Like many people – actually, a ridiculous number of them – I grew up with this idea of being a “friend” to the animals. I can remember, from a very early age, going on a camping trip and sleeping in a pop-up camper, wishing (now that I was out in nature) that a raccoon would slip into the camper and curl up on my back to sleep; this was my way of thinking that I was “in tune” with the animals.

It probably had a lot to do with how I grew up. My parents and grandmother (whom I never met) were some of the founding members of the local Animal Welfare Association and worked with wildlife rescue – in fact, one of our kayaks had an AWA identifier on it – and my older brothers were Boy Scouts and had plenty of tales of wildlife encounters; one of them raised snakes and picked up wild skunks for amusement. Without the obvious retribution, I might add. So while I was too young to participate in any such shenanigans, I was still immersed in the environment and mindset. I can remember, very distinctly, being along with my dad when he was out trying to spot an escaped flamingo in the marshy area of a local pond, in south Jersey where I grew up. He saw it and tried pointing it out to me, but at that time I had not yet been diagnosed with Ludicrous Myopia, and as he attempted to direct my gaze to the subtle pink shape moving at the waterline, all I could see in the dusk were the taillights of the cars on the road behind it; I was trying to figure out how flamingos could glow as brightly as that.

Later on in my adolescent years, I began reading nonfiction books about wildlife rehabilitation and encounters, such as the Durrell books and Frosty: A Raccoon to Remember. These started to give me a more realistic impression, that wild animals have their own habits and attitudes, for want of a better word, and these do not revolve around being buddies with people – even when they’re raised in a human environment. You don’t turn any animal into a “pet” just by getting them when they’re young. Sure enough, some animals can be habituated to view human contact as non-threatening, perhaps even beneficial, but this does not translate into domestication, which takes many generations. We’ve had cats and dogs for thousands of years now, and still find that they have specific behaviors that don’t disappear.

But it was funny. Far from being disappointed, I was fascinated by the aspect of working with animals, even when I recognized that I was unlikely to do so routinely, much less for a living. But soon after moving to North Carolina, I got involved with a local humane society that performed animal rescue services, including wildlife, and was soon immersed in wildlife rehabilitation. While I attended all of the volunteer workshops for the species that could be found in the area, I received specific training for raptors at a dedicated facility in the state, the Carolina Raptor Center outside of Charlotte. This allowed me to work with the injured birds of prey that came through our door, and I started noticing little details.

This very trait may owe its origin to the Doctor Doolittle stories by Hugh Lofting, which I read in my adolescence. The good doctor is taught how to ‘speak’ with many different species by his parrot, and (to Lofting’s credit) she indicated that most animals communicate through body language and behavior, rather than through sound – accurate to a degree at least, because while it serves a purpose of indicating mood and intention at times, it likely isn’t intentional or conscious; that’s just the way things are. However, after introducing this concept, Lofting appeared to have forgotten about it forever thereafter…

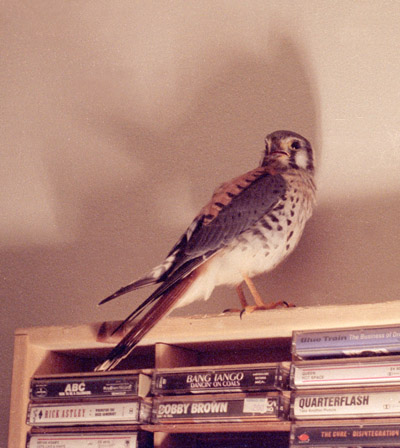

[Time out for a favorite but distantly-related rehab memory.] We had an adult American kestrel (Falco sparverius) in once, possibly from an encounter with a car but with no broken bones. Nonetheless, it was unable to fly, and for birds that depend on flight to obtain food, this is often a death sentence. It came to us in poor condition, probably not having eaten for several days, and we set upon bringing it slowly back up to speed; it has to be done carefully, because a full meal when the condition has dropped that low can simply kill the bird.

After a couple of days of fluids and blended proteins (a vitamin supplement and the soft parts of mice, yes, blended – rehab is not for the squeamish,) the little falcon should have been able to take solid food on its own, but it was refusing and being stubborn. I still worked the desk in the busy shelter and couldn’t devote a lot of time to the task, so I decided to take the bird home in a carrier and tackle the task there when time was more lenient. Kestrels are small for raptors, a little bigger than an American robin or thrush, and that evening I wrapped it firmly within a small towel, to immobilize the wings and talons while keeping the head and beak free. I had prepared several choice sections of mice on a small plate, and grasped one in a set of forceps and attempted to ease this into the bird’s beak. It remained just as stubborn and was having none of this, and I struggled with this task for quite some time – failing to notice that the towel was slowly loosening.

