We once again find ourselves at Freethinkers Day, and I’ve featured it a couple of times before, so you can also check those out for my perspective and recommendations. Frankly, I’m more in favor of calling it “Thinker’s Day” instead, or perhaps, “Are You Sure? Day,” because this is the part that really needs encouragement, as I’ve been reminded recently.

Something that is rampant, especially within this country, is mistaking an opinion, especially a strong and voiced one, with a reasoned opinion; we assume, far too often, that if someone is firmly, even emotionally behind some conclusion or viewpoint, that they’ve done the legwork and have good reason to be – even that they have exercised good reason. But the percentage of times that this is resolutely not the case is staggering, and I suspect there’s a far greater correlation between someone being non-committal or only mildly in favor or a particular viewpoint, and actually having thought it through. Because, let’s face it: the world is not full of absolutes, easy distinctions, or binary choices; it’s full of huge grey areas, and in fact, our reliance on absolutes, binary decisions, and polar opposites is not reflected in just about any area of real life. Forget good and bad, or good and evil, forget right or wrong, forget every “this or that” choice you might believe exists, because they simply don’t. Everything is a spectrum, and every worthwhile decision depends on careful comparison and aiming for the greatest benefit or the least harm, preferably a combination of the two. Easy answers are immediately suspect, and likely ignoring countless real-life factors; clear demarcations are likely far fuzzier and indistinct, when examined, than ever suspected.

The firm opinion is usually (not always – again, grey areas) the realm of a strictly emotional response, settled on because the holder likes some particular aspect of it, and often bears no critical review behind it. I’m no sociologist, but I strongly suspect that many, perhaps most, decisions are made this way, and confirmation bias comes into play when finding the ‘rational’ justification for it afterward. “I hate cheesecake,” may start with tasting a particularly bad example, and then gets followed with, “It’s fattening,” “It has too much sugar,” “It exploits cows and dairy,” and, “It’s really a pie.” A frivolous example perhaps, but you can likely spot any number of firm opinions that people hold that have begun in exactly this manner.

Something to remember, too, is that emotions are mere guides to survival, simple internal influences that resulted in pushing us forward better than the alternative at the time; they are not exact, they are not dependable, and they are not useful or even accurate in every circumstance. Just like every other animal, we have them solely because they worked just enough to make it through the process of natural selection, but nothing in that process actually produces perfection. Think of deer, that have a habit of standing still in circumstances of questionable danger so as not to attract attention by noise or movement. This works for just enough of the time to make it through the selection meatgrinder, but fails when it comes to the semi-truck bearing down. And as much as we’d like to believe we’re something special and totally unlike every other species on the planet, we spent the vast majority of our development dealing with the same kinds of dangers and the necessity of quick decisions, and that’s what our emotions reflect. That’s all they reflect. While there are certainly circumstances where they work just ducky – we wouldn’t have them if they didn’t – this in no way should be taken to mean that they’re dependable or reliable. And the very aspect that we believe sets us apart from all the other animals, our reasoning and rational brain, is what needs to be exercised to get us safely past those circumstances where the emotions fail.

Another emotion that traps us continually, and gets exploited all the time by those who understand it, is conformity. We feel the need to fit in, to be socially accepted by those around us, because our ancestors survived by being tribal/village/community-based instead of individually. But this also means we very easily fall for being just as stupid as those around us, mistaking this internal drive for the assumption that they all know what they’re doing, and, “this many people can’t be wrong.” Yet here’s an easy, quick decision for you, one that really is dependable: Yes. Yes, they can. History bears this up repeatedly.

So that’s my suggestion of an exercise, for today at least but really, embracing critical-thinking means we do this as often as possible: Stop and ask ourselves, But is it really? Did I find the best conclusion, or simply the one that struck me as ‘Right’ at the time? Take a moment or three to think about whether or not some conclusion, some opinion, some decision, can really be supported rationally. And the much harder part, to seek out the other side of the coin (or again, not settle for such a binary aspect,) and argue against ourselves, the devil’s advocate position, to see if our viewpoint still holds up. It can be tricky, for sure.

I’m not suggesting being in a perpetual, existential state of questioning everything, because then we cannot make decisions at all – merely that we seek out those circumstances where we settled on some viewpoint or conclusion too quickly, without due consideration. The question is, how many can we actually find?

Here’s another thing to remember that goes hand-in-hand with it all: It’s okay that we change our mind. It’s commendable, actually; this is growth, this is improvement, this is increasing intelligence, this is becoming a bigger person, and it’s even (much as this seems like a counterpoint) an aspect of humility. Why stagnate perpetually with a decision or viewpoint that obviously could be better, in favor of… what, exactly? Not admitting that we’re wrong is not the same as not being wrong, and is often the exact opposite. Own up to it, get on top of it, and move forward. And confidently, forthrightly, admit to it as needed – more people need to see this happening to understand that it really is okay, because, goddamn, do we have far too many people that cannot.

