This is just another perspective on the little story found here, since I shot the saga in both digital and film. What you’re seeing is the egg of a ground skink (Scincella lateralis,) right at the moment of hatching. Actually, it takes more than a moment, and this one in particular stayed in this position/state for quite a while, up until I left the camera for seven minutes. During that time away, naturally, the skink emerged completely from the shell. Not only does it take patience to be a nature photographer, it takes more patience than that. “Than what?” you ask. Than whatever you imagine when you think of, “patience.” Seriously.

Just because, part 23

A quick one this morning, an experimental shot done the other night while I was alongside a railing strung with white holiday lights. The Mamiya 80mm macro lens wide open at f4 is what’s largely responsible for the effect, and basic lens traits; the balls are simply point light sources well out of focus. All out-of-focus things have the exact same effect through a lens, but most times they’re not very bright against a black background, so the effect is weak, overlapping everywhere and washing out to a blur. It can also easily be done with dust or mist in the air illuminated by a flash, and then you can say you’re photographing “ghosts” or “orbs” or some such idiocy, if you like.

The only further trick is finding the arrangement of lights that will look best in your frame. This was one of several that I took in two minutes, the one I liked the best.

Scooped again!

I have to do this just to harass the Importunate Mr Bugg, who was with me on the outing this morning and often brags that he’s going to post something first.

We (well, I) spotted a fishing spider, genus Dolomedes, on a rock and went in for the closeup, but noticed in the bright light that it had a bizarre patch of web that it sat across. Fishers don’t make webs except for their egg sac, and that may only be some species, so it seemed odd:

I could see that it had something else in there, probably prey that it was working on, so I went back to shore to affix the macro rig and do a bit more controlled lighting, rather than working with natural bright sunlight as above. And it made a distinct difference, not just in the apparent light direction, but in the details as well:

Ah, that’s it! What we took to be webbing was actually the wings of a dragonfly that was being consumed by the spider, seen at an odd angle. And since it was a big dragonfly, you get an impression of how big the spider was, too. Far from the largest I’ve seen, but not something you want to find in the bathtub, you know?

The same and different

I just received a gout of photos from the blog’s official central US non-correspondent Jim Kramer, from his trip through Wyoming, which I will be featuring here as soon as I can get to it. Unfortunately, this year seems to be trying to prove to me that I can’t set aside much time anymore, so I’m not exactly sure when this will be, but sometime before the Tricentennial, I’m confident…

For now, we’ll stick close to home, as in, home, with a few photos from the yard and over at the nearby pond. It’s not like this blog has a shortage of Chinese mantis (Tenodera sinensis) photos, but I’m following their life cycles so you can too. While they dispersed rapidly after hatching, a small handful can still be found in a couple of areas. One inhabits the Japanese maple that they all hatched underneath, but that one’s been doing quite well in being near-inaccessible to good camera angles even when it’s visible. Another has moved to the other side of the front porch and lives in the small garden there among the daylilies. Once those came in bloom, that mantis was remarkably cooperative one day in posing very nicely against the colorful petals:

I’m not averse to nudging or outright moving an insect to a position that works better for the photo, as you’ll see soon enough, but this one really was as found, aware of me but not fleeing as I played with angles and lighting, so thank Bob for mantis egos. And yes, the left eye is showing a little damage from an unknown cause.

One of the facets of shooting mantises is that you’re never actually sure if you’re shooting the same one on later days or not, even when it’s the same location; they will wander around, and it’s impossible to know just how many really are in a given area. So maybe this is the same one, and maybe not.

I like trying to capture ‘expressions’ from species that, by all rights, shouldn’t be able to display any such thing, and this is one of them, looking off as if it heard the neighbor’s annoying kid falling into the storm drain: not at all surprised, but resigned to the fact that it’s probably going to have to help get him out anyway. Maybe I’m reading too much into it…

It’s been pretty damn hot recently, even at night, and so the misting bottle serves a dual purpose, not just making for a more photogenic subject, but providing a bit of moisture for them to boot. Before this one had a chance to clear the faux dew from its eyes, I captured a moody composition almost by accident, as the light angle and strength wasn’t as originally intended. It made the tight crop pretty interesting though, or at least I think so.

