Today we’re going to talk about something that nearly every modern camera has, some better than others, but also has its faults; specifically, so you know when it might become undependable and when to shut it off.

Autofocus has come a long way since its first application, but it still remains easy to fool in certain circumstances. Let’s begin with a little understanding of it. The most basic property is, it needs a certain amount of light to work – once the view gets too dim, the autofocus sensor within the camera body cannot adequately resolve the contrast that it needs, which is why nearly all lenses available today have a maximum aperture or f5.6 or larger (in some cases, f6.3, which seems to define the limit.) It’s better if the lens has an even larger aperture, which in the seemingly-reversed terminology of lenses/apertures is a smaller number, like f4 or f2.8. Zoom lenses will often be listed as a range of numbers – in the example at right, f3.5 to 4.5 (the “1:” can be replaced with “f” – all of this is explained here.) What this means is, the lens has a maximum aperture of f3.5 at the shortest focal length, one end of its zoom range, and f4.5 at the longest, the opposite end. These are, however, only the maximum apertures, while the lens may reach f22 or f32 throughout its zoom range as a minimum aperture. The reason only the maximum aperture is listed as a basic specification is to show how much light it can admit, and autofocus benefits from this. Autofocus sensors work by adjusting the lens focus until the maximum contrast is achieved.

Autofocus has come a long way since its first application, but it still remains easy to fool in certain circumstances. Let’s begin with a little understanding of it. The most basic property is, it needs a certain amount of light to work – once the view gets too dim, the autofocus sensor within the camera body cannot adequately resolve the contrast that it needs, which is why nearly all lenses available today have a maximum aperture or f5.6 or larger (in some cases, f6.3, which seems to define the limit.) It’s better if the lens has an even larger aperture, which in the seemingly-reversed terminology of lenses/apertures is a smaller number, like f4 or f2.8. Zoom lenses will often be listed as a range of numbers – in the example at right, f3.5 to 4.5 (the “1:” can be replaced with “f” – all of this is explained here.) What this means is, the lens has a maximum aperture of f3.5 at the shortest focal length, one end of its zoom range, and f4.5 at the longest, the opposite end. These are, however, only the maximum apertures, while the lens may reach f22 or f32 throughout its zoom range as a minimum aperture. The reason only the maximum aperture is listed as a basic specification is to show how much light it can admit, and autofocus benefits from this. Autofocus sensors work by adjusting the lens focus until the maximum contrast is achieved.

But what exactly does this mean? Well, sharp focus is actually about contrast between different colors or brightnesses within the image. A sharp image has nice, distinct, and very specific delineations between these contrast areas, while an unfocused image blurs these distinctions and the contrast becomes a gradient, muddy and indistinct. The only thing autofocus does is adjust the lens focus until this contrast is as high as possible – within the sensor’s active area, of course.

But what exactly does this mean? Well, sharp focus is actually about contrast between different colors or brightnesses within the image. A sharp image has nice, distinct, and very specific delineations between these contrast areas, while an unfocused image blurs these distinctions and the contrast becomes a gradient, muddy and indistinct. The only thing autofocus does is adjust the lens focus until this contrast is as high as possible – within the sensor’s active area, of course.

[Caveat: Some Nikon cameras have a ‘phase-detection’ autofocus that instead relies on two microlenses with some separation between them working together in a form of depth perception, or old rangefinder focus aids if you’re familiar with those. I have not had the opportunity to use this at all, much less at length, so I can only go on the claim that this is supposed to be faster and more reliable than contrast detection, though I imagine some of the situations below would still provoke issues or failure to focus.]

Too little light, however, means that the sensor cannot distinguish the contrast well enough, and may ‘search’ by continuing to focus the lens in and out, or may select the nearest region with contrast that it can detect, or it may simply balk and not do anything. This is why lenses with those larger apertures (smaller f-numbers) are more sought after, because they let in more light and allow better focusing (even manually.) Even then, it doesn’t always work.

[Note, too, that the lens remains at maximum aperture for the focal length in use, regardless of the aperture setting chosen by the photographer, until the shutter is tripped, in which case it closes down to the chosen setting in milliseconds right before the shutter opens. This way, the autofocus and the viewfinder receive the maximum amount of light to focus. This has the added benefit of maintaining the shortest depth-of-field until then as well, making it easier to know when focus is on the correct spot.]