And while we’re at it, enjoy a piece of cheesecake.

Here’s an animated gif (pronounced, “JEM-uh-nee“) comparison of two images shot back-to-back on a tripod, just different apertures. No real macro work here, nor specifically close, but the distance between elements is large enough. [I also used a handheld flashlight for one of the frames, which added highlights that did nothing for the image.] This begins to show another factor that affects bokeh, which is background contrast: the varying brightness of the leaves back there produces more blobs, and since the difference in distances isn’t as great as the image above, they have more distinction, not overrunning each other as much. For really nice smooth bokeh, the background should be as low contrast (in brightness or color variation) as you can achieve. This would have made the focused, foreground leaves stand out more and have a more distinct demarcation between them and the background.

Here’s an animated gif (pronounced, “JEM-uh-nee“) comparison of two images shot back-to-back on a tripod, just different apertures. No real macro work here, nor specifically close, but the distance between elements is large enough. [I also used a handheld flashlight for one of the frames, which added highlights that did nothing for the image.] This begins to show another factor that affects bokeh, which is background contrast: the varying brightness of the leaves back there produces more blobs, and since the difference in distances isn’t as great as the image above, they have more distinction, not overrunning each other as much. For really nice smooth bokeh, the background should be as low contrast (in brightness or color variation) as you can achieve. This would have made the focused, foreground leaves stand out more and have a more distinct demarcation between them and the background.

This is an extreme example, and even though unrecorded in the info, I recall this lens – this is the Mamiya 80mm macro, likely with the coupled extension tube, wide open at f4. The color of the mantis matched the background so closely that there is only the faintest difference in hues between them, and the depth so short that everything went out of focus within a very short distance. The bokeh now provides only the barest of impressions of the back and the forelegs, producing a quite abstract image very simply. Luckily, most of the face of the mantis was flat to the camera so it wasn’t going out of focus from mouth to antenna too badly. But you can’t get much smoother bokeh than this.

This is an extreme example, and even though unrecorded in the info, I recall this lens – this is the Mamiya 80mm macro, likely with the coupled extension tube, wide open at f4. The color of the mantis matched the background so closely that there is only the faintest difference in hues between them, and the depth so short that everything went out of focus within a very short distance. The bokeh now provides only the barest of impressions of the back and the forelegs, producing a quite abstract image very simply. Luckily, most of the face of the mantis was flat to the camera so it wasn’t going out of focus from mouth to antenna too badly. But you can’t get much smoother bokeh than this.

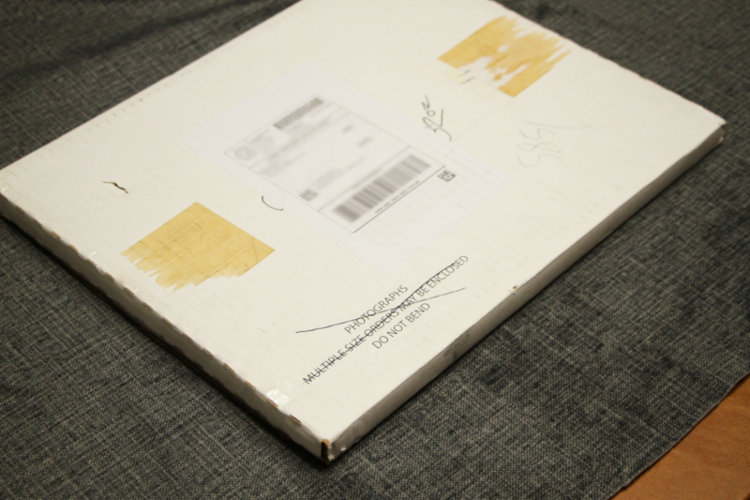

All four prints had two kinks each in them, and if you haven’t had to deal with this yet, kinks in photos simply don’t come out. They will be visible as soon as the light angle gets right, and attempting to flatten them out virtually never works and you can damage the print by trying. This is an extremely well-known hazard of shipping prints, and as such, any reputable company takes steps to ensure that this cannot happen.

All four prints had two kinks each in them, and if you haven’t had to deal with this yet, kinks in photos simply don’t come out. They will be visible as soon as the light angle gets right, and attempting to flatten them out virtually never works and you can damage the print by trying. This is an extremely well-known hazard of shipping prints, and as such, any reputable company takes steps to ensure that this cannot happen.