… but you wouldn’t believe it from looking at an awful lot of drivers today.

Sorry, this is way off topic, but coming right after getting rear-ended in a stupid and pointless manner, I just feel the need to point some things out. I also walk alongside the road semi-regularly, and observe the really poor handling of pedestrians and bicyclists too, at least in this area. Seriously, driving safely really isn’t a difficult thing at all, and I can’t fully fathom why it seems to elude so many people. So here are a few little items just to kind of get the reminder out there.

First off, of course,

Put the fucking phone down. You are responsible for a large, heavy vehicle that, even at slow speeds, is capable of doing a shitload of damage. It deserves your undivided attention. There is absolutely nothing, at all, that comes ahead of maintaining a proper level of attention to its control and the surroundings you are within. The call will wait until you are not busy with driving, but even if it’s of extreme importance, then pull the fuck over. Texting, it should go without saying, is not only completely unnecessary in virtually all regards, it is the stupidest goddamn thing to risk anyone’s life over. You don’t need to be playing with your My Little Pony action figures either, which rate the same level of importance and usefulness…

Chill the fuck out. Nobody cares if you’re late for something, or don’t like being held up in rush hour traffic, or whatever. If you’re late, it’s your own fault – own it. And traffic is traffic – if you’re in it, you’re part of the problem, aren’t you? But madly switching lanes, cutting people off, and tromping on the accelerator can provide, at best, a fractional improvement in the situation while exponentially increasing the risk. Worse, if you think that any of these things are going to correct the situation, then you’ll just get even more irritated when you inevitably find out that they don’t do shit.

It’s not a competition. I’m not sure how this idea got started, but speeding, especially through town where we all travel between traffic lights, cannot provide more than an immeasurable difference – nobody is doing time trials, Andretti, and your dick isn’t bigger than the guy you have to pass. I know how satisfying it must be to get to the next traffic light ahead of someone else, almost as satisfying as being first on the playground for recess, but nobody is keeping track or actually gives a fuck. I mean, organized sports themselves are pointless and childish, but carrying this idea over onto the road is especially asinine.

Braking isn’t painful. Seriously, it’s not – try it and see. And believe it or not, it’s far safer to do so when approaching stopped cars on the roadside, or bicyclists, or pedestrians. You’re going to get where you were going, in extreme situations, perhaps 45 seconds later than intended, but most often it’s down to ten seconds or less. If your time is that valuable – oh, bullshit, it isn’t, so get over it. Slowing or, god forbid, even stopping to prevent a close encounter or potentially dangerous situation is not going to count against you in any way. Moreover, if the hazard is in your lane, then oncoming traffic actually has the right of way. This means, to spell it out in small words, you wait for them.

Between the lines, all the time, every time. Why do I even have to mention this? The lane markings are there for a reason, and it’s as a guide to prevent, you know, little inconveniences like head-on collisions. Staying within those guides, as opposed to cutting corners or sweeping wide, takes literally an immeasurable amount more effort – you might have to bring the other hand into play and will have to stop playing with yourself, but so be it. If you’re physically unable to remain in the lane, you’re undoubtedly going too damn fast. It’s a really stupid thing, and I have no idea how people justify it to themselves, but I see it a lot. There’s even a thing here where, when a painted divider widens between lanes, people feel this is extra space for them to use in cornering (and even on perfectly straight roads, and try to figure that one out,) never actually realizing that it’s a bad situation if the oncoming driver behaves in exactly the same way.

It’s not a matter of special privilege. We’re all on the same roads, we all have the same importance behind being there, we all have the same frustrations. There’s nothing that makes you special – I’m sorry to be so blunt and direct about it, but you’re old enough to drive, you can handle it now – buck up. There are a lot of drivers, it seems, that rely on everyone else on the road obeying the laws so that they’re free not to. And there are plenty that feel that their presence on the road is somehow more important than everyone else. I know this is hard to believe, but there is no royalty in the US at all, and especially not in North Carolina.