So too little light will prevent autofocus from operating effectively – and so will too little contrast at the chosen focus point. Should a subject have only subtle contrast or color variations, or blend in too well with the background or foreground, the autofocus can easily get balky. Autofocus assist lights exist on many cameras and some flash units, and these add light as needed, often in infra-red so the light isn’t noticeable, but you’ve likely seen how your smutphone will use illumination to focus and can even see it in action on the phone screen. However, these lights usually have a very limited range – a few meters at most – and can still be thwarted by a low-contrast subject. The solution to this, fairly often, is to look around in the immediate vicinity to see if something the same distance away has better contrast and use that to lock focus onto, then re-frame the shot and trip the shutter.

Autofocus can have several different settings, however, and any photographer doing action shots of any kind usually selects a mode that means the autofocus will attempt to keep up with the action – this means that picking another subject, or portion thereof, and trying to reframe will simply cause the camera to change focus as it detects this ‘action.’ Changing autofocus modes can help, but might cause a precious delay when trying to get the shot.

There are also cases where a subject is very small in the viewfinder and moving too much to keep well centered within the AF area, and so the autofocus then tries to grab something else with adequate contrast; this happens a lot in my field when tracking a bird in the air and it crosses the horizon line, which is larger and features more contrast.

One solution, which is active on my camera bodies, is to assign a particular button on the body to stopping autofocus – Canon, at least, allows this to be set on most bodies that have an AF button near your right thumb. Once focus is achieved (and the subject is not changing distance from the camera too rapidly,) holding down this button stops autofocus entirely while it is held, preventing focus searching. Naturally, this only works if focus is adequately sharp when the button is pressed.

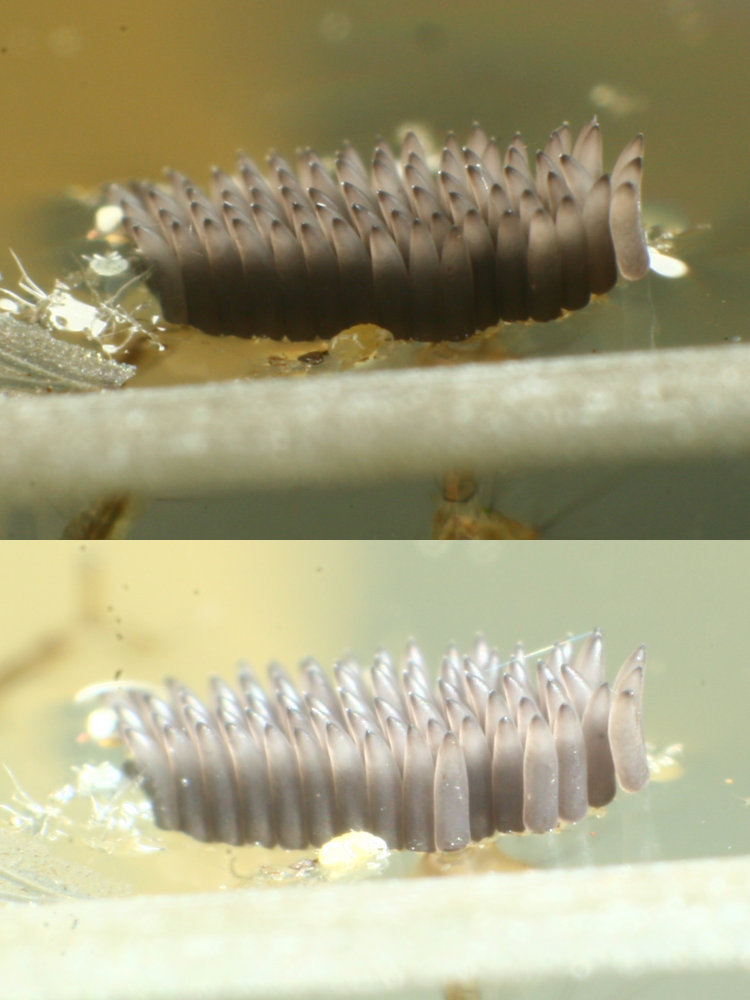

As mentioned, a very small subject can cause autofocus to ‘get confused,’ since its sensor area might be receiving contrast from the subject or its surroundings, especially with handheld cameras that can twitch a little too much while aiming (magnified several times over with longer focal lengths.)