And this next one I was trying to set up for days. The egg sac that they had emerged from (most likely, anyway – there’s always a chance there was another that I remained unaware of,) had been sitting in the same place under the Japanese maple the entire time, but I was thinking that a comparison shot, like last year’s, might be a nice thing to feature. Except that none of the mantids seemed inclined to pose with it, or even be anywhere near it. So when I found one hanging out among the lilies, I simply uprooted the twig I’d tied the egg case to (this being one of three that I’d purchased when I could find none naturally on the property,) and replanted it near the mantis. This sent the mantis into hiding, so I let it be for a bit to calm down again, and perhaps pose helpfully alongside the case. But no, the mantis moved much further away (less than a meter, but still far enough that convincing it to get near the sac would be problematic.) I tried again a few days later when I spotted one again, with much the same results. Then I moved it to a location they seemed to like to visit, but they avoided that area thereafter. Finally, I moved the twig close to one mantis who, later on, was found right underneath the sac itself. So, you say, a simple matter of coaxing the mantis up a little and onto the egg sac, no? Ah ha ha ha ha ha, you naive fool! I say rather callously. You have not done much arthropod wrangling, have you? No, I have a fucking life, you shoot back with ruthless delight…

Getting the mantis to pose by the egg sac for a simple scale shot took several attempts, as the mantis shot past the sac and well up the twig, or jumped clear onto another plant nearby, or jumped from my hands as I transferred it back, but eventually I was successful. So now you can compare this against the pics (and exciting video!) from the hatching. Kind of, anyway – there are no images of the entire sac in there.

The mantis is 60mm long, about six times their length at hatching, and nowhere near adult size yet. By the way, I have to point out the antenna in the mouth, being cleaned (along with its feet) after its icky icky contact with humans. This is quite common in the insect world.

The next one is something I’ve never seen before, and responsible for a vocal “Holy shit!” when I first spotted it. This says a little in itself, since I’m usually making the effort to remain silent when out shooting. You know, good habits and all that.

This is the larva (caterpillar) of a cecropia moth, Hyalophora cecropia, and while it’s colorful that’s not the reason for the cussin’ – it’s huge, the largest caterpillar I’ve ever seen, easily outweighing the hornworms I would find routinely on the tomato plants.

This image might help more than my telling you it was larger in diameter than my thumb and in excess of 100mm long – it’s hard to get an exact measurement of something that stretches and contracts routinely, especially when it starts getting shy and withdrawing its head as much as possible. Yes, those little bedazzler knobs are spiky, but according to the immensely useful BugGuide, they’re not supposed to have any venom in there. I made it a point of not confirming this, partially because when I collected it I hadn’t yet looked it up to determine species, but also because I wasn’t exactly sure I had the right species identification, and also wouldn’t put it past those sneaky entomologists to set up nature photographers like that. There’s always been a bitter rivalry between entomologists and nature photographers*

This image might help more than my telling you it was larger in diameter than my thumb and in excess of 100mm long – it’s hard to get an exact measurement of something that stretches and contracts routinely, especially when it starts getting shy and withdrawing its head as much as possible. Yes, those little bedazzler knobs are spiky, but according to the immensely useful BugGuide, they’re not supposed to have any venom in there. I made it a point of not confirming this, partially because when I collected it I hadn’t yet looked it up to determine species, but also because I wasn’t exactly sure I had the right species identification, and also wouldn’t put it past those sneaky entomologists to set up nature photographers like that. There’s always been a bitter rivalry between entomologists and nature photographers*

In both of these pictures so far, the caterpillar was still reacting to my messing about, and had its head tucked down – the orange knobs are anatomically in line with the yellow ones running down the back, so they’re an indication of how curved the spine would be, if it had a spine. The head is completely hidden in both shots, but we’ll correct that very soon. Not quite yet, though.

This was a typical pose when I was trying for detail shots; any disturbance of the twig caused it to withdraw its head and bring up the forelegs for protection. Or maybe it was raising its dukes for a boxing match – I’m not going to assign motivations to a caterpillar, I’ve been burned on that before.