If the traffic light has stopped working, the intersection has become an all-way stop. Seems like simple logic, but there are much simpler people out there, a lot of them. I think they believe that, if there is no red light, then it’s somehow safe to enter an intersection, again, never really fathoming that anyone else believing the exact same thing means lots of mangled metal and pooling blood. It never seems to register that there is no green light – you are not denied permission, you have never received it in the first place.

Turn signals are not an advanced skill set. This is apparently a well-kept secret, but pushing up on that little lever, as fatiguing as that might be, means turning right, while down means left. This applies to all turns, and even lane changes. Again, a reminder about competition and privilege, but it’s actually a good thing to let others know what the fuck you’re about to do, and follows this arcane concept called courtesy. Look it up if you need to. And you might, because a turn signal is not considered permission to cut someone off or change lanes without safe clearance – nothing is, actually. If you need to get out of the lane you’re in, you wait until it is clear and safe to do so. It might take as long as the average YouTube video of someone crashing their skateboard, and we all know how excruciating it is to sit that long – it’s like waiting for the microwave to finish with that damn burrito. Agony!

The laws of physics will make you their little bitch if you need the reminder. No matter how much in control you believe yourself to be, no matter what kind of driver you tell yourself you are, simple physics still rules and couldn’t care less about your ego. The faster a vehicle goes, the more effort it takes to stop, and the more likely it is to break traction. And the more sudden you have to maneuver, the more likely the vehicle is to tell you to go fuck yourself. Truly experienced drivers never believe they are in control, only that there are situations where the chances of losing control are far less than others. Such situations include safe following distances, safe maneuvers, and speed appropriate to conditions.

All bets are off. We are a betting species. We believe, constantly, that while something bad might happen, as long as it doesn’t happen right now, then we are ahead of the game. It’s okay to leave our lane on a blind hill or curve because the chance of an oncoming car coming through right now is low enough to save us the supreme effort of having to slow down. Too many people really do believe that if it hasn’t happened yet, it will continue not to happen. These same people keep buying lottery tickets, so apparently they aren’t consistent in these beliefs, but then again, they’re special, so who cares what physics, experience, or logic tells us?

What’s disturbing about this is, how simple it is to avoid it all. The best technique is usually called defensive driving, but there are probably a lot of sports-minded chuzzlewits out there who don’t like the idea of pussy defense, so it’s better to just call it accepting the risks. At any time, something bad might happen, and believing that is the first step towards handling it. But more importantly, driving a vehicle means having the responsibility of an inherently dangerous mass of metal, one that there is no perfect control over. And when something goes awry, the potential for fatalities is significant – just ask any emergency responder. It’s really, really hard to weigh the likelihood of killing someone, including ourselves, against the horrible inconvenience of driving a bit slower or being a little considerate of those around us. I know, right?

And worse, so much of the irritation with other drivers comes from them behaving exactly like us. Too many people seem to believe that hey, if they aren’t going to drive respectfully and safely, why should I do so? Which is the same as saying, “If they can be stupid, why should I be the smart one?” Funny, I always thought that was kind of the goal in the first place, but if you’re the type to resent being better than the fucktards, well, I know a few that aren’t even allowed to drive, so…

I had another session with the immutable

I had another session with the immutable

There are a few people, it seems, who imagine wildlife photography to be kind of a rough-and-tumble business involving forbidding locales and exposure to challenging and sometimes dangerous encounters with fauna. To those people I only want to say, “You’re absolutely right!” While out capturing the images within this post, I was better than ankle-deep in some muck that could have sucked my sandals clean off, had I not been careful, and there was even a chance of being stung by a bee, perhaps more than once. And there was no one within, oh, about two hundred meters or so. The walk back to the car alone, at the edge of a shopping center parking lot, was a good thirty meters through poorly-cut weeds. Uphill.

