Yeah, I know, it’s a really poor posting schedule for the beginning of the year, and I’d like to say that there’s a good reason, and I will because I’m good at indulging myself, but honestly, there isn’t. It’s been fairly cold with little to see here save for the same ol’ subjects that aren’t doing anything new, though I do have a few video clips to finish off – should have done it last night but ran out of steam.

Then this morning, there was a decent fog, lifting even as I got out to do something with it. So we’ll start with a couple of pics.

While the fog left behind plenty of moisture, there wasn’t a lot to leave it on that was photogenic, so I settled on the almond tree and its spiderweb rigging, likely always there but invisible without these conditions. Key, naturally, was getting them against a dark background.

It showed a little better on the weathervane.

It kind of looks like the air has been so still even the spiderwebs haven’t been disturbed, but that isn’t necessarily the case; none of the strands appear to stretch between the movable duck sail and the fixed compass cross. This is all 3D-printed, by the way, and I’d say it was my own design but it’s only my own modifications of someone else’s designs. Still, I should probably upload it…

But we do have one image of the fog itself, before it vanished entirely.

We need a comparison shot for this, though. The pond has been distinctly higher for the past couple of months, to the point that the channel to The Bayou is no longer a channel, but a broader flood plain as seen here. We compare it to a shot from not quite a year ago after the snow:

This is sized and cropped to the same perspective; the channel that the ducks and geese use passes in front of those two trees close together on the left. Which brings us to the start of today’s saga, since while doing some brief video clips overlooking the pond, I noticed that a soda bottle was floating near the edge, getting in the frame. I’ve been seeing one or two cycling around the pond recently, due to the higher water level (more on this in a moment,) but since this was close enough to the edge I decided I was going to get it out of there. Donning the mud boots, I went out with a small net and snagged it, then went after two more, though one of those was just far enough out that I flooded the boots. While I was doing this, The Girlfriend took another net and snagged some other trash that she saw, bringing up a little surprise as she did so.

Saying that this is the largest fish I’ve seen in the pond gives you an idea of the conditions; the pond is fed primarily by rain runoff and possibly a small spring, and the channel connection at the southern end was narrow and quite shallow. So what we have are minnows, and since the pond is shallow, I suspect any larger fish that might wend their way into the area get found by herons pretty quickly. Based on illustrations here, I’m going to tentatively say this is a young smallmouth bass (Micropterus dolomieu,) especially because it lacks the black gill flap of the bluegill, but my confidence in this identification is fairly low. Nor do I really care – I have little interest in fish, and absolutely none at all in fishing.

Now that my boots were flooded, however, I decided to venture into The Puddle, the tiny little pond that sits in the middle of the backyard, because there’s an overgrown fountain and millstone in there that we’ve been meaning to clear off. The Puddle is bordered by an American tulip tree, a pin oak, and a few bald cypress, so the debris collects easily within, and even though the fountain and millstone were only a few meters away, they were mostly obscured. I got in enough to fish out the fountainhead, bringing it out for cleaning – we’re probably not going to restore the fountain since the water level fluctuates too much.

That’s The Puddle in the background, so you can see it’s not exactly stockable or swimmable, and that little patch of teal right behind the frog’s back is the remains of the pump filter – underneath it sits the millstone (which is going to remain since it probably weighs a few hundred kilos.)

The day was quite warm – I was out only in a T-shirt – and having already gotten soaked and dirty, I figured it was time to tackle a couple of other tasks. The first was raising the wood duck box a little higher, which required the kayak and the ladder (see that link above if you haven’t already.) Both have to be lugged through the woods to the opposite side of the pond, and placing them is tricky, as is actually going out there to raise the box, so it had been waiting for a while until we got psyched out for it. And then, having finished with that, it was on to part two, which was cleaning out the creek a bit.

Here’s the scenario: While the pond forms the edge of nearly the entire backyard, Walkabout Estates actually encompasses a thin band of land on the far side of it, bordered by a creek; this was where we first saw the beavers. The creek runs under the road that you hear in the background of every outdoor video, and as such (and being in the southern United States,) it collects a shitload of trash from the various inconsiderate inbred fuckholes that toss their garbage out there since, you know, we’re not civilized enough to actually have trash collection here (that’s sarcasm – we do, every week.) The pond and the creek aren’t connected, per se, but there’s a small inlet crossover into a tiny channel that eventually ends up in The Bayou, though the flow through this is infinitesimal. However, with the water level up, there apparently is a little more back-and-forth happening, and a little bit of the trash from the creek makes it into The Bayou and then upwards into the pond. I’ve been looking at the trash in this creek ever since we moved here, vowing to one day get the kayak into it and collect as much as I could, and today became the day.

The sides of the creek are shrouded by undergrowth over a large percentage, and we weren’t prepared for the volume of trash that it held. I carried a small net and several trash bags in the kayak, tossing each onshore as I filled them, while The Girlfriend worked with a larger net from shore, fighting through the bamboo and old greenbrier vines. Between us, we filled six bags, but this was hardly a dent in the amount that the creek held. It was especially discouraging to get down a little ways, beyond what I’d ever been able to see from shore, and find what was waiting there:

This is perhaps not quite as bad as it appears, since the creek has minimal draft and thus minimal flow, and the log forming this natural dam may have been collecting this for quite some time; I know I’ve seen the tire in there go up and down the creek by small increments over the past year. There is at least one other trash-collection session awaiting us, probably more, and then we’ll see how fast it accumulates again.