By the way, between each of its main legs possessing dozens of tiny claws for gripping, and the obvious (if potentially false) threat of those knobs, I simply cut the small branch that it was on to bring it in for photographs. Yeah yeah, I know, don’t disturb nature and all that. The branch was in the process of being totally denuded of all leaves by the caterpillar itself, and sits on the edge of a manmade pond that routinely gets trimmed back and shaped and mowed and so on – seriously, there are bigger things to worry about. Like when the caterpillar finally gets fed up and starts to charge!

Yep, that’s me (not in the pic, of course,) holding steady to get the crucial photos until the very last minute. And did you get the joke about “fed up”? Don’t lie to me, I know you missed it.

Actually, to get this I had to transfer it to a branch out in the yard and then sit and wait for it to feel safe enough to emerge and start moving forward – and then I had to endeavor not to disturb the branch by bumping it with the flash unit, something I failed to do several times, each time sending the caterpillar back into defensive mode. It took a while, I can tell you, and it’s hot out there. You’d better appreciate this.

But my favorite is another semi-staged photo. While waiting with mixed patience for the cecropia to emerge again, I spotted another larva nearby (of the kind typically referred to as “inchworm”) and deposited it on the branch, where it ambled forward and across the feet of the cecropia then paused, perhaps aware that it wasn’t walking on bark anymore. I couldn’t resist the comparison image, but I suppose it helps to know that the giant green mass is another caterpillar and not, you know, a diseased pepper or something…

* You should know by now that any such statement followed by an asterisk means it’s completely false. There’s no bitter rivalry between nature photographers and entomologists – we feel they’re completely beneath notice.

Sunday slide 28

As badass as this guy looks with his knobby pincers and a couple of barnacles, hermit crabs tend to be pretty shy – thus, you know, the shell. This one even chose a particularly badass shell too, that of a crown conch, which I can tell you from experience you don’t want to step on.

Taken in either late 2004 or early 2005 during my time in Florida and held just long enough for photos within my aquarium, this was a pretty sizable specimen of the thinstripe hermit crabs (Clibanarius vittatus) that can be found along the east coast, at least; the shell that it occupied was a little smaller than my fist (which are yuge!) but don’t ask me how to get any kind of accurate measurement of the crab itself. I would have liked it if it had posed against the glass a little further from the corner of the tank so the silicone seam didn’t show in the frame, but that was easy enough to crop out for this dramatic closeup. And anyway, crabs don’t take direction well and this one soon moved on to a less photogenic position. Another that I captured at a different time was benevolent (or oblivious) enough to provide some entertainment for other species in the aquarium.

Podcast: Twps & Boros & USB

And so, at long last, another podcast… but, you know, don’t rejoice yet:

Walkabout podcast – Twps & Boros & USB

Let’s start with the good stuff: Carmen’s Deli in Bellmawr, NJ, where you can get authentic Philly-style hoagies. And other things, too, but who cares? Hoagies, man. Hoagies.

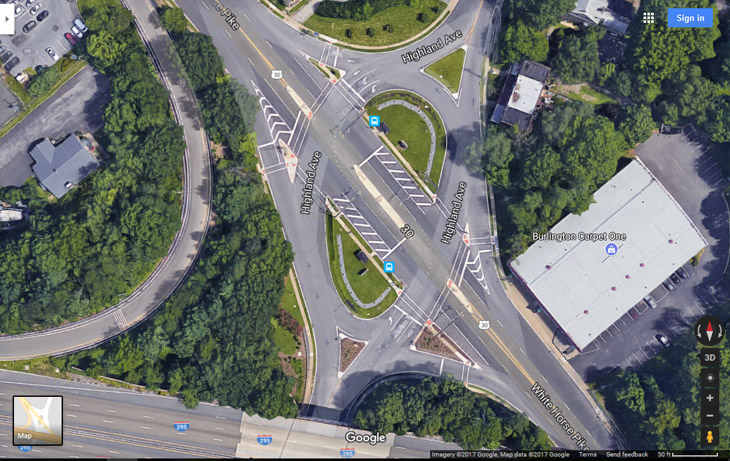

A Jersey jughandle – follow the blue arrows.

If you’re traveling north on E. Black Horse Pike, you have to bear right to go left onto W. Nicholson. Notice, however, that southbound traffic has a (more or less) normal left-turn lane.