What to do about these? Well, there are several options, though none that will handle or be useful for every situation. One of the first is, if there is a focus limiter on your lens, this can help prevent the long focus search when AF can’t lock on, racking all the way out to ‘infinity’ and back down to closest focus, during which you may lose sight of your subject entirely and even lose it out of the frame. This is most useful with long focal lengths, and such a limiter switch is found more often on those.

An appropriate AF mode for your subject matter helps a lot, as well as knowing how to switch them quickly. Most cameras have a ‘Single Shot’ mode where the lens will autofocus only once until it locks onto a particular distance/subject, and will hold this until the shutter is tripped; in order to get it to re-focus, the shutter button must be released (lift your finger) and repressed. Then there are different forms of active or tracking autofocus, intended for moving subjects, where the camera attempts to predict where to keep adjusting based on the previous movements. Certainly, some of these are better than others depending on what kind of subjects you pursue, but none that I have ever tried are free from issues and just plain inability to focus.

One of the more distinctive options that you should be prepared to exercise, at any given time, is simply turning the autofocus off. When the camera is doing nothing but focus hunting without ever locking on, or when you’re not particularly sure the focus actually locked onto what you intended, or if the key focus point is very small and distinctly different from the surrounding area (this happens a lot with macro work,) just turn it off. For this reason, I encourage everyone to know where the AF switch is on their lenses or bodies, and be able to find this by feel without even looking; lens manufacturers don’t exactly help this by being inconsistent with where the switches are on the lenses, or not making them distinctive enough to locate dependably by feel (much less switch on and off with gloves on, for instance.) But when you need it, you need it, and it should be considered a viable option the moment you can’t achieve autofocus.

For this to work, however, you need to be able to see clearly in the viewfinder. Most cameras have a diopter dial on the side of the viewfinder window, and you use this to adjust the viewfinder view until its the sharpest that it can be to you. The best way to do this is to use autofocus to lock onto an easy subject with very distinct contrast and sharp lines, preferably on a tripod, and then adjust the diopter dial until the view is sharpest. And be aware that it’s still possible to bump this damn dial and fudge your setting, which you may not realize until its crucial.

There’s also the idea of focus bracketing, which means, taking several frames while making fine adjustments to the manual focus in between; I use this all the time when doing sun or moon shots, to ensure that focus is as tight as possible (it does not help that the Tamron 150-600 that I’m using for such shots has a very twitchy focus ring, where infinitesimal tweaks can have more radical affects than they should.) Some cameras even have this as an option, while many lenses allow you to tweak focus manually even while set for autofocus, which can be handy for pinning down that tricky subject, as long as the lens does not keep competing with you to select something else as soon as you’ve pinned down the focus that you want.

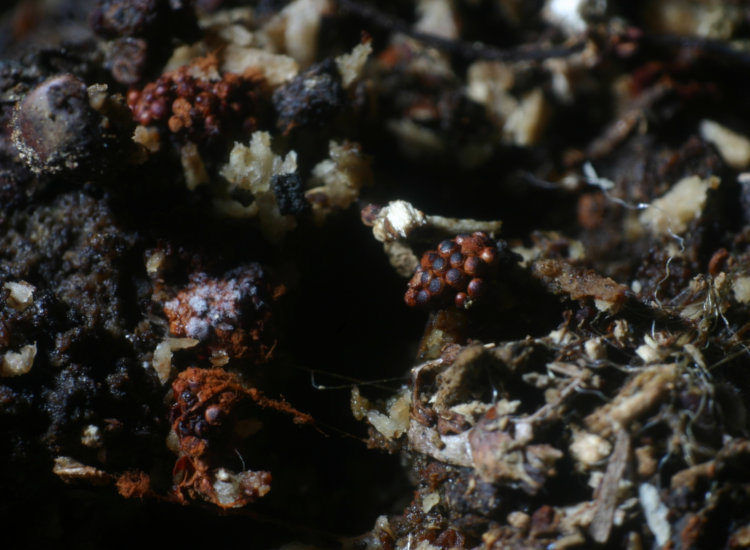

A small variation of this technique with macro work is to switch to manual, get close to the ideal focus, and then move the camera until the focus is perfectly sharp, which really only works with the very short depth-of-field that macro magnifications provide. This is fine with tripod work, especially with a macro slider that allows very fine adjustments to distance, but it’s a lot trickier handheld; nonetheless, I do this quite often, solely from the convenience of getting the shot immediately, but I also fire off several frames to try to ensure that at least one of them is bang-on.