There are a few people, it seems, who imagine wildlife photography to be kind of a rough-and-tumble business involving forbidding locales and exposure to challenging and sometimes dangerous encounters with fauna. To those people I only want to say, “You’re absolutely right!” While out capturing the images within this post, I was better than ankle-deep in some muck that could have sucked my sandals clean off, had I not been careful, and there was even a chance of being stung by a bee, perhaps more than once. And there was no one within, oh, about two hundred meters or so. The walk back to the car alone, at the edge of a shopping center parking lot, was a good thirty meters through poorly-cut weeds. Uphill.

A few of those were solicited from Dan Palmer, mostly because I got tired of doing this thankless task. I don’t think he’s very accomplished at being genuinely grouchy, instead more like playacting, but then again, he does have two teenaged daughters, which is something that could be added to the list I guess, if I posted with a bit more advance notice…

A few of those were solicited from Dan Palmer, mostly because I got tired of doing this thankless task. I don’t think he’s very accomplished at being genuinely grouchy, instead more like playacting, but then again, he does have two teenaged daughters, which is something that could be added to the list I guess, if I posted with a bit more advance notice… We are revisiting the photos taken during my

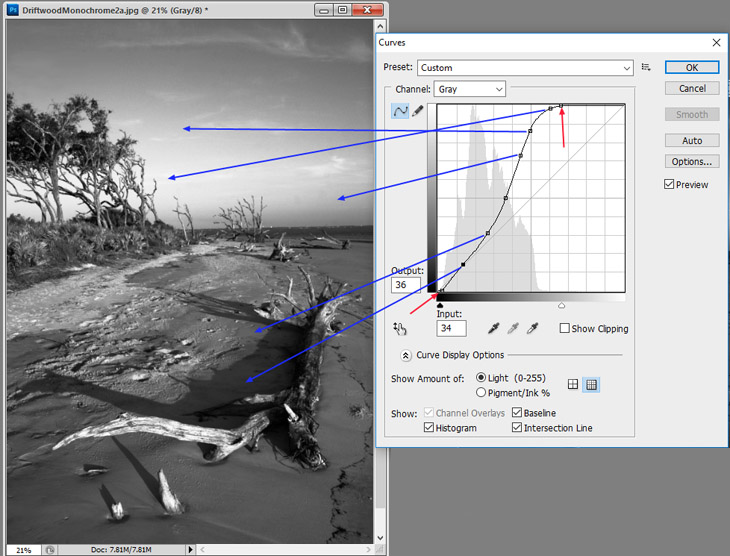

We are revisiting the photos taken during my  Let’s take another look at converting color images into monochrome. It’s not very often that I’m out with the intention of shooting images to be converted, and I never switch the camera over to monochrome mode; instead, during sorting or editing I’ll pick a handful of images that look like they might fit the bill and see what comes up with the conversion and a little tweaking. So in this case, we’ll use one of the shots taken at Driftwood Beach on Jekyll Island, seen at left. Monochrome images make use of contrast above all else, and this image was taken as the rising sun was transitioning from low-contrast light, diffused by the thicker atmosphere at the horizon, to the high-contrast light of bright sun in clear skies – we can see the sharpening contrast in the textures of the rough sand and the trees against the sky. I consider this a moderate level of contrast, not the best candidate for monochrome, but it has promise, especially in the variety of textures. So we’ll start with simply wiping out the color by converting the image to greyscale.

Let’s take another look at converting color images into monochrome. It’s not very often that I’m out with the intention of shooting images to be converted, and I never switch the camera over to monochrome mode; instead, during sorting or editing I’ll pick a handful of images that look like they might fit the bill and see what comes up with the conversion and a little tweaking. So in this case, we’ll use one of the shots taken at Driftwood Beach on Jekyll Island, seen at left. Monochrome images make use of contrast above all else, and this image was taken as the rising sun was transitioning from low-contrast light, diffused by the thicker atmosphere at the horizon, to the high-contrast light of bright sun in clear skies – we can see the sharpening contrast in the textures of the rough sand and the trees against the sky. I consider this a moderate level of contrast, not the best candidate for monochrome, but it has promise, especially in the variety of textures. So we’ll start with simply wiping out the color by converting the image to greyscale.