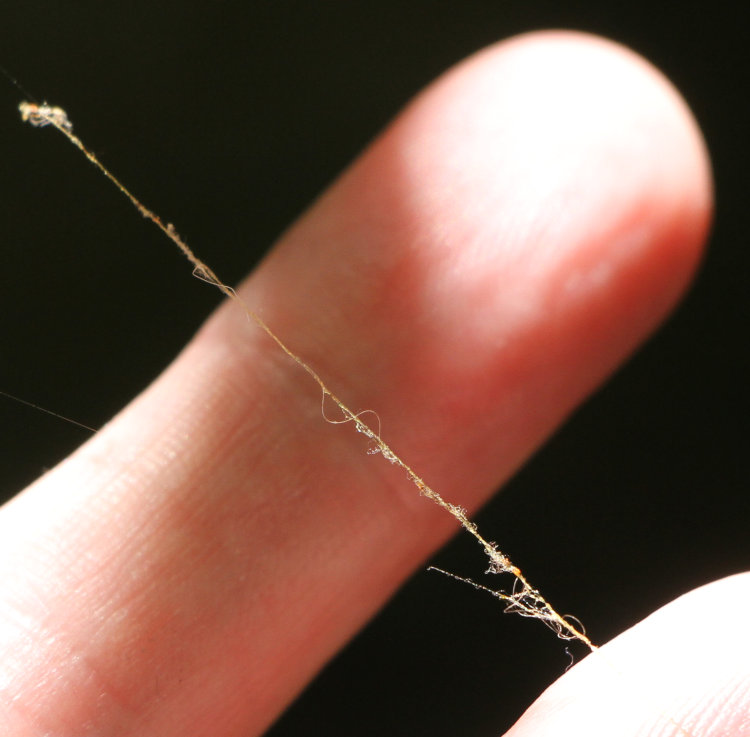

Well, technically successful, but as noted before, not what I was really after, and it intertwined with the mast of a foreground sailboat:

This is, as close as can possibly be determined, in the same location as the previous bolt capture – I was the one that had shifted position, as comparing the location of that sailboat mast will show.

My favorite image for the night, however, was this one:

This was easily the most active cell, though it was also a hair too far north to see underneath with the buildings there. While I was out, this cell gradually moved well behind the trees and the other was petering out, so I wrapped things up for the evening, having heard only the faintest rumble of thunder the entire time. The breeze off of the water felt great after the hot days we’ve been having, though, so it was a nice night.

A few hours later, another collection of cells (I honestly have no idea how many,) did actually pass through our area, producing at least three separate horrendous downpours, perhaps more, and a few lightning strikes that were within half a kilometer as we were trying to sleep. It’s been that kind of weather recently, and I’m used to hearing the lightning alert on my smutphone just about every hour, though the sources of most alerts aren’t actually passing that close. I’m still after those really dramatic pics, though…