By this time, however, we were both exhausted, and in fact left the full trash bags stacked to be brought up another day. After pulling the kayak back out, I took the opportunity to register the evidence of beaver activity that had grown since I’d last been in that stretch (which has been longer than it should’ve, really):

That’s quite a job, and shows just how high a beaver can reach when standing on their hind legs. We have another closer look:

This is the first time I’ve been in the sandals since early November, I think – feels good. The tree will survive this damage easily, by the way – there are several others that show the same treatment, obviously years ago. These four images were all taken with the waterproof Ricoh WG-60, the only camera I’ll take out in the kayak, definitely very handy to have.

All of that pushed back several of the other tasks that I’d planned for myself today, especially since we both needed to clean up extensively once we returned, and we both felt inclined to nap after that. A couple of those tasks will be tackled once this posts, but for the rest, tomorrow’s another day. I just didn’t want you thinking, with the lack of posts, that I was getting lazy or something…

This is, naturally, evidence of a fairly recent shed, only he’s never managed to dislodge it completely and possibly has no motivation to, since it’s about as out-of-the-way as it can be. But I noticed something odd in the old skin, shown here, an oval pattern which didn’t seem to fit. Now, if it were a snake, I’d say this was an eyecup, since snakes shed their eye coverings with the rest of their skin, but anoles don’t do that. Ear, perhaps? No, that’s an opening too and should only be a hole in the skin. Then piecing things together along that spinal ‘seam,’ I realized it was probably from the parietal eye (I’d always called it the pineal eye, another term for it but apparently not the preferred one,) which is a simple light-sensing organ centered nicely on top of the skull, not in focus in the image below but sitting just opposite in the frame, in between the grey areas just aft of the proper eyes:

This is, naturally, evidence of a fairly recent shed, only he’s never managed to dislodge it completely and possibly has no motivation to, since it’s about as out-of-the-way as it can be. But I noticed something odd in the old skin, shown here, an oval pattern which didn’t seem to fit. Now, if it were a snake, I’d say this was an eyecup, since snakes shed their eye coverings with the rest of their skin, but anoles don’t do that. Ear, perhaps? No, that’s an opening too and should only be a hole in the skin. Then piecing things together along that spinal ‘seam,’ I realized it was probably from the parietal eye (I’d always called it the pineal eye, another term for it but apparently not the preferred one,) which is a simple light-sensing organ centered nicely on top of the skull, not in focus in the image below but sitting just opposite in the frame, in between the grey areas just aft of the proper eyes:

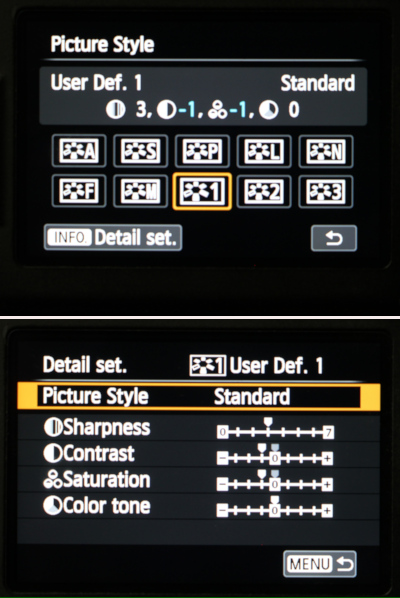

There are three User Defined Modes here, allowing the user to save the parameters of Picture Style, Sharpness, Contrast, Saturation, and Color Tone to a given preset that can be made active in moments. Here, my Definition 1 shows Standard style, neutral Sharpness, but lowered Contrast and Saturation, and then neutral Color tone. And the reason for this is, I shoot primarily in natural light; sometimes brilliant sunlight with high contrast and the ability to overpower colors and bleach out highlights, and sometimes full overcast with its very low contrast and weaker color response. So I have a couple of presets to counteract these traits, which could otherwise exceed the limits of typical digital photographs. This setting is what is used in those bright sunlight conditions, reducing the contrast and saturation to help keep the color response and dynamic range (the range of brightness from full black to full white) within control. You’ll notice, however, that I’ve only adjusted by one ‘step’ on these, while three are available. In my experience, having the camera make more drastic adjustments can often result in images that begin to look unrealistic, yet you may find that your own uses benefit from higher settings. Something to remember: if the camera saved the image file with certain adjustments, you likely won’t be able to reverse these if they’re too strong. And at the same time, if the sunlit snow bleaches out to pure white, you’re not bringing detail back into the image. I have a decent grasp of digital editing and can make adjustments if needed, so I tend to prefer keeping the in-camera effects to a minimum, but again, season to your own taste.

There are three User Defined Modes here, allowing the user to save the parameters of Picture Style, Sharpness, Contrast, Saturation, and Color Tone to a given preset that can be made active in moments. Here, my Definition 1 shows Standard style, neutral Sharpness, but lowered Contrast and Saturation, and then neutral Color tone. And the reason for this is, I shoot primarily in natural light; sometimes brilliant sunlight with high contrast and the ability to overpower colors and bleach out highlights, and sometimes full overcast with its very low contrast and weaker color response. So I have a couple of presets to counteract these traits, which could otherwise exceed the limits of typical digital photographs. This setting is what is used in those bright sunlight conditions, reducing the contrast and saturation to help keep the color response and dynamic range (the range of brightness from full black to full white) within control. You’ll notice, however, that I’ve only adjusted by one ‘step’ on these, while three are available. In my experience, having the camera make more drastic adjustments can often result in images that begin to look unrealistic, yet you may find that your own uses benefit from higher settings. Something to remember: if the camera saved the image file with certain adjustments, you likely won’t be able to reverse these if they’re too strong. And at the same time, if the sunlit snow bleaches out to pure white, you’re not bringing detail back into the image. I have a decent grasp of digital editing and can make adjustments if needed, so I tend to prefer keeping the in-camera effects to a minimum, but again, season to your own taste.