Here’s another:

You see, I understand the idea of a traffic circle, which more-or-less regulates without the need for traffic lights (as long as people understand the very simple rule of “yield to those within the circle but not if you’re in it and not if no one is coming” I’m looking at you North Carolinians,) but there are lights at each of these junctions. So how does this improve matters over a simple four-way with turn lanes? Ya got me.

Okay, on to more topical stuff. These are the three components of the macro focusing light that I constructed, for only a few dollars all told.

Okay, on to more topical stuff. These are the three components of the macro focusing light that I constructed, for only a few dollars all told.

At top, the USB power pack, usually intended for recharging smutphones in a pinch, and the 18650 battery that it takes – all I purchased was an empty case, since I already had the battery. It might be best to buy the battery separately so you can get the best deal on the highest milliamp-hour (mah) battery you can find.

In the middle, the USB gooseneck extension, very stiff and easily aimed as needed.

At bottom, the light unit itself, not to the scale of the others but roughly twice as big in this pic – compare the wood grain to the image above it, which is the same stretch of floor. If it helps, the unit is 26mm across, about the diameter of a quarter. And yes, it is bright, and fairly tightly-focused, so ideal for my purposes.

The previous version, a homemade rig, can (kinda) be seen here; it worked, but tended to slip position even with hook-and-loop attachments or rubber bands. Some of this was due to the short gooseneck and the necessity to be close to the lens.

You can see everything in place with the entire macro rig in the opening photo, but highlighted below to point out the components clearly.

The orange zip-tie is removable, and serves to stabilize that end of the gooseneck arm because it doesn’t fit as snugly as needed into the battery pack. But with it, the light remains pointing precisely where needed.

So, how’s it work? Well, the next two images were taken in a pitch-dark room with only the macro light to focus by (manually of course, with the reversed 28-105mm.)

This assassin bug was less than 6mm in body length, making that proboscis 1mm or less, and you can see how short the depth is even at f16 by how quickly the legs have gone out of focus. The stem that it’s perched on is perhaps slightly thicker than a pencil lead.

And this is a tiny shell found during the beach trip – those are grains of sand, fine ones mind you, in the foreground and adhering to the shell. The illumination for both of these images came from the flash unit, but the ability to see them and have the camera at the right focusing distance came courtesy of the new macro light. Yeah, it seems to work just fine.

I still wear a headlamp when out at night just to find my way around and do the initial spotting of subjects, but the macro light comes into play when I’m focusing; as I said, it can be positioned close to the flash unit itself to throw light from the same direction, to give a better indication of how the light will model and where shadows will be thrown. Later on, I might affix another LED directly within the softbox itself, aimed where the center of the flash burst will fall – that way, I know precisely how the lighting will be, and will know when the flash might be blocked by leaves or aimed a little off (which happens more than occasionally.) There are always refinements that can be made.

Oh, what the hell. Here’s another example of Jersey boulevard blight. And yes, I drove through each of these – this one was even under construction. I added arrows to help illustrate directions of travel.

Once again, all of this in ground level, and every place where the lanes cross has a traffic signal – at least twice as many as would be needed for a routine intersection. When the power goes out, this would require a squad of police officers to direct traffic through.

Okay, okay, I’ll get back to nature photography or trashing religion shortly.

Sunday slide 27 (and not)

I am not 100% certain of the maker of these tracks, but it’s one of two species, and I’m pretty confident that it’s a North American river otter (Lontra canadensis) – the other possibility is a raccoon. There are subtle differences between the two, and some obvious ones like size, since an otter can be many times the mass of a raccoon, but my memory of the exact size is gone and I have nothing in the image for scale. This week’s slide was taken in 2003 in Florida, on the banks of the Indian River Lagoon, where the early morning sunlight played across the trail in a dramatic way. Both species would use the lagoon to find food at night, but raccoons would forage on the shore and in the shallows while otters would dive in and chase fish right in their element. Let’s just say ‘otter’ and be done with it.

Low-angle light is best for capturing things like animal tracks, as well as other textures, and the yellow sunrise beam provided a nice dramatic element. Of course I had to take this one.

Now, typing all that reminded me of some other images, and I went looking, but they’re not slides and don’t have the optimum light angle. At some other point in time in the same location (I ventured out to the area a lot,) I found an unmistakable otter trail, this one showing clear evidence of a sizable capture. It has to be a pretty big fish for an otter not to be able to carry it, and drag it along instead.