At the same time as the raptor work, I was also close to the dog training programs, and learned how a lot of dog behavior ties in with the pack dynamic, the necessities of interacting with other dogs as part of the social structure that the canids have. This carries through into how a dog interacts with a family, and illustrates a blind spot that we humans often have: we like to think of other species in our own terms, like “friend” and even “obey,” failing to recognize that other species have their own interactive structures (or lack thereof) and see everything in those terms – a mutual blind spot, if you will. Seeing things from this pack perspective helps us to realize that, despite our best efforts at training, some things will fall outside of the reward and status structure that we use as training methods, such as when a squirrel appears. This is why I often smile indulgently when someone tells me their dog can be off-leash because it is on “voice-command” – there really is nothing that completely overrides some basic instincts, loathe as anyone might be to admit it.

Throughout this, I was building my photography skills and starting to do more and more wildlife photos. By now, I had come to realize how other species all have their own dynamics, reflections of the factors that are key to their survival. I would watch the seagulls competing over perches, and recognize which one was considered the ‘alpha male.’ I noticed that a lot of species could be approached obliquely, allowing someone to get closer as long as they did so on a diagonal. I had known for a while that the mere appearance of humans isn’t as disturbing as sudden movement but found, to my delight, that mimicking the species’ behavior could quell their distrust to some extent.

And I was involved in critical thinking, and studying evolution, and no small amount of philosophy of the mind. This was the latest of steps towards my current perspective, and hopefully not the last. Evolutionary psychology is the concept of how the behavior of species is dependent on the same selection that built their body structure, and how animals (including us) have predetermined importance, emphasis within the brains and emotions themselves, that reflect the survival pressures faced. As such, most species have no reason to be “friends” with humans in any way; if they have any social functions at all, it’s in support of their own species, because that’s what evolution favors. You see, we have the concept of friends because our tribal interactions were part of our development, group hunting and shared shelters and farming and so on; we thrived with an interactive and cooperative community. Some other species have variations, but they’re specific to their own needs, and rarely bridge the gap to a species other than their own, since there’s just no need. And this may apply especially to bridging over towards humans: we’re pretty good about hunting other animals as desired, and often don’t see much benefit towards mutually cooperative relations. While there’s a peculiar trait within us that fosters the idea that we may get a worthy companionship with species like dogs and cats, they do not necessarily have the same ideas; we cannot really say how they view us. But this little trait of ours becomes more than problematic when we apply it towards wilder species, thinking we’re in tune with bears or that if we’re non-threatening to the deer that visit the backyard that they’ll feed happily from our hands.

Which is where this whole post is going. With what little impact I have, my explanations and advocacy for more realistic expectations from wildlife, my pointing out behavioral traits to students and occasionally just passers-by when shooting in a public place, my efforts to rehabilitate animals without any belief or desire that they would even view the situation fondly (much less without terror or loathing,) I have become more of a “friend” to the animals than I imagined in my youth – this time defining it as a mutually-beneficial relationship. Because yes, I get something out of it as well, the fascination in working with other species, the good feelings from seeing previously debilitated animals released back into the wild, the pride in getting some shot that illustrates a trait or even just provides a mistaken impression of ‘personality’ or ‘mood.’ We should never expect to be buddies with another species, even when it can happen with domesticated animals – the wild ones have their own ideas of proper behavior, and will remind us of our mistakes, sometimes in very unfortunate ways. Anyone that I reach when I say, “Respect them, and maintain safe distances and responsible behavior,” becomes more beneficial to them than anyone who thinks they’re bonding in some selfish and naïve way.

When that kestrel up there was released, it flew to the top of a nearby telephone pole and perched there for about two minutes, producing the most complicated serenade that I’ve ever heard from a raptor, before flying off and vanishing into the distance. And by “serenade,” I’m being poetic but unrealistic: I have no idea what the purpose was, but I’m pretty damn sure it wasn’t intended as any communication to me – that’s not what bird song is for. Far too many people would have viewed it differently, and could have believed that I was being thanked, or perhaps even scolded for the captivity, but those are human ideas, and should go no further than us.

This Saturday, May 13th, is National Migratory Bird Day, and I know that’s got you as excited as this guy here. I will be on the road at least part of that day, so I don’t know whether I’ll get the chance to do any appropriate shots or not – we’ll just have to see. But I figured I’d get a little head start on it, because I have the time today and a pair of semi-cooperative subjects.

This Saturday, May 13th, is National Migratory Bird Day, and I know that’s got you as excited as this guy here. I will be on the road at least part of that day, so I don’t know whether I’ll get the chance to do any appropriate shots or not – we’ll just have to see. But I figured I’d get a little head start on it, because I have the time today and a pair of semi-cooperative subjects.