A smaller aperture to increase depth-of-field can help reduce or eradicate those situations where focus wasn’t quite as precise as intended, though this is not something to rely on – a high depth of field reduces how quickly or noticeably something goes out of focus, but if the image is not focused properly, it can still be visible.

And while we’re on the subject of macro work, any method where you can increase the amount of light to focus with can help a significant amount, which is why I do ‘macro studio’ work on a desktop with bright LED lamps, even when the image lighting is provided by a flash unit, and will use auxiliary focus lighting in the field wherever possible.

On occasion, you may find that autofocus just doesn’t seem to want to work correctly, regardless of the conditions; personally, I’ve found that either poor contacts between the camera and lens, or an unclean focusing mirror are the most common culprits, and I’ve addressed these in detail in this post. Since then, I’ve also stumbled upon the discovery that poor contact with the camera battery occasionally throws some balkiness, usually fixed by either reseating the battery or by cleaning the contacts on that.

Hopefully you’ve found something herein that will help improve your autofocus performance or results. Once again, good luck with it!

S’okay, granted, we got a bit more snow this time, but that really is my tea mug in there – somewhere. The faint breeze wasn’t allowing for a nice vertical vapor trail and I was timing it for when it swirls became visible against the darker background trees. I also hadn’t planned on doing an animation so the camera wasn’t remaining in exact position, and thus the background dances a little (mostly because I aligned the snowpack together for the four frames.) Should have thought of it earlier when the sun was lower, but here we are, feeling the enormous regrets of life. And reheating my tea…

S’okay, granted, we got a bit more snow this time, but that really is my tea mug in there – somewhere. The faint breeze wasn’t allowing for a nice vertical vapor trail and I was timing it for when it swirls became visible against the darker background trees. I also hadn’t planned on doing an animation so the camera wasn’t remaining in exact position, and thus the background dances a little (mostly because I aligned the snowpack together for the four frames.) Should have thought of it earlier when the sun was lower, but here we are, feeling the enormous regrets of life. And reheating my tea…

Bear in mind that this is not just two successive frames, but two successive drops, captured after falling almost the exact same distance – we’re talking just a couple of millimeters difference. But keep staring at it, because those background trees will start your eyes twitching.

Bear in mind that this is not just two successive frames, but two successive drops, captured after falling almost the exact same distance – we’re talking just a couple of millimeters difference. But keep staring at it, because those background trees will start your eyes twitching.

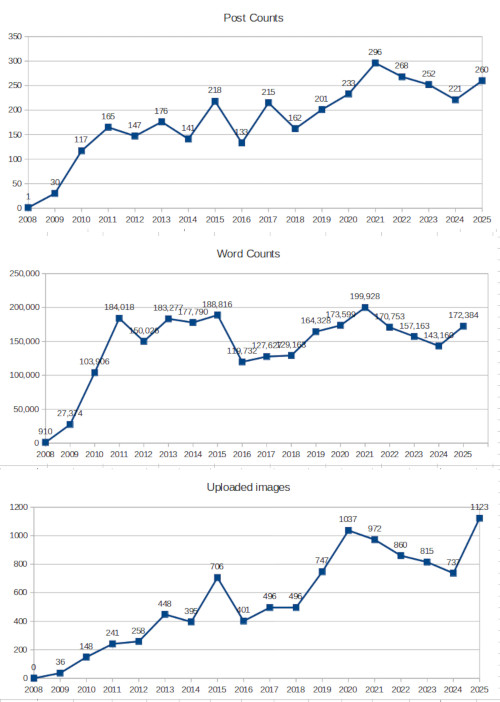

We brought the site stats up much, much better in 2025, with a post count of 260 (coming in third behind 2021 and 2022,) and a word count of 172,384, about average, bringing the total for the life of the blog up to 2,573,954.

We brought the site stats up much, much better in 2025, with a post count of 260 (coming in third behind 2021 and 2022,) and a word count of 172,384, about average, bringing the total for the life of the blog up to 2,573,954.