This was, in fact, taken at the same location as this series, so you can see that big fish were certainly available. The trail disappeared into a thicket impenetrable to me, and there was no chance of following it to see if the lucky otter was still working on its meal. Or passed out from gorging.

The obligated abstract

Okay, no, it’s really still June, and not eight hours into July, so my month-end abstract is still on time. It’s was just… server issues, yeah, that’s it, server issues that prevented this from posting when I told it to.

Okay, no, it’s really still June, and not eight hours into July, so my month-end abstract is still on time. It’s was just… server issues, yeah, that’s it, server issues that prevented this from posting when I told it to.

[No, I am not going to back-date a post just to look like I’m maintaining a schedule.]

And, as might be gathered from the previous few posts, I’ve been doing little shooting and exploring this month, so I didn’t have a whole lot of choices for abstract compositions that were taken in June, and I cheated a little by tightly cropping a “normal” shot (for me) to create an abstract. Maybe I should just stop the monthly posts if I can’t fulfill them properly…

But then I’d miss the opportunity to present an image that you’ll suddenly remember when you’re trying to fall asleep. I can’t take away my fun like that.

If you’re flummoxed by this one, all you need to know is that it’s a variation of one of these, not far enough back that it even looks unfamiliar; a variation that had too deep shadows on one side and so I cropped it very close to try and make it confusing. A cheap trick, I know, but you already understand that’s not beneath me at all, so keep quiet. You knew what you were getting into when you came here again.

Sunday slide 26

And so we reach the halfway point in the year, at least as far as Sunday slide posts go. This week’s offering comes from April 2006, as a collection of wheel bugs (Arilus cristatus) hatches from an egg cluster affixed to the branch of a tree. I credit this capture to James L. Kramer, who has made a few appearances on this blog – he didn’t take this image (he got plenty of his own,) but had the egg cluster in his yard and was monitoring it closely, notifying me when the hatching had started to take place, and luckily I was available at the time. To give a idea of scale, the entire egg cluster spanned about the width of a dime, so these guys are pretty small. The extraction from the egg case, unlike (for instance) the emergence of adult parasitic wasps from their cocoon, takes place over several minutes with little visual activity – occasionally a leg breaks free, and at the very end the action is breathtaking as the insect draws completely free from the case (I’m being sarcastic, since it still appears to be in slow motion,) but a candidate for video this ain’t; even time lapse photography would show long periods with minimal movement.

With all the macro work I do now, I look at this and shrug, not terribly impressed. The Sigma 105 macro was a fine performer, but at this magnification it was pushing the limits, and I can achieve a whole lot better now with some pretty esoteric equipment. Ah, the difference eleven years will make…

For comparison, some pics of a juvenile wheel bug can be seen here, and an adult here – at hatching, they are perhaps 5mm in body length, while the adult at that link was 35mm, so there’s quite a bit of difference in just a few months, much like the mantids. Which reminds me that we need an update on them soon, lest I tarnish my reputation.

Fill frogs

I have been trying to get to a couple of posts, including possibly a podcast, for quite a while now, and just haven’t been able to get my shit together. So for now, because I feel guilty and inadequate, I’m going to do a quickie to feature a few of the amphibians I’ve found in the past few weeks.

I have been trying to get to a couple of posts, including possibly a podcast, for quite a while now, and just haven’t been able to get my shit together. So for now, because I feel guilty and inadequate, I’m going to do a quickie to feature a few of the amphibians I’ve found in the past few weeks.

This particular image goes back to the beginning of May, before the beach trip, and wont even be the oldest one. A Copes grey treefrog (Hyla chrysoscelis) was found one evening perched atop a fence post, and even though I have a lot of such photos in my stock already, I went slightly fartsy to use the line of posts in the composition. Such efforts, I know. I could only easily get to this side of the fence, the other being a bit overgrown, and initially the frog was facing the other way and thus continuing the emphasis of the fence posts to the right, but it turned around as I was locking focus, because of course it had to.

On a brief visit to the NC Botanical Garden in late April, just about everything that I saw (that wasn’t vegetation) was frogs, toads, or lizards. In a small pond liner, a pair of American toads (Anaxyrus americanus) were busy producing the 2018 models.

I can’t believe I was unaware of this until recently, but frogs and toads do not reproduce through penetration, since the males have no penises; instead, they mate much like fish do, with the female throwing down a few dozen/hundred eggs and the males basting said eggs with sperm – yeah, right in the same waters I tend to wade in (rumor has it they poop there too, but this could simply be a filthy lie.) There really isn’t a reason for the male to latch on like this, but I suppose the proximity greatly increases the chance that his own sperm will be the ones to fertilize the eggs, though I’ve seen stacked males more than a few times in the past, so if you’re a tadpole it’s probably best not to ask who your father was.

Which leads to a more recent shot, taken back on the 16th during heavy rains, of which we’ve had out fair share and then some. Hearing the grey treefrogs once again calling in the backyard, I ventured out and found not just a lone specimen on the fence posts like above (though probably not the same individual,) but also this pair, with the male at the ready to do his duty once the female actually decided on a place to deposit her brood.

Given their proximity to our own backyard pond liner, it’s likely the female was considering this as a place to deposit her eggs, but near as I can tell she didn’t decide favorably, because I have seen no evidence of such within.

There has, however, been evidence that other species have been doing the nasty there, since we had several sizable tadpoles hanging out. They would dive for the bottom and out of sight whenever I came into view, so I would get only a brief glimpse at most, but I was fairly certain that at least one was sporting the full complement of legs. Eventually, I captured one that showed this transitional stage, and did some portraits at the same time that I was getting confused by the water beetle eyes.

This one, a green frog tadpole (Lithobates clamitans) was still largely convinced to remain aquatic, but from time to time during the session it seemed to recognize that maybe, just maybe, it didn’t have to stay in the water. It was active enough that getting the quality shot was a bit challenging, and even interfered with the beetle images that I was attempting by blundering through the frame once I finally got the beetle to hold still near the glass, so there’s a little tip for you when using a macro tank: one specimen at a time, especially if they’re active.

Naturally, after I finally got these shots, then one of the quadrupoles decided it would bask at the pond’s edge in bright sunlight and completely ignore my presence. I like this because it shows the full-length tail, something that would soon begin to shorten before vanishing entirely.

Naturally, after I finally got these shots, then one of the quadrupoles decided it would bask at the pond’s edge in bright sunlight and completely ignore my presence. I like this because it shows the full-length tail, something that would soon begin to shorten before vanishing entirely.

Not very long after getting these shots, we had torrents of rain over a period of several days, and the tadpoles seem to have all vacated the pond now. There are some curious detail shots that I got before this occurred, again taken with the macro tank, that may show up here sooner or later.

Just yesterday, as I was catching up on some garden work, I found this tiny toad in the yard and brought it up to the porch for a quick couple of pics. It was determined to face away from me and head towards the edge of the shallow pan that I used as housing, so I had to almost-continually keep spinning the pan to try for the head shot, and I couldn’t tell you which of us was getting more frustrated, but it worked eventually.

Now, I say toad, but I’m not absolutely sure about that – it remains unidentified, and I’m judging only from the texture of the skin and lack of other identifying characteristics, but it was also quite small, a modest percentage of the size of an adult American toad, so might have been one of the chorus frogs or ‘peepers’ that inhabit the area. I was smart enough to introduce the millimeter scale for some of the shots.

So, about 12mm in overall body length, which as The Girlfriend pointed out, is literally thumbnail size – she’s always delighted to see the tiny cute ones.

She was also delighted to see the next, which I forwarded to her while she was at work, and she promptly made it her computer background image – I think it closes the post quite well. For a few days, a green treefrog (Hyla cinerea) chose to perch on the pokeweed plants in the backyard, finding a plant with a sturdy stem and the closest hue to its own natural coloration. Despite the macro flash effect, which always makes the backgrounds dark, the clues that this was taken during the daytime are the small pupils and the generally sleepy appearance of the frog, which are of course nocturnal.

By the way, I have to point out that I’m pleased with the simplicity of lines in this image. While I was concentrating on the portrait angle like usual, the stems worked very well in the composition, helping to focus attention. Not like you’d miss the frog anyway, but it still works, in my opinion. We all know what that’s worth, so let’s not go there…